It Takes a Community to Build a Library

The four-year, four-city Working Together Project sent community development librarians into diverse neighborhoods across the country. Supported through funding agreements with Human Resources and Social Development Canada, the Vancouver, Regina, Toronto, and Halifax Public Libraries (HPL), worked in diverse urban neighborhoods and with diverse communities — communities we traditionally consider socially excluded. Such communities included people who are new to Canada, such as immigrants and refugees; people of aboriginal descent; people living in poverty; people recovering from or living with mental illness; people recently released from federal institutions; young people at risk; and many more.

Over this period, the project’s community-based librarians talked and engaged with literally thousands of socially excluded community members from diverse communities in the four large urban centers across Canada. The librarians took a community practitioner–based approach. This approach moved community-based librarians’ work beyond discussions among library staff on how best to meet community needs to discussions based upon the lived experiences of socially excluded community members and the librarians who engage with them as equal members of the community. Some libraries have previously worked with targeted socially excluded groups. However, the purpose of this project was not to review other works—rather, it was crucial to have community members’ library experiences drive the project, not library-based beliefs held by librarians nor internally generated professional literature. It became clear that librarians’ traditional approach to library services did not adequately address the needs of socially excluded community members. It also became clear that it is essential to begin a discussion around the use of traditional library service planning versus a community-led service planning model as the most effective way to make library services relevant to socially excluded community members.

Social Inclusion or Exclusion?

Public library staff members across Canada believe public libraries are inclusive institutions created equally for everyone in the community. Why would librarians believe otherwise? From day one, librarians frequently hear about the inclusive nature of public libraries from coworkers, traditional library users, and teachers. When community development librarians with the Working Together Project started talking with other librarians about social inclusion and exclusion, they heard many examples of library inclusiveness. For instance, they heard about free library collections which allow people to readily access and borrow materials and how libraries are already providing library services to socially excluded community members. We heard that people tend not to use library services because they are unaware of what libraries have to offer. Librarians usually draw two conclusions from these examples: (1) It is a personal choice when people do not use library services; and (2) libraries just need to do a better job marketing what they have to offer to the community. The belief that the public library is an inclusive institution is so ardently incorporated into the identity of public librarianship that questioning the social inclusiveness of

libraries rarely occurs. So is it just that simple? Are libraries the inclusive institutions they claim to be, or is something else going on?

To answer this question, community development librarians started to engage in conversations with socially excluded community members who use libraries and those who are non-library users.1 It was quickly discovered that they did not affirm the same messages of inclusiveness heard from library staff. Instead, they began to identify issues related to how they were excluded and the impact this had on their ability to utilize library services.2 Community members identified barriers in their personal lives and barriers generated by libraries, which made the library an intimidating place to enter and use.

Clearly defining and identifying social exclusion in communities can be a difficult task due to the wide range of social factors that cause people to be excluded from active social life in their community. Some of these factors include a person’s race, gender, sexual orientation, or social class. The multidimensional causes of exclusion can be compounded by individual life circumstances such as low paying jobs, health issues, low levels of education, poor housing conditions, poverty, language difficulties, and cultural barriers. Since socially excluded people continually face these issues, many struggle on a daily basis to meet their immediate needs, making it difficult for them to participate in the social, political, economic, and cultural life of their community. In conversations with individuals, community development librarians immediately began to hear about obstacles individuals experienced when they tried to access library services. The most immediate barrier to library use was the impact of library fines. The impact of fines should not be underestimated. As one community member stated during a focus group, “[I] didn’t use the library for five years, because I thought I had fines. I finally got up the courage to go back to the library and found out that I didn’t have any fines during the whole time.”

The perception of having a fine was enough to keep her away from the library. We also began to hear about barriers that traditional library users or librarians may not have been aware of, because they have never experienced them. This includes a number of issues, such as the use of library jargon (including circulation or YA), confusion regarding the arrangement of collections, a feeling of being judged and evaluated by the staff, and viewing library staff as trying to educate them. The people we talked with revealed they do not feel comfortable in public libraries, and they do not feel that libraries play an important role in meeting their daily needs. Therefore, they stay away. Yet, the function of public libraries is to play a significant role in meeting the information needs of all community members.

