The E-Book Experiment

The proliferation of e-books over the last ten years has been nothing short of staggering––sales of e-books in the United States last year more than doubled to $441.3 million from $169.5 million, according to the Association of American Publishers.1 The share of adults in the United States who own an e-book reader doubled to 12 percent in May 2011, up from 6 percent in November 2010.2 This may well indicate a kind of tipping point not only in where publishing is headed, but in what our patrons will want from us.

This growth in popularity and demand for e-books presents many challenges to public libraries. At this point, the way most people access e-books completely bypasses the library. The options that libraries have today for e-books (in terms of content, interface, interoperability, and so on) are very limited, and that greatly impacts the primary role of the library––to connect people and information.

E-Books: Problems, Challenges, and Opportunities

E-books seem to present challenges that go against the core mission of libraries. The move from print to digital, along with the shifting business model from content ownership to content licensing, are some of the largest challenges facing libraries today. Electronic books are not always owned when purchased by libraries. Instead, materials are only leased for a certain period of time, and in some cases are not available to libraries at all. The current environment allows publishers and aggregators to control our content, in ways they can’t with our print collections.

In addition, getting an e-book from a library can be a confusing process; so much so that library staffers wind up creating elaborate tutorials on how to borrow an e-book. Simple downloading processes with retail outlets like Amazon provide readers with access to vast collections of e-books and pose serious competition for libraries.

What Do Libraries Own and What Does That Mean?

When Douglas County (Colo.) Libraries (DCL) buys physical books, we own those books. They don’t disappear unless we choose to remove them from the collection or a patron loses them, in which case we usually recoup our costs in patron fees and fines. We can loan those books through other library systems and we can put them on hold, incurring no costs for that book beyond the initial purchase. With e-books, we pay hundreds of thousands of dollars

to license books from a vendor––but we do not own anything. If we were to cancel our subscription, those books would be gone. We also do not have archival rights to the books we have paid for, even if a vendor goes out of business. The vendor also has the power to add or delete books from our collection depending on their current deals with publishers. What are libraries to do when a book is taken out of its print form and only exists as an e-book?

The Squeeze on ILL

Interlibrary loan (ILL) is another area that is affected by the growing demand for e-books. ILL is an important part of what we do in libraries. As we turn our efforts to respond to patron demand and begin buying more e-books, and with only a small number of e-book vendors (mostly academic) allowing for any sort of ILL, the more our book collections go digital, the less we will be able to loan to other libraries or borrow from other libraries.

Too Many Platforms, Too Little Interoperability = Limited Discovery

Libraries want to provide e-books through a single, easy-to-use, easy-to-search platform. Unfortunately, that may never happen. Vendors continue to create their own distinct platforms: OverDrive, Baker & Taylor, Simon & Schuster, 3M, ProQuest, EBSCO, etc. Libraries are expected to present all of these platforms to patrons in a way that makes sense, which is near impossible.

Library catalogs have been the primary resource patrons use to browse and locate materials. The library catalog is perhaps the best single place to make our e-book collections discoverable, but many catalogs lack the sophisticated search functionality of the individual vendor platforms themselves. The solution then lies in the integration of these platforms for discovery and delivery.

Browsing is still an important part of the discovery experience, but serendipitous browsing is not replicated well online because libraries offer a mix of vendor e-book collections and traditional print books. Add to the mix the nightmare of ensuring that your library’s e-books work on the plethora of mobile devices and e-readers patrons will tote into the library.

When it comes to technology and e-books, it is very difficult for a library to make decisions or plan ahead, due to the number of e-reader devices (Kindle, iPad, Nook, etc.), and the number of e-book formats (EPUB, PDF, Flash, etc.). A single standard for e-books would ease maintenance and administrative burdens. Libraries should be cognizant of the issues (business, technical, and legal) so that we make the best possible decisions and lobby for better interfaces. There is no legitimate reason why any book in the library should be encumbered by digital rights management (DRM).

Libraries have historically been too complacent to negotiate directly with publishers, to create consortia to lend e-books, to fight DRM, to create our own lending/license conditions, to promote an e-reader model, to produce any technology such as a basic desktop e-reader, or even to demand open formats. If all libraries had supported one format and bought a particular e-reader ten years ago, imagine the power we would have. DCL made the decision not to wait any longer––as no one is really sure what the future for e-books holds.

DCL believes that no contract should be signed without the right to own a copy of the e-book file, to lend that e-book to our users for as long as we decide, and to receive the e-book in an EPUB format. The library profession must do its best to push publishers to come up with better platforms and purchasing/licensing options. We should fight to regain control of the content and establish our own rules––rules that will benefit the library patron the most.

