It’s No Joke: Comics and Collection Development

Adult comic book and graphic novel readers comprise one of the most underrepresented groups of readers by libraries today.The inclusion of comic books and graphic novels in libraries is a fairly new concept despite the fact that the first comic book was published in 1934. Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale brought the graphic novel to the attention of libraries in 1986. Maus signifies the point in the history of comics when it became acceptable to include them in a library collection (by some libraries) and questions surrounding their inclusion and classification still exist today. Prior to Maus, librarians never admitted to reading comics since “comics did not belong in libraries because they were not real books and nobody with intellectual sense (that is, the library’s perceived user) reads them anyway.”1 Today, many librarians do not hesitate to say “yes, comics should be in libraries.” After all, “librarians respect information in all formats, functions, and types.”2 Stegall-Armour surveyed twelve librarians at the Lee County (Miss.) Library. Ten of the librarians agreed that graphic novels and comic books should be considered literature while two were undecided. Despite the two undecided, it is important to note that no one said no.

Who are the adult readers of graphic novels and why are they important? Very little demographic data pertaining to graphic novel readers and purchasers has been gathered. It is a great mystery and much of the “data” available is implied. Most data has come from the observations of others and not from thorough survey methods. Based on their experiences with patrons, Lee County librarians agree that graphic novel readers can be placed into five demographic groups: (1) children, (2) teen males, (3) teen females, (4) adult males, and (5) adult females.3 Adult females account for the lowest interest among the five groups, while the other four groups have comparable readership levels, each four times the amount of adult female readers. In 2003, Diamond Distributors, the company that distributes all comic books from all publishers, found that the average graphic novel reader was twenty-nine years old.4 Ryan Searles, graphic novel enthusiast, estimates that in 2012 that number is still relatively accurate, with most graphic novel readers and purchasers being between the ages of twenty-five and forty.5

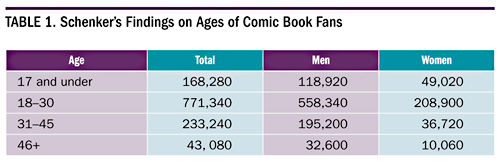

On his blog, Graphic Policy, blogger Brett Schenker used the social networking website Facebook as a way to estimate the ages and genders of comic book fans. He did not disclose his exact method but he took nine fundamental elements from the comic book universe and looked at the demographic information of those who “liked” them in the United States. The total population looked at was 1,215,960 self-identifying comic book fans. Of the users who listed their gender (1,209,800), approximately 75 percent identified as male and 25 percent identified as female.6 Schenker’s findings on ages of comic book fans are in table 1.

He found that eighteen to thirty is the prominent age range for both males and females with male readership dominating each age group. While I believe that this group is the most prominent, it is also important to note that teenagers and tweens frequently lie about their ages (with the help of their parents) in order to use Facebook.7 Therefore, the eighteen to thirty number is likely inflated and the seventeen and under demographic is underrepresented due to this inflation.

Sarah Ziolkowski and Vivian Howard surveyed nine adult graphic novel readers in their study “The Value of Comic Books to Adult Readers.” Of the nine, only three were female. Five of the nine participants were either in the process of completing or already completed graduate-level studies. All participants were employed at the time of the survey. The average age that the participants started reading comics was 8.5 years, with 5 of the 9 having started reading comic books between the ages of 4 and 7 years. All three female readers stated that Manga of some kind (Japanese comics) was their preferred comic book genre. Three of the males reported superhero comics as their favorite genre while two did not provide a favorite genre and one indicated that romance comics were his preferred genre.8

Even with all of the information above, do librarians really know who comes to the library to check out their comics and graphic novels? The honest answer is no. What librarians do know is that comic and graphic novel readers are dedicated to their hobby. The demand for graphic novels in general has increased tremendously over the past twenty-five years––the last five in particular––among all age groups due to the influx of wildly successful films centered on prominent comic book characters. Recent summer blockbusters like The Avengers and its earlier lead-ins such as Iron Man, Thor, and Captain America, as well as the darker films Batman Begins and its sequel, The Dark Knight, have contributed to the increased demand for graphic novels by adults. According to The Comic Chronicles, whose in-depth numbers come directly from Diamond Distributors, Diamond Distributors sold 7.03 million copies in June of 2012. That figure is up 17 percent from June of 2011.9 Graphic novel and comic sales are rising considerably each and every month but a barrier to personal access is today’s cost. Libraries must fill that void and provide access to readers that the depth of their pockets and wallets cannot facilitate.