The Traditional Service Planning Model and Social Exclusion

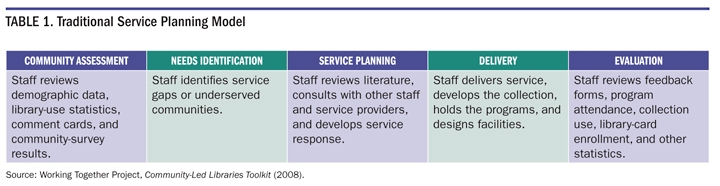

Libraries and library staff are typically representative of middle class values and worldviews,3 which unintentionally or purposely become integrated into library service planning and delivery. On the other hand, librarians are rarely, if ever, asked to theorize or conceptualize the traditional service planning model: How libraries assess and identify community needs, then plan, deliver, and evaluate the generated services. Instead, librarians are traditionally taught how to plan and create individualized services.4

The implementation of the traditional library service planning model has become second nature to the way public library staff develop services for its community. This internally generated, linear process provides library staff with an efficient and comfortable method for generating library services for communities.5

For traditional library users, the traditional service planning model generally meets their needs (see table 1). Traditional users, typically middle class individuals raised with many of the same values and other social experiences as librarians,6 are aware of and familiar with library services or feel comfortable asking for assistance. As well, librarians know the needs of traditional library users who regularly enter into their workplace and engage in conversations with staff. At times, they consult traditional users during the service-planning process. Based on these shared experiences, librarians respond in-house (through their direct engagement with members of this traditional community) to meet all library users’ needs. But does a service model which works fairly well with traditional users also address the needs of socially excluded library users and nonusers? If not, how can libraries respond?

Internally created approaches to library service planning, targeting traditional library users, currently exist in Canadian public libraries; however, these approaches do not work well when developing services for socially excluded community members. Why? Because assessing, identifying, planning, delivering, and evaluating services within the confines of the library, without directly involving socially excluded community members in every step of the process, fails to include the distinct and diverse voices of people outside the library’s mainstream customer base. Only by stepping outside of the traditional service-planning model, and engaging socially excluded community members, can librarians know if they are meeting their needs. In order to begin this conversation, librarians need to understand that they are not experts on the needs of all community members. As well, librarians should not view themselves as spokespeople for community members with whom they work. Instead, librarians are primarily experts in organizing and finding information.

Traditional techniques for service development do not allow library staff to understand or gauge the service needs of socially excluded community members. Community assessments (with the use of tools such as demographic data, library use statistics, comment cards, and community surveys) do not provide library staff with reliable and valid feedback regarding the needs of socially excluded community members. Demographic statistics provide a rudimentary contextual snapshot of the social conditions in which people live, and they do not explain the intricacies and influences social conditions have on library use. Surveys, a method of assessment libraries traditionally use, consist of predetermined, closed-end questions. This method is indeterminate, since people do not offer responses other than the ones presented in front of them.7 Comment cards are only completed by library users with the literacy skills and confidence to fill them out, and library use statistics are only applicable to community members who use library services. Traditional assessment tools do not work, because they do not access the needs of those who are not using the library—socially excluded community members.

Following the traditional assessment, community needs are determined internally by library staff. For example, it may be determined that members of the public are having difficulty searching the library catalog. In response, using the traditional service model, librarians would plan a service to address the issue. This process usually includes reviewing literature and talking with other professionals—within a library system and possibly with staff at other libraries—regarding how they have addressed the issue. Staffers then develop a response to the issue, with little or no public consultation or collaboration.

When library staff members complete the traditional service development process, they engage the community, either in the branch with a program or in the community with outreach activities. During outreach, they let the community know about a particular service that has been developed, and members of the community are invited to attend library programs. This model is limited, since the entire process is based upon a perception of community need without collaboratively engaging the community.

After an internal or outreach program is delivered, it is typically evaluated using statistical measures, including attendance or written feedback. These evaluation procedures do not take into account the impact, or lack of, the program has had on the community.8 It is very easy for library staff to report that the program has been a success. For example, after holding a community-based outreach program to review the catalog, it is deemed successful because twenty-two community members attended and seven of them registered for library cards, and many others commented that they knew how to place an item on hold. On the surface, this sounds pretty impressive. However, what was the actual impact on the community? Have we parachuted into the community, delivered a program, and then left feeling that we have helped people? Have we been able to work with community members to understand their needs and then deliver a program or service that meets those needs? How could this traditional process be structured differently or improved?