The DCL Experiment

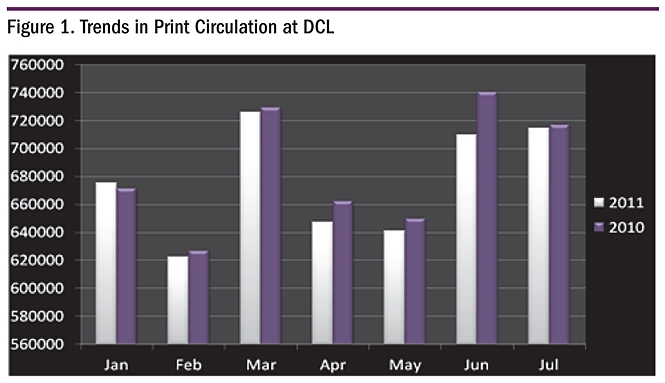

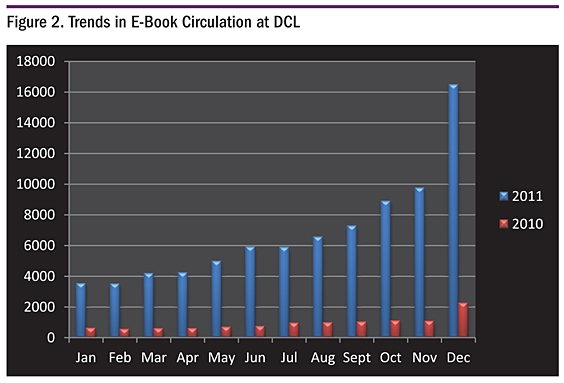

DCL, located just south of Denver, serves a population of close to 300,000. As the third largest library district in the state, it features seven libraries and is considered one of the busiest libraries in the United States, with more than eight million items checked out annually. However, for the first time in over two decades, DCL is actually seeing a decline in circulation growth in almost all categories––with the exception of digital downloads (see figures 1 and 2).

DCL has been very innovative in its current experiments with e-books. We are leveraging the e-book opportunity to improve service and reach more users than ever before. Our immediate goals to improve the library e-book user experience include:

- to enhance the discovery of e-books with VuFind library catalog software;

- to simplify the delivery and circulation of e-books with Adobe Content Server (ACS); and

- to challenge a business model based on content license, with one based on content purchase.

Library staff have developed software to optimize the e-book user experience; implemented Adobe Content Server to store and deliver e-books that require DRM; and begun working with publishers to develop an e-book purchase model that will fairly compensate writers and publishers, while meeting the expectations of library users.

The Software

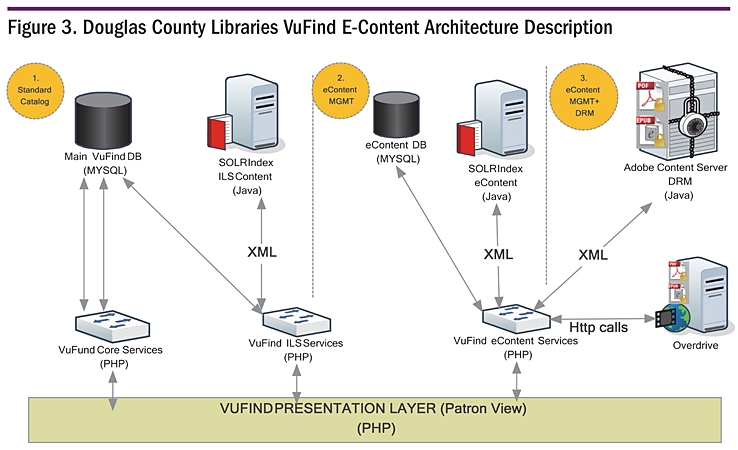

The software components of our system include (see figure 3):

- ACS, which primarily handles DRM;

- VuFind––an open source discovery layer that interfaces with our integrated library system (ILS) to allow patrons to easily find titles they are most interested in. The base VuFind code has been heavily modified to handle e-content management. Many application programming interfaces have also been added to VuFind to enable additional products to be created on top of the VuFind platform such as our powerwall displays;

- an Android and IOS e-reader/mobile app; and

- an engine that provides Amazon-like recommendations.

The e-content delivery platform:

- handles the management of e-content with both unlimited usage and e- restricted usage;

- allows e-content to be viewed online from a DCL-developed, cloud-based HTML5 reading system in the browser application;

- allows e-content to be downloaded for offline usage;

- allows new e-content to be purchased;

- allows e-content to be searched so patrons can easily find titles that are of interest to them;

- includes various reports to help collection development staff purchase titles that are of interest to their patrons and weed titles that are no longer used; and

- handles the management of holds and checkouts for e-content to eliminate the need to manage the items within the library’s ILS.