Today, a comic book reader cannot read just one series of books. Individual comic books such as those based on The Joker and Catwoman will tie into a bigger universe-spanning annual event. To be up to speed on one’s chosen comic book universe (for example Marvel or DC), one must not only read his favorite characters, but there will also be crossover of characters into other books with events leading up to the universe-spanning event.10 Searles indicated that at his most dedicated, he had twenty-five issues in his monthly pick list at his local comic book shop. With individual monthly books costing more than four dollars per book, it could realistically cost one reader one hundred dollars per month to keep up with his chosen universe (if he only chooses one). Add trade collections to that and it is not hard for a comic book fan to spend several thousands of dollars annually on his hobby. However, many readers forgo reading the monthly books and choose to wait for issues to be collected and published in the trade volumes.

Jeremiah Cochran, lifelong comic book fan, estimates that his annual spending on comics is around $300. That figure depends on yearly events, release of trades, and new books written by authors that he has to read. If Cochran could afford it, he could see himself easily spending more than $1,000 per annum on hardcover omnibuses, indie titles, and variant covers (a single issue comic book with the same content but different covers varying in price and rarity). If money were not a concern, he would likely spend $10,000 a year. That includes going after hard-to-find back issues that can be pricey, every title from major publishers like Marvel and DC but also a large majority of titles from Image, IDW, Dark Horse, and Zenoscope. Only titles that he has “zero interest in would remain on the shelf and that list would be surprisingly short.”11

Cochran is not the only comic book fan whose hobby is limited by his income. With cost as a barrier, it is important for libraries to provide this user group of graphic novel readers with what they are looking for. Diamond Distributors Vice President of Sales, Kuo-Yu Liang, stated in 2009 that 10 percent of comic and graphic novel sales go into the public library market.12 Including graphic novels in the library collection increases circulation and use in the library. Studies have shown that patrons who check out graphic novels will come back, not only to read more graphic novels but to read other books as well. Circulation can increase two to four times when graphic novels are added to the collection.13 If this is the case, then why such resistance to inclusion in the collection? While most librarians understand the benefits of housing graphic novels in the collection, the bigger question is where do graphic novels and comic books fit in a library collection?

In addition to a lack of materials available to some users in many library systems, another concern for this user group is the lack of library classification for graphic novels. In Library of Congress classification, all graphic novels are in the call number area PS or NC and those that use Dewey classification, place all graphic novels in the call number 741.5. Graphic novels are not sorted by author, publisher, character, or in any way that is appealing to the user or makes them easy to find. The inability to classify comics and graphic novels in a logical and visible way affects the way that users access this information. If a reader cannot find the few items that he is looking for in three out of four trips to the library, will he come back? Searles has expressed his grief over the classification system utilized by the Cleveland Public Library main branch, which stores its collection in three unique spots. Graphic novels can be found in the popular library, literature, and young adult sections. If one is looking for an entire series and a search of the catalog indicates that all are available, it is very likely that one will have to visit all three locations in order to find all the books. On top of that, they may be organized by author in one section and by character in the next section that is five feet away.

Considering the amount of foot traffic and circulation of materials that graphic novel and comic readers provide, it is still difficult for them to obtain their materials. Whether this is due to the naivety of library staff of the materials’ function and readership or the classification within the library, libraries must make it easier for these users to access their materials. Suggested methods for improvement include the development of a formal and in-depth classification system, the maintenance of an online comic database, programming for readers of comics and graphic novels, close monitoring of the titles that circulate in order to pre-order future titles, and a general interest by library staff to service this subsection of the public.

