Capital Investment: San Francisco’s Branch Library Improvement Program

About the Author

BRIAN MURPHY is a Principal at BERK Consulting, based in Seattle. LUIS HERRERA is the San Francisco City Librarian.

Contact Brian at brian@berkconsulting.com. Contact Luis at citylibrarian@sfpl.org. Brian is currently reading Alif the Unseen by G. Willow Wilson. Luis is currently reading The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion.

This article first appeared in PUBLIC LIBRARIES NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015

Your library is very likely somewhere in the process of conceiving, funding, planning, constructing, or wrapping up a capital project or a large capital program. If you’re wrapping up, you’re probably also dreaming of the next round or series of improvements to at least some buildings.

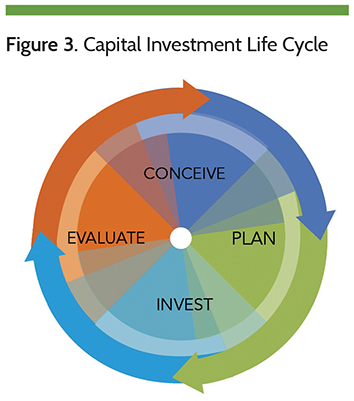

This pattern describes the capital investment life cycle for libraries. While this cycle occurs with other public facilities, including city halls and community centers, it is perhaps more pronounced with regard to libraries because of fundamental changes occurring in how people use libraries. Libraries across the country are—to use a current term—transforming. Yesterday’s library is fundamentally different from today’s twenty-first-century library.

Much of this change is fueled by rapid evolutions in technology, which influence how people access and share information. Increasing digital collections creates the opportunity to rethink spaces once devoted to periodicals and books. Libraries across the country are finding room for more community gathering spaces, study areas, and media centers. Economic and cultural changes are also contributing to the transformation of libraries.

During the Great Recession and in this time of a growing economic gap, libraries are playing important roles in skill development, job searching, career advancement, and support for small businesses.

As libraries reinvest and reinvent themselves based on what their users want inside a library (a café, makerspaces) our cities are facing an ongoing need to invest in efforts that support their communities.

San Francisco’s BLIP

San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) recently completed the largest building campaign in its history. A study by the City and County of San Francisco’s Office of the Controller evaluated the return on the public’s investment of nearly $200 million and identified recommendations for future capital programs.1 Following a brief introduction to San Francisco’s Branch Library Improvement Program, fondly known as BLIP, we will then use it as a case study to explore each phase of the capital investment life cycle.

The Need

In the late 1990s, San Francisco was facing an aging and declining neighborhood system despite a few recently updated buildings. Some branches faced potential closure due to seismic safety concerns and a lack of ADA accessibility. Moreover, San Francisco neighborhood branches were in danger of becoming outmoded and irrelevant to the demands of contemporary library users.

During this same timeframe, forward-thinking library systems across the country were embracing the emerging model of a twenty-first-century library. As described in the Aspen Institute’s 2014 report Rising to the Challenge: Re-Envisioning Public Libraries, “The physical library will become less about citizens checking out books and more about citizens engaging in the business of making their personal and civic identities.”2

The city’s jewel-box Carnegies, Work Projects Administration–era investments, and mid-century-modern branch libraries could no longer meet patron needs. They were not designed to meet contemporary demands for community and programming spaces, technological amenities, and updated resources.

The Response

In 2000, San Franciscans passed a bond measure to update and strengthen the physical structure of the city’s branch libraries, approving issuance of a $106 million bond program to build and refurbish 24 neighborhood branch libraries. This measure initiated a nearly $200 million campaign to update, revitalize, and preserve the San Francisco Branch Library system, known as the Branch Library Improvement Program. Launched in 2001, BLIP’s goals were to:

- Reduce seismic risk of the branch libraries and comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

- Replace leased facilities with City-owned buildings.

- Meet the needs of the new and evolving twenty-first-century model.

Build a system-wide support service center for library collections and branch operations.BLIP renovated or rebuilt 24 of SFPL’s 27 neighborhood libraries. Sixteen historic branches were renovated, four leased facilities were replaced by city-owned buildings, three branches were replaced with new buildings, and the system’s first new branch in 40 years was constructed.

The Impact

With completion of the program in 2015, the San Francisco Controller’s Office, working with SFPL, engaged BERK Consulting to conduct a review of the program and to report on BLIP’s contributions to the community. BERK’s report shows that:

- For every dollar invested in BLIP, San Francisco realized a return of between $5.19 and $9.11 over the twenty year life of the investments.

- The capital investments and additional operating spending associated with BLIP contributed more than $330 million in indirect and induced benefits to the San Francisco economy.

The report describes BLIP’s contributions to the community in four key areas (see figure 1).

