Low-Hanging Fruit: Learning How to Improve Customer Service, Staff Communication, and Job Satisfaction with Process Improvement

Process improvement has become an axiom in the business world recently. Discussions of process improvement methodologies such as Six Sigma and Lean have become commonplace in both business and public service board rooms. In 2014, the Pierce County (WA) Library System (PCLS) began conducting something of an experiment, working to discover if it is possible for a midsize public library without the resources of General Electric or Toyota to implement process improvement techniques in a real-world environment. We are, at present, about halfway through the work of our first process improvement team, but we’ve already begun to see exciting results.

The PCLS process improvement process (yes, it’s an awkward mouthful) grew out of methods of evaluating services that PCLS began using during the economic downturn. “With the recession,” said PCLS Executive Director Georgia Lomax,1 “we became very focused on evaluating how we do things. We started tracking how we were making improvements, particularly to save money to save staff so we could get through the recession.” Even as the economy improved, Lomax felt it was important that the library not lose this momentum. “We’re never going have all the money or all the staff that we want to do the things that our communities need,” she said. “Taxpayers appreciate us not wasting money, not wasting time, all of those things about being good stewards!”

Due to the recession, revenues for PCLS had dropped five years in a row. The system reduced operating expenses by $6.4 million between 2009 and 2013. Reductions had been taken from every area. In considering how to improve things, PCLS was wrestling, as almost all public service organizations are, with the Triple Constraint (also called the Iron Triangle). All projects, including the daily undertakings of work, hinge upon time, quality, and money.2 If you want things faster and cheaper, quality will go down. If you want things faster and better quality, the cost will go up.

The more Lomax learned about various process improvement models and their impact on the business world, she realized “that’s what we’ve been doing, without in effect calling it that.” Lean is the umbrella term for a practice of eliminating waste in manufacturing processes that was pioneered by Toyota and other Japanese car manufacturers in the 1970s and ’80s.3 Lean aims to provide the best service to customers while reducing or eliminating waste. The “waste” it wants to eliminate is not people, skill, or quality. The waste is that seemingly immovable side of the Iron Triangle: time.4

Lomax wanted to take PCLS’s work with process improvement further, and an opportunity presented itself. PCLS’s Reading & Materials (R&M) Department is a large department with many moving parts. The department has thirty-two staff members, eighteen full-time and fourteen part-time. Under the umbrella of R&M are Acquisitions, Processing, Cataloging, Collection Development, Interlibrary Loan, Delivery, Circulation for the Processing & Administration Center, and Audio-Visual Mends. In 2013 the R&M Department added 195,000 new items to the collection and, as of November 2014, the department had added 185,000.

“Our Reading & Materials staff works very hard, but they were struggling with increasingly complex processes and managing workloads,” Lomax said. Staff was asking both management and each other if there were ways they could do things better. “They were saying ‘We can do things better.’ and they were saying ‘We want to be a part of doing things better. We have ideas.’”

Lomax worked with consultant Catherine McHugh, PhD, to create a tutorial on process improvement for staff. “Catherine comes from an industrial background and a production line environment,” Lomax said, “and this is an area she has expertise in. So she was able to support us, and helped us develop this tutorial that taught us all the key principals about customer supplier partnerships.” Lomax was concerned that the process improvement methodology used by the library not be overwhelming. “We didn’t want to be bureaucratic. We didn’t want to create a new process that overwhelmed us. We just wanted a really grassroots, effective, day-to-day thing that we could do. . . . [W]hat we ended up with is what our staff found worked for them.”

Beyond the tutorial, the library’s next step was to form a steering team responsible for applying process improvement to the R&M Department. Team members included R&M Department staff members, the Library Materials Supervisor, the R&M Department Director, the PCLS Deputy Director, and McHugh. Department members included staff from various sections and levels, including a cataloging librarian, cataloging specialist, collection development librarian, library assistant, and virtual experience librarian.

Before the R&M Process Improvement Steering Team got started with the task of process improvement, they spent the first several meetings receiving training, both about process improvement and about participating in successful meetings. The training was fundamental to their success.

The group was given a charter outlining the specific task they were to accomplish and the parameters of the project. The task before them was to evaluate the whole department and identify the section to begin implementing process improvement. Of the charter, Steering Team member Clare Murphy, virtual experience librarian, said, “[Process improvements] had to be staffing neutral and had to be within the budget. It had to be within the computer system that we have available to us. We had to look at every area within our department and figure out which areas could actually accomplish something of value [with process improvement] given those parameters.”