The Community-Led Service Planning Model

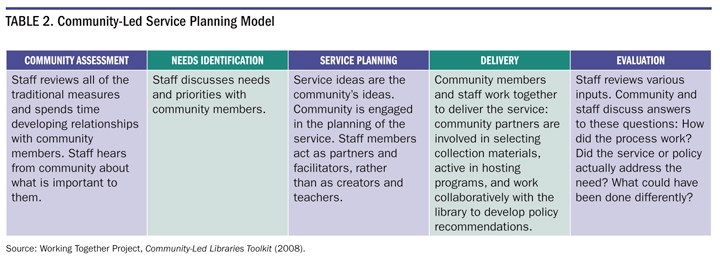

Based on the long-term work in diverse and socially excluded communities, both inside and outside the library, the Working Together Project developed a new model: the community-led service planning model (see table 2).9 Community-led service planning builds upon the traditional library service model and provides a new method, which brings library staff together with community members to identify and meet community needs. Socially excluded community members are involved in each step of the community-led service development process, from needs assessment to evaluation. This non-prescriptive model is flexible and can be applied in all library settings and to all program and service development. The community-led service planning model is effective with both socially excluded community members and traditional library users.

By entering community spaces outside the confines of the library, librarians can connect with members of the public who do not feel comfortable entering libraries. In order to make these connections, it is important to identify locations where socially excluded community members feel comfortable meeting. This includes local service organizations, shopping centers, parks, and other community identified meeting places. The locations are dependent on the specific community in which the librarian is working. An asset map is an excellent instrument for library staff to identify and conceptualize the potential connections the library could develop within a specific community, while also recognizing current community capacity and gaps.10

The development of relationships with individual socially excluded community members is the basis of the communityled service planning model. Relationship building is an essential first step, and it must continue throughout the entire service planning process, from initial community assessment through evaluation. To establish relationships, it is necessary to meet socially excluded community members who do not come to the library. This can be accomplished in various ways, such as going door-to-door, attending community events, via word of mouth, or through third-party facilitation (partnerships). It is necessary for librarians to establish relationships with individual community members, while relationships with traditional community contacts (such as local service organizations) are made to help facilitate access to community members. For example, the community development librarian working in Vancouver met with the administrators of Leave Out Violence (LOVE) several times to discuss the library’s need to talk directly with the teens coming to LOVE’s drop-in sessions. It was important for LOVE’s administrators to understand and feel comfortable with the goals of the librarian, which were to get to know the teens at LOVE and hear what they might want from the public library, before inviting her to meet with the teens.

Relationship building occurs by developing trust and mutual respect. When library staffers enter a community and engage socially excluded people, it is important to understand the historical context of the distrust some community members have with representatives of public institutions. The distrust is often due to prior negative experiences with organizations such as social services, the police, or educational institutions. Nevertheless, this distrust and power imbalance can be overcome by approaching individuals respectfully, as equal members of the community, and by actively engaging and listening to them. This approach creates a comfortable atmosphere for conversations. These conversations are the basis of relationships and the way community members can self-identify their needs. Community development librarians found that once relationships were established, they quickly heard community members identify and discuss their individual and community-based needs.

Each of the four Working Together sites used various relationship-building techniques, including facilitating group discussions and attending meetings and events in the community. For example, the community development librarian in Toronto spent regular hours at a food bank, meeting and talking with people who used that service but might not use the library. The librarian issued library cards and arranged for community professionals to come to the food bank and assist people with financial, legal, and health issues. The relationships the librarian developed linked people to the library by demonstrating the library’s commitment to meeting the needs of all community members.

Community members generate service ideas when sustained relations are in place. In order for this to occur, library staff needs to reposition its role in the community from expert to facilitator. By becoming active listeners instead of disseminators of information, librarians take information from the community and place what they are hearing within the context of library services. Each community is unique and will identify need for services based on its unique circumstances. For example, HPL’s community development librarian heard that a large proportion of food at a local food bank was spoiling because community members did not know how to prepare some of the food. Library and community members volunteering at the food bank created a service response. Food bank staff began affixing labels to the food, with the library’s phone number to call for recipes. In Regina, the community identified literacy as a major issue that they wanted to address with the library. Library staff continuously engaged the community in order to discover how the library could work with them to address their particular needs.

