Re-Envisioning the MLS The Future of Librarian Education

About the Authors

JOHN BERTOT is Professor, LINDSAY SARIN is MLS Program Manager, and PAUL JAEGER is Professor, iSchool, University of Maryland College Park. Contact John at at jbertot@umd.edu. Contact Lindsay at lcsarin@umd.edu. Contact Paul at pjaeger@umd.edu.

John is currently reading What If? Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions by Randall Munroe. Lindsay is currently reading My Life on the Road by Gloria Steinem. Paul is currently reading The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey.

This article first appeared in PUBLIC LIBRARIES NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015

The last several years have been marked by a number of societal changes that include, but are not limited to, the shifting nature of our economy, the workforce skills needed to succeed in a reinvigorated job market, advances in technology, the evolving nature of information, transformations in education and learning approaches, and the rapid demographic shift occurring in our communities.1 Any one of these challenges can have a significant impact on individuals, communities, and institutions. Collectively, the shifts are seismic and impact how we learn, engage, work, and succeed moving forward (see “Re-Envisioning the MLS: Issues, Considerations, and Framing” for additional details). Public libraries in particular have been deeply affected by the changing social, economic, technological, demographic, community, and information landscapes—so much so that various initiatives are exploring the future of public libraries.2 Exploring the future of public libraries, however, also requires us to consider the future of public librarians—and how we prepare them for a dynamic and evolving service context.