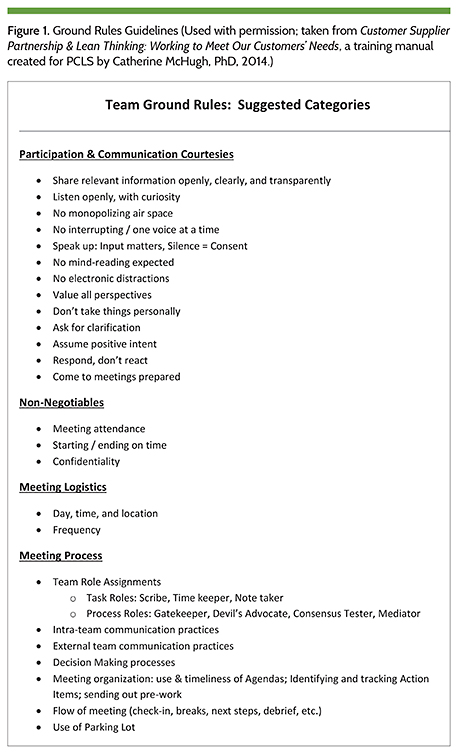

They also established ground rules (see figure 1 on previous page) for the meetings, which helped create a safe space. One of the challenging aspects of the team was that it was made up of staff from very different levels. Cataloging specialist Cathy O’Donnell said, “The rules and the charter emphasized that everyone was on a level playing field. There was not a boss, not a deputy director. We were told that in that room, in that meeting, everyone’s words had the exact same value.” Library assistant Sheri Kurfurst said, “The work we did could never have been done without the pre-work, without the charter, the ground rules. It took all the personality out of it [and] it allowed us to move forward and start being able to communicate and talk because we knew what the rules were.”

The training on process improvement methods cleared the way for success. O’Donnell said, “Catherine first taught us how to look at process improvement. She gave us the tools we would need, and the most important thing she taught us is that we are looking at the process. We are not looking at the person in the job. To remove ourselves and just look at the process and ask if anything can be tweaked. It’s not about how somebody does their job. This is how we do it now. Maybe if we try this, it will work out a little better, it will be easier to do it.”

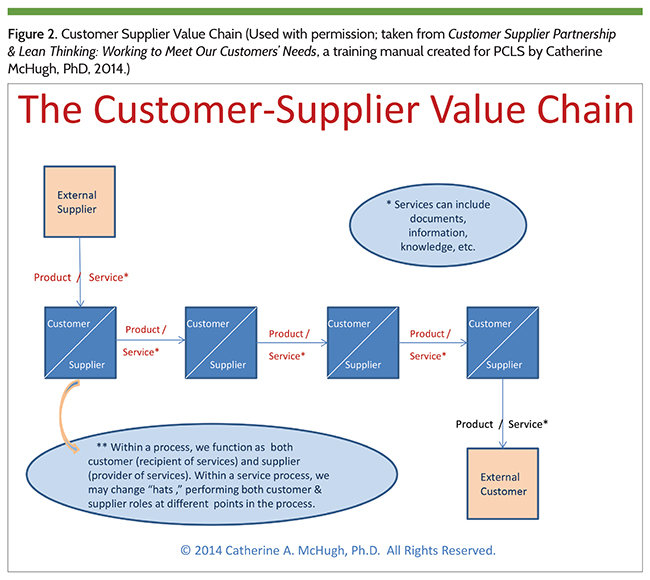

Process improvement training included learning about customer-supplier partnerships, a key component of process improvement. Customer-supplier partnerships (see figure 2) are the link each department has with another. At any point in time, a department may be a customer, or they may be a supplier, depending on which hat they’re wearing.

Library assistant Sheri Kurfust said, “My biggest thing was learning about the customer-supplier roles. [We learned] that we wear these different hats all the time. It’s really important for us to communicate to the branches, and for them to communicate to us. So they can be aware that sometimes I am acting as their customer and sometimes their supplier.” Learning about the “changing hats” of customer service was vital to the success of the project.

Public service employees are always aware of the importance of customer service. We focus on providing the best service we can. Challenges arise when we forget that the people we serve also serve us. In the case of an administrative center serving many branches, the service they provide to us is almost invariably information—information that we need to serve them the best we can. Service can break down when it appears we’ve received a request to do something we can’t do. In a “customer is always right” environment, do we move heaven and earth to do it anyway, despite the problems it will cause? Do we toss it to a “problem pile” and hope they forget they asked? Or, as suggested by the customer-supplier roles, do we put on our own customer hat and ask them for more information? Do we discuss limitations and discover an alternative solution? Do we work in an environment that encourages this kind of communication?