Once community members have identified a potential service area, they should engage and collaborate with library staff to plan a response. At one Working Together site, community members identified a need for introductory computer skills. Rather than deliver a standard prescripted library program, the community development librarian worked with members of this community to find out what their specific computer needs were. The ensuing program was a hybrid of community input and library facilitation that was adapted and changed as the program progressed, ensuring that the students’ needs were met. By creating a working relationship between library staff and individual community members, not only is the service created together, it is also collaboratively delivered. This process allows all voices to be heard and all skills utilized when developing a library-based program or service. Moreover, it provides an opportunity for community members to develop new skills, to increase community knowledge and capacity, and to enhance community-based sustainability.

The final step to community-led service planning is evaluation. It can incorporate traditional evaluation methods, while allowing the community to discuss their understanding and experience of the process. This qualitative approach lets everyone who took part in the process have a say in what worked, what did not, and whether their needs, as they defined them, were addressed in a way that was significant. As well, through dialogue with the participants, community-led evaluation provides a context for understanding how community members feel success should be measured and how feedback should be interpreted.

Evaluation is an ongoing process throughout the community-led service planning process. Targeted communities continuously evaluated service development during each stage of the planning process, truly allowing for a community-driven process to work.11

Conclusion

How can we make public libraries the socially inclusive institutions we want them to be? The community-led service planning model provides libraries with a sustainable approach to working with underserved communities. This approach, working with individuals who tend to be nonusers and socially excluded community members, increases the relevance and quality of library services. The many successes generated by the Working Together Project12 demonstrates that libraries can successfully implement this model to increase and enhance inclusiveness, and to guide librarians toward achieving our institutions’ social goals, ideals, and potential.

Editor’s note: This article is based on “Community-Led Libraries: Working Together With Your Community,” preconference session, Canadian Library Association (CLA) National Conference and Tradeshow, Vancouver, British Columbia, May 21, 2008. A previous version of this article was originally published in Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research.

References and Notes

- Darla Muzzerall et al., “Community Development Librarians: Starting Out,” Feliciter 51, no. 6 (2005): 265–67.

- Brian Campbell, “’In’ vs. ‘With’ the Community: Using a Community Approach to Public Library Services,” Feliciter 51, no. 6 (2005): 271–73.

- John Pateman, “Public Libraries and Social Class” (Public Library Policy and Social Exclusion Working Paper No. 3, Department of Information

Management, Leeds Metropolitan University, Leeds, U.K., 1999); David Muddiman et al., “Open to All? The Public Library and Social Exclusion—Volume 1: Overview and Conclusions” (Resource Library and Information Commission Research Report 86, The Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries, West Yorkshire, U.K., 2000); John Pateman, “Developing a Needs Based Library Service,” Information for Social Change 26 (2007–08): 8–28; Kerri Wilson and Briony Birdi, “The Right ‘Man’ for the Job? The Role of Empathy in Community Librarianship” (project report, Arts and Humanities Research Council, University of Sheffield, U.K., 2008), accessed Feb. 24, 2011. - This information can be found in MLIS program syllabuses found on most library school websites. Course content primarily focuses on specialized library service planning, such as collection development, services to older adults, and so forth.

- The traditional library service planning model was described by senior-level project managers, in consultation with public librarians from coast to coast, based upon shared experiential knowledge in its application in library systems across Canada. Additionally, the application of traditional service planning methods was verified by librarians across Canada at numerous national and regional conferences, who presented projects that used internal, library-based approaches for identifying, generating, delivering, and evaluating library based programs and services.

- Pateman, “Public Libraries and Social Class.”

- Jon Krosnick, “Survey Research,” Annual Review of Psychology 50, no 1. (2009): 537–67.

- Caroline Wavell et al., “Impact Evaluation of Museums, Archives and Libraries: Available Evaluation Project” (Resource: The Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland, 2002), accessed Feb. 24, 2011.

- Working Together Project, Community-Led Libraries Toolkit (Vancouver: 2008), accessed Feb. 24, 2011, .

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.