Serving San Francisco in the Twenty-First Century

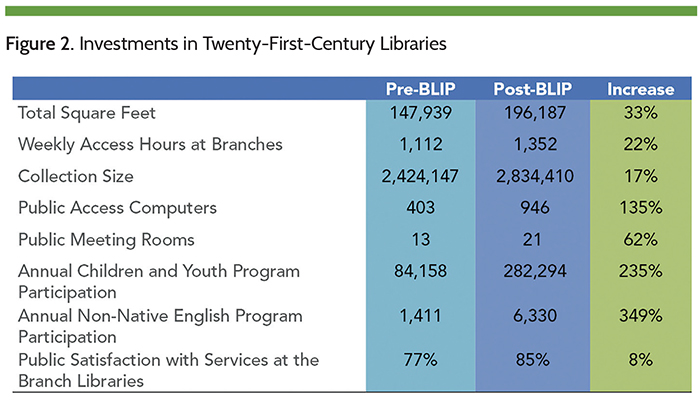

By updating safety and accessibility limitations of older buildings, BLIP preserved San Francisco’s beloved system of neighborhood-based branches. Moreover, the BLIP investment transformed aging facilities into twenty-first-century libraries, with expanded spaces for community events and library programming, dedicated places for children and teens, increasingly advanced technologies, and updated and expanded collections (see figure 2).

Catalyzing Neighborhood Vitality

SFPL amplified its investments in branch libraries to become investments in neighborhoods. Library investments were used as community development catalysts, sparking, responding to, and advancing community aspirations for not just their libraries, but also for their neighborhoods. This was not the easy path. Specific sites, creative public/private partnerships, and particular designs were needed to make it happen, both complicating the process and greatly magnifying BLIP’s contributions.

Preserving Resources and History

Through BLIP, new branches are located with easy access to residential populations and public transit, have energy efficient designs and fixtures, incorporate the use of recycled materials, and feature natural lighting, windows that open, and environmentally sound materials. BLIP also helped enhance San Francisco’s physical connection to its history by preserving the architectural integrity of historic branches.

Stimulating Economic Activity

With stratospheric real estate costs and a high cost of living, San Francisco is an extremely challenging place to live or run a business for many. The community has established policies and contracting requirements to advance shared prosperity, increase affordable housing, and increase access to living wages. BLIP met and exceeded minimum requirements for local hiring, strengthening San Francisco’s ecosystem of small businesses and providing employment opportunities to local residents.

The Capital Investment Life Cycle

Using BLIP as a case study, let’s explore the sequential and repeating steps we’ve described as the capital investment life cycle and identify recommendations for your library’s current or upcoming capital investment program (see figure 3).

Step 1: Conceive and Fund

Your first step is to sketch out your capital program in broad strokes, identifying the need, your preferred approach, and how the investment will be funded.

Engage your partners to leverage complementary skills and abilities. The success of BLIP was in large part due to its success as a partnership among SFPL, San Francisco Public Works, and the Friends of the SFPL. In managing the program, Public Works contributed expertise implementing large-scale capital investments. The Friends supplemented its public sector partners in three critical areas: (1) successfully advocating for passage of the bond measure; (2) raising private support to augment public investments; and (3) supporting neighborhood-level community engagement.

An important part of the Conceive step is identifying the expertise and activities that will be necessary for success. If your institution cannot or should not play these roles, lean on your friends and allies. Friends of the SFPL raised approximately $10 million via a grassroots, neighborhood-based community library donation campaign to cover the costs of furniture, fixtures, and equipment in all 24 branches.

Make the case and raise support. The ambitious, programmatic approach established under BLIP required its own funding stream because system-wide investments could not be supported by San Francisco’s regular capital improvement budgets alone. This funding came in the form of a voter approved bond measure, other public funding, contributions to the Friends of the SFPL, and earned income in the form of interest income and developer fees. The Friends worked hard to build the public support necessary to secure passage of the BLIP bond measure and to raise local dollars to support the effort. This community fundraising contributed needed dollars, and also generated neighborhood-level excitement and ownership of the improvement projects.

One thing San Francisco did not do is look ahead to the completion of the capital program to describe and even quantify the benefits it will generate. Projected return on investment calculations must be approached very carefully, as they will be viewed critically by some. Incorporate a wide range of defensible benefits based on experiences in other communities.

