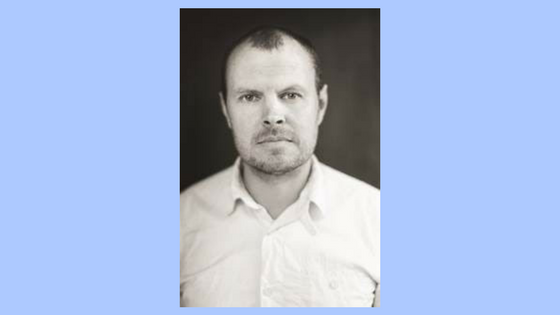

Phil Harrison on Finding the Joy in the Darkness of his New Novel

Phil Harrison’s novel The First Day spans decades in tracing the fallout caused by a tumultuous love affair in Belfast. When Beckett scholar Anna meets local pastor Orr in 2012, they embark on a passionate relationship despite their profound differences, thus permanently altering their families’ lives. Thirty years later, their son Sam must deal with the aftershocks of their relationship as he navigates his carefully isolated life in New York City. Publishers Weekly noted “Harrison’s remarkable writing elevates a story that is all the more powerful for its eschewing of easy answers and resolution,” while Kirkus raved that “Harrison’s elegant prose and deeply felt characters create a novel with a fiercely beating heart.” Harrison spoke to Brendan Dowling via email on November 6th, 2017.

You come to writing from the world of filmmaking. Did you bring any of the skills you learned in telling a story cinematically to how you told the story of Orr and his family?

Writing screenplays has definitely informed my prose—I am much more interested in having characters do things than in telling people what they are like, which you have to do in cinema. But the question of voice—who is speaking and to whom, and what are they not saying, etc.—all of these are more interesting questions in a novel, and afford a writer more space to play with (and rope to hang himself).

When we first meet Orr, it’s in 2012 Belfast and he’s about to embark on an affair that pits his faith against his desire. The setting is so specific—is there something about Belfast where this story could only have taken place there during that particular time?

There is undoubtedly a strong, problematic evangelical religious tradition in Northern Ireland. There are many men who—if not like Orr exactly—nonetheless engage their faith with the kind of visceral, unwavering commitment. And Belfast right now inhabits an in between space—the troubles of the recent past abandoned but the future as yet very much open. I have no doubt that similar affairs must be embarked on in lots of places—but my own interest in and commitment to Belfast (and my history here) made it a natural setting for me.

The setting of the second half of the novel takes place roughly thirty years in the future in New York, where we follow the life of Orr and Anna’s son, Sam. Even though this part is set in the 2040s, it has a certain out-of-time quality, with none of the typical signifiers to show us how the world has changed. What appealed to you about writing about the future in this almost timeless way?

This idea came during the process; I hadn’t intended to do this from the start. It’s partly an exploration of what theologians call teleology—the idea that history is moving in a direction, following a line. “The arc of the universe bends towards justice” said Martin Luther King Jr, which is a lovely sentiment but ultimately bullshit. There is no inevitability—one thing follows another, and then another, and then another. I think whatever meaning we want must be made by ourselves—created—rather than inherited. The playing with the future, without creating a ‘futuristic’ novel—is a small formal approach to reminding us that the question is a live one.

Anna is a Beckett scholar, and his words impact many of the characters throughout the novel. How has Beckett been influential to you as a writer?

It seems to me people tend to fall into one of three approaches to life and meaning: repressed (there is a meaning and I must find it—God, nationalism, whatever); tragic (there is no meaning and that’s fucking awful); or comic (there is no meaning—haha, let’s go make some). I learned a lot from Beckett about the last two, but especially the latter—the necessity of finding joy, or even just humour, in darkness. The novel feels to me less about finding meaning than making it, or perhaps finding that you need to make it.

One of the many intriguing aspects of the novel is discovering the identity of the narrator. Without giving anything away, can you talk about how you arrived at telling the story through this person’s point of view? What were you able to explore through a first person narrator that you couldn’t accomplish through an omniscient one?

I’m naturally sceptical of omniscient creators—I’m unfortunately too modern to not be—but I’m also sceptical of writers wanting to impress us with how they know this, constantly reminding us of it. So I needed to find a voice that was sufficiently limited, but also wide enough, compelling enough, truthful enough to tell the story convincingly. And of course, the narrator’s limitations, as the novel progresses, become more important, more revealing.

At the end of the book, one of the character’s comments on his inability to “step fully into [his] life,” which seems like a struggle many of the characters in the book face. What draws you to these characters who, for whatever reason, can’t get out of their own way?

That’s a great way of putting it. I’ve never met anyone who absolutely avoids getting in their own way—if there’s a definition of the human animal as opposed to other animals, it must be that we are the self wrecking creatures, but also the creatures who can laugh at this, explore this. And of course the two must be connected. I’m endlessly fascinated by our capacity to frustrate our own desire, and to hand over authority to people or ideas that will ultimately demean us. And that spatial metaphor—imagine ‘stepping into your own life’, implies a space which is at our disposal, which is available to us, but which we are somehow incapable of occupying. And both the space, and the ways we close it down—or permit or even force others to close it down—this is the relentless human drama.

And finally, what role has the library played in your life?

When I was a kid I would go to the library every week and stock up on books—often, in the early days, Tintin and Asterix comics, then the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. The books have changed—for the most part—but the appetite for reading I developed then has never disappeared. Reading is still a vital, vibrant part of my everyday. I don’t know who I’d be without it.

Tags: author interviews, authors, Phil Harrison