Another key concept that was vital to the Steering Team in choosing which section to begin process improvement was the concept of low-hanging fruit, “which are the things that would be very easy to take care of but would have a major impact on what we were doing,” said O’Donnell. Identifying sections that had a bounty of low-hanging fruit helped the team ultimately decide which section would be the first to experience process improvement.

The Process Improvement Team

The Steering Team chose the Audio-Visual (AV) Mends section of the R&M Department. The AV Mends section deals with a variety of issues relating to the care of AV. They clean discs and mend or replace damaged cases and artwork. They match up cases and sets with lost and misplaced discs. They order replacement discs to complete sets with missing discs, and they manage a “boneyard” of discs from incomplete sets to complete sets when possible. The work in AV Mends also feeds into the weeding process. O’Donnell said, “We chose them first, and part of that was we saw that there was a lot of low-hanging fruit that would be easy for us to change, it was totally within our control, we didn’t have to rely on any outsider vendors.” Within the self-contained section, it would also be easy to see and measure the impact of process improvement.

Another part of the Steering Team’s role was acting as ambassadors of the process to the rest of the department. “Coming in, there was a lot of paranoia,” said team member Matt Lemanski, collection services librarian. “Morale was low.” After multiple years of budget cuts, staff was very concerned about job security. Doing more with less at top speed, while continually feeling behind, left staff exhausted and disheartened. Sally Sheldon, library assistant in the AV Mends section said, “I had reservations. I was thinking it was a point of cost cutting. I was thinking as they make things ‘leaner’ they’re going to eliminate different things that people are doing, and that will help with the elimination of positions.”

Sheldon’s feelings are not at all uncommon when staff starts hearing terms like lean and efficiencies. Terms like these and others, like trimming the fat or being nimble, have been used for years as polite euphemisms for eliminating staff and positions. The implication of using terms in this way is that staff is made to feel like they’re the problem, not the solution. An organization that wants to take on process improvement needs to open their minds to thinking about these concepts in a new way. It is not staff that needs to learn how to do the old way more efficiently with less people. Organizations must embrace the idea that it’s the process that needs to become lean so that staff can do it well, quickly, and with high quality. “Ultimately what you want is people working at the highest level of their jobs,” said Lomax. “Doing what is the most interesting to them. So the more you can process engineer the tedious stuff the more you can have fun at your job.”

“We worked really hard to be as transparent as possible,” said Lemanski. “Because we realized very quickly that the goal of this team was not to fire people.” The Steering Team sent out communications to the department after every meeting, providing a digest of the proceedings and their action steps for the next one. Full notes of each meeting were also posted on the library’s staff website. “Our end goal was to establish a safe environment within our team to [learn about] process improvement and then extend that safe environment outward,” said

Agnes Wiacek, cataloging librarian.

Team members reached out to department members about their fears. Tris Bazzar, supervisor of the AV Mends section, said, “One of the real turning points for my people was when Cathy O’Donnell came over and said ‘This is not to have the higher ups come in and tell you how to do your job. This is to empower you to do your jobs the best you can.’”

Once the AV Mends section had been chosen, The AV Mends Process Improvement (PI) Team was formed. In addition to some of the members of the original Steering Team, the new team included Bazzar, Sheldon, and Julie McKay, library assistants in the AV Mends department; Kati Irons (that’s me!), AV collection development librarian; and Kathy Norbeck, supervisor of the Buckley-PCLS branch. Original Steering Team members included Lomax, McHugh, Lemanski, and O’Donnell.

The AV Mends PI Team began with the same training on how to participate in process improvement and how to participate in effective meetings. Despite the groundwork that Steering Team members had done ahead of time, there were some rocky moments early in the process. As the AV Selector I had worked closely with the AV Mends section for years and had been asked several times over the years to lead evaluations of the department to determine ways to streamline it, and had been stymied every time. There were simply too many moving parts. In addition, since part of my professional charge is weeding, my head is full of packed branch shelves. “One in, one out” is my clear charge from the library, but my push to weed items had sometimes seemed to the AV Mends department as disrespectful to their work.

In addition, every time conversations came up about how to “fix” things over in AV Mends, the staff who worked in the section felt defensive. They were working tirelessly every day, moving hundreds of items in and out. They were being budget conscious by attempting to fix things rather than throw them away. But here they were again, being asked to fix things instead of being acknowledged for their hard work.