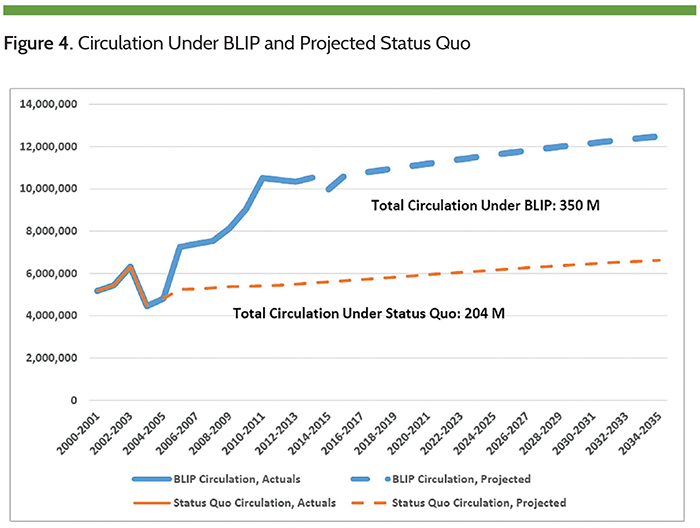

Figure 4 illustrates the increase in system circulation attributable to the BLIP investment. BLIP also involved a significant increase in annual operating expenses—SFPL assumed that the updated branch libraries would allow it to increase its level of direct service significantly. If, in making its case to the public, SFPL had assumed a 50 percent increase in usage, it would have committed to a twenty-year return of between $2.50 and $5.00 for every dollar to be invested in BLIP. This aspiration would have been proven to be well below the actual returns realized.

When possible, take a programmatic, not incremental, approach. The many community benefits generated by BLIP are largely attributable to the fact that investments in individual libraries were designed and implemented as a single, coordinated program, not as individual and incremental activities. In conceiving BLIP, SFPL and its partners established a bold, system-wide program with ambitious goals, a relatively compressed timeframe, and a systematic approach to project management and public engagement. This process led to a renaissance of San Francisco branch libraries, highlighting their role as neighborhood anchors. In addition, community standards for environmental quality and local hiring for construction were realized. It also supported learning across the system and efficiencies in project management and execution.

Approaching library improvements programmatically also allowed SFPL to invest equitably across the entire system, ensuring that branches city-wide were comparable in terms of technology, amenities, and quality. It is likely that if this investment program had been completed in a more piecemeal manner, inequities would have manifested across the system.

Review best practices and lessons learned. As projects move from conception to the more concrete planning of the next phase, take time to review national literature and any historical information you may have about lessons learned from previous projects.

Step 2: Plan

In transitioning from conception to planning, you begin a more detailed process of determining the improvements to be made in individual buildings. Reinvent when necessary and build with the future in mind. Through BLIP, SFPL created an opportunity to rethink and renew libraries before reinvesting. Parallel and complementary inputs were used to look ahead and build toward the future. Community engagement was critical, providing direct input from patrons about their desires for their library. Futurist thinking, research, and planning were also important, considering how society will continue to change, and how libraries can continue to adapt to evolving needs.

BLIP’s design guidelines ensured that architects and engineers were selected based first on quality, innovation, and the long-term durability of their projects, further contributing to the suitability and longevity of the buildings. Acknowledging limits of what can be researched, imagined, and planned for, BLIP managers deliberately incorporated flexibility into branch library reinventions. Movable and adaptable features create the ability to continue to improve and evolve as usage patterns and technologies change.

While investing in library facilities, invest in your community. Look beyond libraries to appreciate your community’s broader goals. Look to community-wide or discipline-specific needs assessments and plans or other articulations of community aspirations, including those drafted by both the public and non-profit community.

BLIP’s planners recognized that investments in public facilities often create an opportunity to advance community and economic development goals. SFPL went to great lengths to maximize the positive impact that branch improvements would have on the local community by tailoring each branch project to the specific needs of the community it serves. The Visitacion Valley Branch was intentionally sited on a property where a vacant storefront had long been a blight on the neighborhood. The Mission Bay Branch, the system’s first new branch in 40 years, was designed to meet a range of community needs and has helped shape this developing neighborhood of San Francisco. It provides the neighborhood’s first free community gathering space and is housed in a mixed-use building along with affordable senior housing, retail space, and an adult day health center.

While this approach added to the complexity of the BLIP effort, at times greatly complicating development deals and library design, SFPL’s vision of branch libraries as community development engines carried it through these challenges and resulted in branch libraries that continue to both reflect and energize individual neighborhoods. Reinvented branch libraries are contributing to the vitality of streets and local businesses, supporting local schools and community-based organizations, and serving as community focal points and meeting places.

Engage community members in planning improvements in their branches. Explore your community members’ dreams for the future of their library. Invite their ideas and cultivate their ownership, remembering it’s not your library.

The BLIP process included meetings at each branch across the city that engaged community members in imagining and prioritizing potential improvements. As with other choices made in implementing BLIP, this approach added cost and complexity, but contributed tremendously to BLIP’s success. In simple terms, by listening to and delivering on local community desires, SFPL created tailored branches that generate more use and have more community impact than more generic branches would have had. In addition to this impact on “product quality,” public engagement also produced a level of public and neighborhood ownership that will provide long-lasting returns.