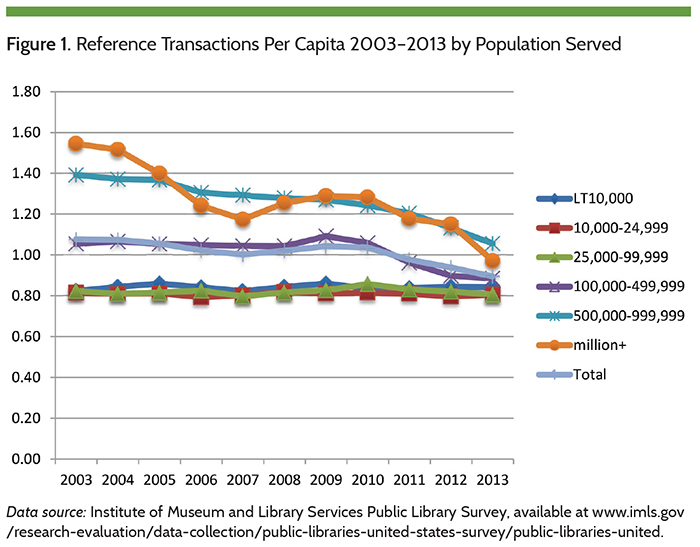

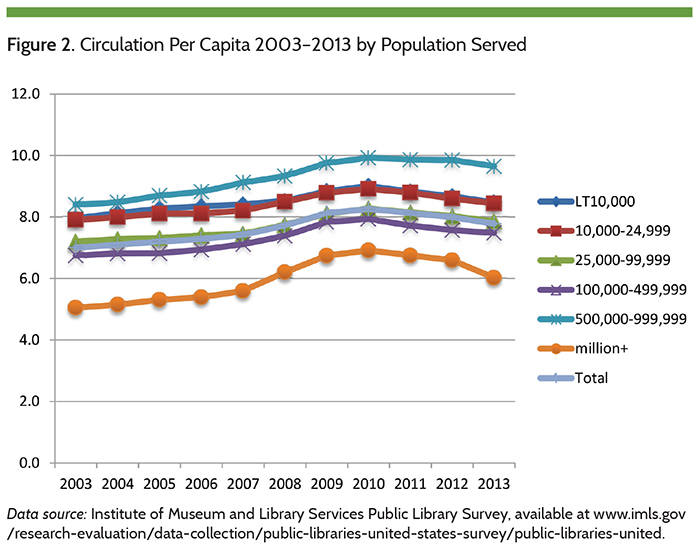

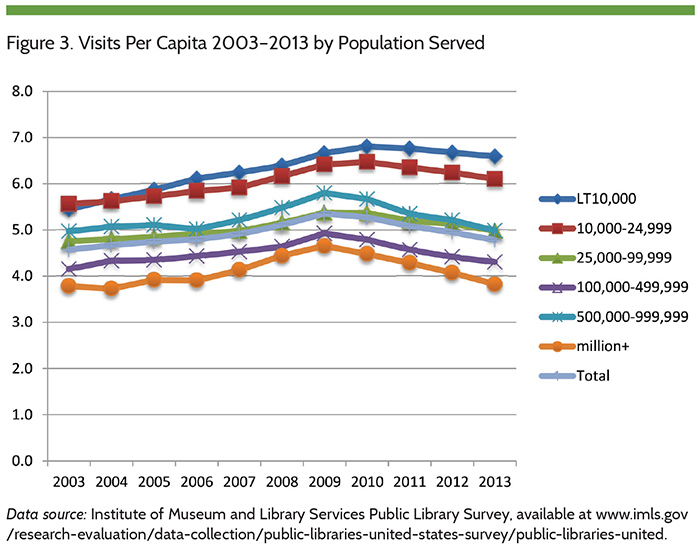

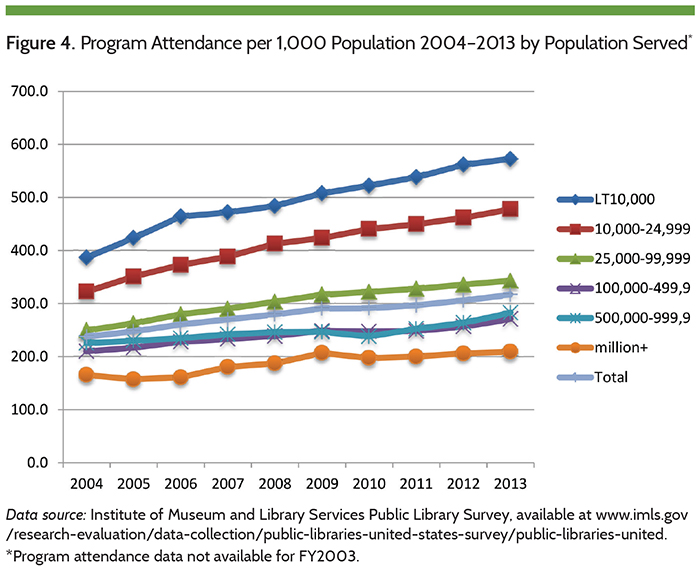

Public libraries are in transition, bridging the print, physical, digital, and virtual worlds. We have entered an “anytime, anywhere, any form” mode of meeting the information and other needs of our communities. As we go through this transition, some services are in decline, such as reference (see figure 1). Circulation and visits per capita are declining to more normal rates after a notable spike during the recessionary years (see figures 2

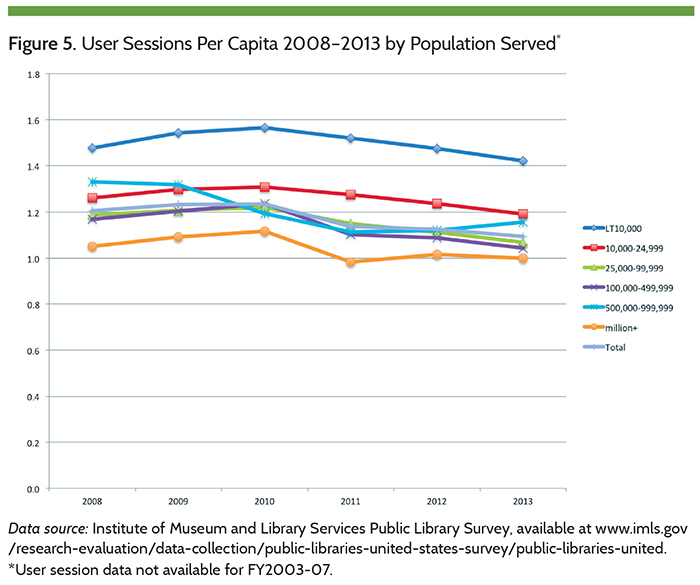

and 3). Time will tell if these will fall further. The future, however, seems more focused on community engagement (see figure 4) as programs and program attendance increase substantially. Interestingly, there is less demand for public access computers (see figure 5), but that may reflect ncreased device ownership by individuals who use a public library’s Wi-Fi connectivity. These trends reflect newly released findings from a Pew survey of library users that indicate a decline in library visits in the last year by those sixteen and older, from 52 percent in 2012 to 46 percent in 2014.3