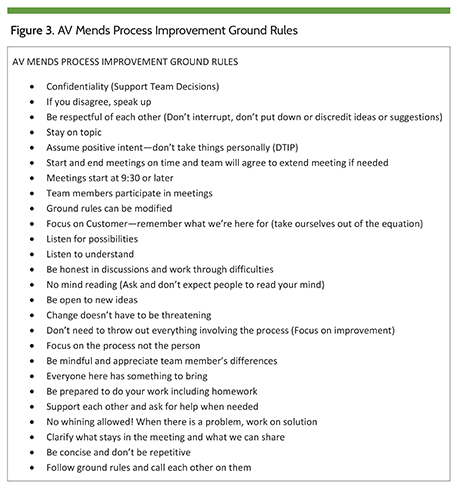

As the AV Mends team worked through the early stages of the process, including building ground rules (see figure 3) and clarifying the purpose of the team, the tension was obvious. Eventually a conversation revealed the different perspectives at play, which was an eye opener for both sides. Lemanski said, “I didn’t realize how many hurt feelings there were in that area and I didn’t realize the background around it. I think once people were able to talk about that and clear the air, it was a major road block removal.”

As hard as it is to experience, having those uncomfortable conversations is an important part of the process. One of the key components of looking at workflow through process improvement is “It’s the process, not the person.” When emotions are running high, that has to be acknowledged before team members can set the personal aside and start looking at the whole dispassionately.

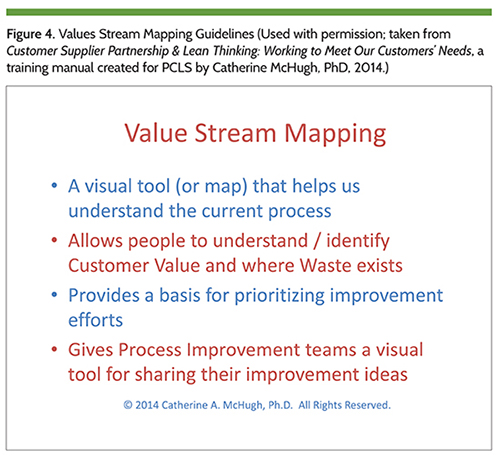

After the AV Mends team worked through the training, it was time for the group to move on to the nuts and bolts of process improvement, the Value Stream Map (see figures 4 and 5). Value stream mapping, which could also be called a workflow map, is the actual mapping of every step in a process. It’s easy to explain, but it’s very hard to do. “It’s hard for people who do a job to recognize their own steps,” said Murphy. But the breaking down of a task into the component parts is essential to process improvement, and essential in coming to understand that it’s not the person, it’s the process.

As the process owners (those who actually do the work being mapped) worked on the map, other members of the team who were not familiar with the process pushed them to be more specific. O’Donnell said “Julie [McKay] and Sally [Sheldon] were saying ‘Okay, we have the different categories of things [cleaning, mending, etc.] and they get set here.’ Well, how do they get set there? ‘Well, Wayne [Taylor, a library assistant] goes and gets it.’ Well does he get it all at one time? ‘Well, no, some come in envelopes and some come in crates.’ Well, does he get it all at the same time, or throughout the day? And they were realizing they didn’t know that Wayne was doing all this stuff.”

As finicky as that seems (discussing who goes to get envelopes and when) it was while working through that very part of the map that led to the first process improvement breakthrough for the AV Mends section. During the discussion, I mentioned that, in my role as the AV collection development librarian, I often get CDs and DVDs sent to me from the branches that really should go to AV Mends, but I just walk them over. It’s not a big deal. O’Donnell, in her role as a cataloging specialist, then said that she gets things that should go to AV Mends too, as does her supervisor. Murphy, the virtual experiences librarian who also works with our DVD vending machines, then said that, actually, she gets them too.

Initially, I had considered not saying anything. I didn’t want to complicate things, and, really, so I have to walk envelopes over to the AV Mends section several times a week. What’s the big deal? But by bringing it up, in an attempt to make the Value Stream Map as accurate as possible, we uncovered that at least five different people were receiving materials from branches that should be sent directly to AV Mends. Five different people were walking dozens of envelopes across the building every week thinking to themselves, this is a pain, but it’s no big deal. I don’t want to make a fuss.

The Results, So Far

The Value Stream Map quickly reveals the complexity of a process, and reveals the low-hanging fruit. The AV Mends PI Team ended up mapping four different processes for which the AV Mends section is responsible, and there are still more to map. In reviewing the maps created so far, several changes have already been implemented or are in the process of being implemented.

The team created a new AV Mends slip for branches to use when sending in AV problems. The old one, which hadn’t been updated for years, was a two-sided slip that included questions the section no longer needed answered and didn’t include information AV Mends could really use. The slip has been edited to be one-sided, instead of two, and the space to indicate what’s wrong with the item has been moved to the top. This removes the need to pull out the slips and search for information. The new slip has a place for branches to indicate if the item has holds, so now mends with holds can easily be identified and pushed to the front of the line.