Establish a baseline and processes to capture investment data. Before the first shovel of dirt is turned, take time to gather baseline data and create simple ways to collect information as the capital program progresses. How many square feet do you have in existing branches? How many public access computer terminals? How many public meeting spaces? How many titles are on hand for adults, children, and other populations? How

much energy and water do existing buildings use on a monthly or annual basis? This information will be invaluable when you evaluate your investments during the concluding phase of your capital investment program process.

Step 3: Invest

In this phase, you translate dreams and plans into on-the-ground investment by renovating existing buildings or breaking ground on new facilities.

Learn as you go and fix problems as they arise. In planning an ambitious capital program, don’t hope that planning will enable you to avoid problems. At best, a rigorous planning process and strong project management systems will allow you to respond well to challenges as they arise. BLIP’s centralized project management created an opportunity for ongoing learning and the implementation of lessons learned over the course of the fourteen-year program. Community engagement techniques that did work were replicated in neighborhoods across the city. Interior furnishings that didn’t work well in one branch weren’t used in other branches.

Continue to engage and respond to the public. The BLIP public engagement process went far beyond a token “visioning exercise” or “listening session.” In several branches across the system, public input had profound impacts. After flatly rejecting the architect’s proposal for building renovations, the Richmond Branch community was invited to a three-day, hands-on workshop during which residents helped sketch the design for their reimagined library branch. Based on input from the Bayview community, San Francisco’s contracting policies were hyper localized to ensure neighborhood residents were employed in the improvement of their own branch library.

Deliver on promises made. A capital program is a tremendous opportunity to demonstrate good management and positive results to your public. It also creates a significant opportunity to disappoint. Partners, public sector decision-makers, and the public have stepped up to fund the project. Members of the public have been engaged in dreaming about and planning for the desired future of their libraries. Promises have been made and expectations have been raised.

It’s critical that these promises are upheld and expectations met. In the case of BLIP, the buildings were an important component in this, and so too were concurrent service enhancements, including additional staff and open hours. Branches that underwent the BLIP treatment were truly better in all ways. Ultimately, the BLIP process and outcome changed the community members’ relationship with their local branch library and with SFPL overall. BLIP increased visibility of the system and activated and strengthened community support for the library as an institution.

Collect consistent and high quality data as you go. Building on the baseline you established in the previous section, continue to gather data as you make investments. How many square feet are added to community gathering spaces, meeting rooms, and other functions? How many public access computers and other amenities have you added? What green building techniques have been deployed and how do they impact your energy costs? You’ll need this data soon, in phase four.

Step 4: Evaluate

Assessing the entire project is an important element in measuring the success of the program.

Celebrate! Take time to celebrate hard work, challenges overcome, and successes achieved. Ribbon cuttings and grand (re)openings are important community events that acknowledge contributors and raise awareness about the value of public libraries and the importance of investing in their renewal. Remind your full community of their libraries, making some community members think again about how these institutions are relevant to them or others.

Gather lessons learned and measure the impact you’ve made. You’ve learned a lot over the course of your capital program: things you would do again, choices you would make differently, and mistakes you would avoid. Compile these lessons and save them for future reference while continuing to evaluate the buildings’ performance over time. There will be additional lessons learned as investments age and as usage patterns and technology change around them. By continuing to monitor the success and longevity of these investments you can continue to improve its system and establish best practices for future investment programs.

Estimate the return generated on the public’s investment by comparing pre- and post-investment usage of the system, energy cost-savings, and other

differences. Look beyond these metrics to assess the contributions made to neighborhoods, the local economy, and other factors that were intended or accidental beneficiaries of the investment.

Share lessons learned and demonstrate value of investment. Be proactive in sharing the good news. Contribute to national best practices by sharing lessons learned and insights gained with others in the library field. You’ve laid the foundation to capitalize on the capital improvement program by continuing to raise the library’s visibility and responsiveness to its community. In San Francisco, additional service hours were added to the branch libraries at the culmination of BLIP. Strengthen your relationship with the public, demonstrating that you have delivered on promises made and deserve to be trusted in future investment cycles.

When you’re done, enjoy your new libraries and think about the next cycle of adapting to unceasing evolutions in how your patrons want to use their library. Or perhaps you’ve already started.

Reference

- Aspen Institute Dialogue on Public Libraries, Rising to the Challenge: Re-Envisioning Public Libraries (Wash., D.C.: The Aspen Institute, Oct. 2014).

- Reinvesting and Renewing for the 21st Century: A Community and Economics Benefits Study of San Francisco’s Branch Library Improvement Program (Sept. 2015), accessed Dec. 16, 2015.