The beauty of our system lies in the fact that the number of steps from search and discovery to checkout has been greatly streamlined to no more than three clicks.

Future developments include:

- a content acquisition and aggregation system for selection and purchasing;

- replicating the system to other libraries. We are currently set up to pilot with the MARMOT Library Consortia in the western slopes of Colorado;

- a publishing platform that will set up the library as publisher for any self-published authors––crowd-sourcing; and

- incorporating other content types other than EPUB and PDF (video, audio, and so on).

The Display

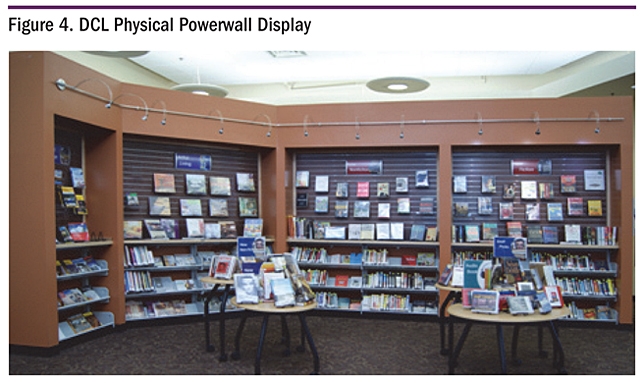

Circulation of print materials at DCL is high because we purchase, manage, and physically display our collections in a smart, appealing, and engaging way, through the use of our powerwalls (see figure 4). Powerwalls are located almost immediately as you enter the library, giving the patron a true retail experience featuring popular material. From research, we know we have only thirty seconds to catch a customer’s attention and keep him or her engaged. People come to the library to browse––to use their eyes and bodies to explore. Our powerwalls are successful because they meet consumers’ needs and interests the minute they enter the library. We know powerwalls work, because at least 60 percent of our circulation is driven by these displays. We decided to apply this same model to e-books in order to create a successful virtual browsing experience.

DCL now offers virtual solutions that allow patrons to explore digital material. Our new touch screen displays (two to three 52-inch digital touchscreen displays), are located adjacent to our physical powerwalls, and feature e-book content for easy browsing and downloading. We also have an online e-book storefront within our online catalog, as well as a mobile app, that allows us to display the same dynamic content.

Browsing is a key feature of the digital discovery experience. Our virtual powerwall displays staff-selected e-content using the same principles that drive our physical displays––what people look for, what’s hot, or what’s seasonal. What we are after is to manage this content as intelligently and professionally as we do our other collections.

The Publishers

Lastly and most importantly, we’ve established agreements with publishers to allow DCL to purchase and manage the digital rights for e-books.

To date, we’ve secured agreements with Lerner Digital, the Colorado Independent Publishers Association, Marshall Cavendish, ABDO Publishing Group, Independent Publishers Group, Dzanc, Book Brewer, and Gale, a leading publisher of research and reference resources for libraries, schools, and businesses

and part of Cengage Learning. Our agreement with Gale includes titles available through Gale Virtual Reference Library, including numerous business titles, travel series titles, and children’s nonfiction titles.

By directly pursuing these agreements with publishers, we emphasize our role as protectors of intellectual freedom and major players in the book-buying industry. After all, public libraries account for a healthy chunk of all book sales, and can properly guard against copying.

Patrons enjoy being able to experience products in new and creative ways that are highly entertaining and exclusive. We recognize that the greatest commercial value for e-books is not the book itself, but the conversations around and through the book. Libraries can position themselves as the vehicles that enable these conversations, and use this to gain leverage with publishers.

The Rollout

Our experiment gets put to the test this winter. We have created our own software, and combined elements––our catalog, ACS, the Vufind “discovery” tool, and a new recommendation engine. All of which have never been combined before.Now we are ready for one more ingredient––our patrons.

Many more reports and articles will follow as we continue to drive traffic, create awareness of our electronic collections, and enhance our customers’ experience with digital content. DCL is proud to bring such a distinct look and feel to our library that is both captivating and entertaining, while still providing a tight and seamless integration into our library system.

REFERENCES

- Matt Townsend, “Barnes & Noble Sinks Most Since June After Halting Dividend,” Bloomberg.com, Feb. 22, 2011, accessed Sept. 21, 2011.

- Kristen Purcell, “E-Reader Ownership Doubles in Six Months,” Pew Internet & American Life Project, June 27, 2011, accessed Sept. 21, 2011.

Tags: e-books