Searles has considered asking his local library if he can rearrange the graphic novel collection pro bono. Perhaps at one time it was an organized collection that has now lost its way. Nine times out of ten, he cannot find what he is looking for. Libraries have to come up with a universal and encompassing classification system. Some libraries are at odds with graphic novel classification because they don’t know how to classify it. It seems that librarians try to get into the head of the user without consulting the user himself. Will the user be looking for a book by its publisher such as Marvel or DC? Or will the user be looking for a book about a character such as The Incredible Hulk or Buffy the Vampire Slayer? Will the user be interested in a book because of the author? How about the artist? There are so many elements that play into the classification of comics and graphic novels. Searles has proposed a straightforward classification system that puts the items listed above into practice.

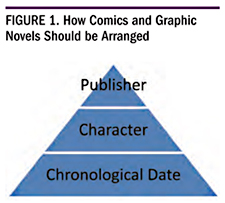

Items should first and foremost be classified by publisher (see figure 1). Comic book readers first have a favorite or a few favorite publishers that they enjoy. An example of a prominent publisher is Marvel Comics. Marvel Comics then has a collection of characters to choose from. Readers of Marvel Comics will find themselves enjoying a particular character or group of characters more than others, so within the classification by publisher, there should be a breakdown by character. A reader who is interested in The Fantastic Four will expect that all Fantastic Four books be together. Within that group of books pertaining to The Fantastic Four, the books need to be rearranged chronologically where they fit in the universe. A story arc from 1988 should come before a story arc from 2009. Searles says that comic books do not need to be arranged by author. “Comic book fans are the most informed group of readers. If a reader is aware of the story arc, he is aware of the author. If the books are arranged chronologically, there is no need to organize by author.”14 This model has been adopted by comic shops for decades and it works incredibly well. Carol & John’s comic shop in Cleveland, Ohio, follows this very method. Searles can walk into Carol & John’s and walk directly to the book he needs without thinking about it. While this may be huge undertaking for a library with a sizeable graphic novel collection, this layout will make access to desired library materials much easier for this user group.

In addition to a more user-friendly classification system, it is recommended that some sort of online comic database be developed for use by patrons with e-readers or via a login system from an in-library or remote computer. Readers of comic books and graphic novels can be considered to be nerds and everyone has heard the term “computer nerd.” It only seems natural to pair comics and computers or other emerging technologies. Graphic novel readers are, at this point, the only group of readers excluded from the e-book craze. Publishers are truly missing out by leaving comic readers as an untapped audience. Examination of the e-book collections of the Cleveland Public Library, Cuyahoga County Public Library, and Columbus Metropolitan Library show that comic-related e-books are limited to biographies of artists and writers, books based on film adaptations, or books targeted toward young readers. While this integration would require compliance on the part of Diamond Distributors, this could increase the library share of Diamond revenue, and open up a library’s collection to a brand new set of readers. This includes readers who cannot find physical copies of what they are looking for (popular items that are always on hold or checked out) or individuals who have denounced the concept of the book in the traditional sense (less common among comic book readers).

It is also recommended that libraries host programming for comic book readers. One of the most popular comic book events is Free Comic Book Day, “an annual give-away of multiple titles, designed to draw readers—and potential readers—into the comic book store.”15 Titles range from being geared toward children up through mature audiences and often include some hardcover issues. Free Comic Book Day is organized by retailers, publishers, suppliers, and Diamond Comic Distributors. “Each year, publishers apply to provide comic books at cost to retailers, who in turn give them away for free.”16 Readers get the chance to test out brand new titles or sample books with existing characters that they have not read before.

Larger stores may limit the number of single books a customer can have for free while some stores will offer every book (close to fifty in 2012) for free. This generates foot traffic into the store for the free comic books but sales on the shop’s stock generate additional buzz. Steve Coffman recommends that libraries be run like bookstores with coffee and chairs.17 However, the comic section needs to be run like a comic shop, keeping the interest of the users in mind as a way to maintain patronage. Another recommended promotion includes weekend events and displays to tie in with the release of comic-inspired movies. Make the materials visible and easy to find and they will circulate.