The team also began to set criteria for when items go to AV Mends for cleaning or repair, and when they should be weeded instead. Circulation thresholds have been set for DVDs, CDs, and Talking Books, and the branches have been informed that items that have circulated beyond these thresholds should be weeded, not sent in for cleaning.

The next process improvement came from the envelope discussion. Previously, when branches needed to send items in to AV Mends, they used a crate or an interoffice envelope. Too often the crates arrived with little to no information about where it was directed and envelopes were addressed to the wrong people. Although it would have been easy to say the solution would be to train branch staff better, the team recognized that we’re a large system and the easier we make this process for the branches, the better it’s going to be. We are now in the process of implementing an AV Mends bag, created from repurposed fabric bags formerly used by our Youth Services department. Branches can stick any and all AV problems into the bag and it will go directly to AV Mends. If they are sending in a crate, they can lay the mends bag on top of the crate, and it will be delivered to AV Mends.

Sheldon and McKay both have identified areas of day-to-day work in the department that they are working to streamline. McKay said, “Walking through the mapping makes you look at all the steps you do in your job, and it makes you want to find ways to get rid of some of those steps.” After going through the process improvement training, Sheldon immediately saw a good place for change in the disc cleaning process. “Wayne would put the discs on the top shelf, and I would move them down lower, so he would have room to put more discs, instead of just moving them over by the machine to be leaned. I was moving them to the top to the bottom to the left to the right,” she said. The work of the team made Sheldon realize she wasn’t sure why they did it that way. “I was thinking what a waste of time. Why am I doing this? Just because that’s the way I’d always done it,” she said.

Branches have been excited to participate in the changes from the AV Mends PI Team. The new AV Mends slip was launched as a trial for one month, after which we asked for feedback from the branches. They asked for a few tweaks, but expressed satisfaction with the changes as a whole. When the team asked if any branches wanted to volunteer to be “guinea pigs” for the trial run of the AV Mends bags, half of them immediately volunteered. The really exciting thing about process improvement is how much people want to be a part of it when they see the results.

The work in the AV Mends section is still in process. More analysis of the items that move in and out of the department needs to be done. Training for the branches in how best to handle AV Mends requests and weeding is being created.

As the AV Mends PI Team continues its work, Lomax has plans to continue the spread of process improvement through the system. Based on the experience of the AV Mends PI Team, the Steering Team will decide which section will make up the next process improvement team within the R&M department. “As things continue in Reading & Materials, we need to start finding other areas that want to take on the process,” Lomax said. Norbeck, who served on the AV Mends team, would like to be the first volunteer: “I think one of the biggest things I took away was looking at how to streamline everything you do.”

Starting your own process improvement process may seem daunting. It’s not a fast process, and it’s not an easy fix. It requires a mental shift, a realization that this isn’t a project with a beginning and end date. It’s a new way of operating. “Make sure you’re willing to commit what it takes to get it started, and that you’re going to sustain it,” said Lomax. “If this is going to be a one-time thing I don’t know if it’s worth it. You need to trust your staff to participate and believe, truly, that they know what they’re doing and that they can do this. And then be flexible. Adjust as it goes. Focus on the process, not the people. People want to do a good job. You have to design a process that allows them to. That is so critical in how you approach things. Everyone wants to do a good job, but you have to design a process that allows them to. It makes you approach problems in a whole different way. Everyone is trying to the best they can. If you haven’t designed something right, how can they?”

Conclusion

At the end of February, the AV Mends Process Team will be reporting back to the Process Improvement Steering Team about its work so far. Training classes for branch staff on AV Mends will also begin in late February. In addition to the practical improvements, the AV Mends Process Improvement Process is having a positive impact on employee interactions and morale. Within the department, as areas of responsibility have been clearly defined, the relationship between AV selection librarian and the library assistants is much more cheerful and productive. Helping our customers has become much easier, too! From my personal perspective, I find that instead of worrying that branches are going to ask for something I can’t give them, I now see each customer as my partner in finding a solution that works.

References and Notes

1. Georgia Lomax served as the PCLS deputy director from 2006 to November 2014, when she was appointed PCLS executive director.

2. Project Management Knowhow, “Triple Constraint,” accessed Dec. 31, 2014.

3. Lean Enterprise Institute, “What is Lean?” accessed Dec. 31, 2014.

4. John J. Huber, “Prologue: The Power of Lean Transformation,” Lean Library Management: Eleven Strategies for Reducing Costs and Improving Customer Services (New York: Neal-Schulman, 2011): 1-3.

Tags: achieving excellent customer service, customer service, job satisfaction, staff communication, staff training