Once circulated, it is important to stay informed on which books are circulating and which are collecting dust. Some libraries, like the Cleveland Public Library main branch, keep up on new comic and graphic novel titles and add titles to the library collection as they come out.18 This method is important for libraries that are looking to grow their graphic novel collection. It is imperative that libraries see what is circulating. Are certain characters popular? Specific authors? Artists? This data needs to be collected to facilitate the automatic ordering process for materials that will undoubtedly circulate without promotion. While it is great to take a risk on an indie title, knowing what the reader wants and providing it is key. In 2009, Todd Allen took a look at a small sampling of popular books such as Maus, Civil War, and Blue Beetle: Shellshocked via WorldCat. Maus had holdings in 2,032 library systems worldwide and there were 7,497 copies averaging to 3.69 copies per library. Civil War and Blue Beetle: Shellshocked returned ratios of 3.27 and 3.12 copies respectively. Allen’s conclusion was that a popular graphic novel should have at least three copies in every library system.19 While it can be risky to make an assumption about the success of a given title in a library, there are some “safe bet” titles and authors whose work should be added to the collection without hesitation.

While uniform cataloging standards, programming for adult graphic novel readers, and close monitoring of circulation can go a long way, it is important––especially in big cities or large library systems––that there be a library staff member (preferably a librarian) who is genuinely passionate about comics and graphic novels. Comic book fans are dedicated to their hobby. Their foot traffic in the library will circulate materials of all types––not just comics––and it is imperative that these users be able to locate materials that they are interested in. Graphic novels and comic books are the lifeline of libraries in the twenty-first century. If readers can’t find comics that interest them, they won’t even bother looking at other materials.

REFERENCES

- Francisca Goldsmith, Graphic Novels Now: Building, Managing, and Marketing a Dynamic Collection (Chicago: ALA, 2005), 1.

- Amanda Stegall-Armour, “The Only Thing Graphic Is Your Mind: Reconstructing the Reference Librarian’s View of the Genre,” in Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives, ed. Robert G. Weiner (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2010), 181.

- Ibid.

- David S. Serchay, The Librarian’s Guide to Graphic Novels for Adults (New York: Neal-Schuman, 2010), 1.

- Ryan Searles, interview with the author, conducted on July 7, 2012.

- Brett Schenker, ”Who Are the Comic Book Fans on Facebook?” April 27, 2011, http://graphicpolicy.com/2011/04/27/who-are-the-comic-fans-on-facebook.

- Matt Richtel and Miguel Helft, “Facebook Users Who Are under Age Raise Concerns,” New York Times (online ed.), Mar. 11, 2011, accessed Nov, 8, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2011/03/12/technology/internet/12underage.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all.

- Sarah Ziolkowska and Vivian Howard, “Forty-One-Year-Old Female Academics Aren’t Supposed to Like Comics!: The Value of Comic Books to Adult Readers,” in Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives, ed. Robert G. Weiner (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2010).

- John Jackson Miller, “The Comic Chronicles: A Resource for Comics Research,” www.comichron.com.

- Searles, interview with author.

- Jeremiah Cochran, interview with the author, conducted on July 17, 2012.

- Todd Allen, “Funnies Business: Quantifying Library Penetration for Graphic Novels,” Publishers Weekly, July 14, 2009, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/book-news/comics/article/17561-funnies-business-quantifying-library-penetration-for-graphic-novels.html.

- Serchay, The Librarian’s Guide to Graphic Novels for Adults, 4.

- Searles, interview with author.

- Carol Pinchefsky, “Free comic book day: When free comic books mean big business,” Geek Cultured Blog, May 3, 2012, www.forbes.com/sites/carolpinchefsky/2012/05/03/p1563.

- Diamond Distributors, “Free Comic Book Day FAQs,” www.freecomicbookday.com/Home/1/1/27/984.

- Steven Coffman, “What if You Ran Your Library like a Bookstore?,” American Libraries 29, no. 3 (March 1998): 40–46.

- Searles, interview with author.

- Allen, “Funnies Business: Quantifying Library Penetration for Graphic Novels.”