On the one hand, public libraries are honoring their tradition of providing access to materials in various formats as they have done since the mid-1800s. On the other hand, public libraries now ensure that their communities are digitally ready and inclusive, have access to and help with a wide range of social and government services, can respond to and recover from disasters, benefit from new and innovative services through partnerships with other community institutions, and receive social justice.4 All of these currently evolving and expanding contributions of public libraries to their communities represent a critical opportunity to re-envision and recreate not only the public library, but also the master of library science (MLS) degree program to both prepare students for the shifting roles that public librarians now play and ready them to be change agents and drivers of social innovation in their communities once they are in the field.

On the one hand, public libraries are honoring their tradition of providing access to materials in various formats as they have done since the mid-1800s. On the other hand, public libraries now ensure that their communities are digitally ready and inclusive, have access to and help with a wide range of social and government services, can respond to and recover from disasters, benefit from new and innovative services through partnerships with other community institutions, and receive social justice.4 All of these currently evolving and expanding contributions of public libraries to their communities represent a critical opportunity to re-envision and recreate not only the public library, but also the master of library science (MLS) degree program to both prepare students for the shifting roles that public librarians now play and ready them to be change agents and drivers of social innovation in their communities once they are in the field.

Launching the Initiative

It is in this context that the University of Maryland iSchool’s MLS program in conjunction with the Information Policy and Access Center (iPAC) launched our three-year initiative to Re-Envisioning the MLS.5 The initiative sought to answer the following questions:

- What is the value of an MLS degree? In particular what is the value of the MLS:

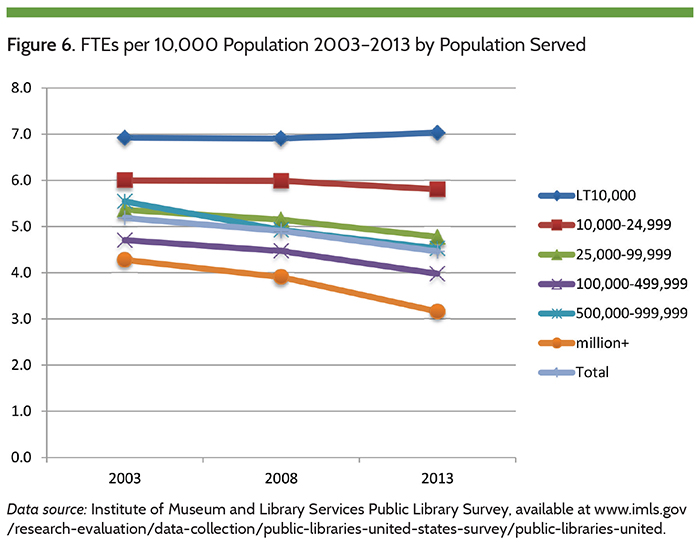

o In a climate in which public library leaders indicate that they are specifically seeking non-MLS (and its variants) librarians and there are reductions in librarian staff (see figure 6)?

o At a time when higher education is more expensive than ever?

o At a time when the value of advanced degrees writ-large are being questioned? - What does and should the future MLS degree look like? But also, asking is there a future for the MLS degree—and if so, what is that future?

- What are the competencies, attitudes, and abilities that future library and information professionals need? And, how do we incorporate these into an MLS curriculum?

We also asked more specific questions related to the University of Maryland’s MLS program.

The Re-Envisioning the MLS initiative was designed as a three-year undertaking involving:

- Year 1: community and stakeholder engagement, discussion, and thought-leader presentations to identify key issues, trends, needs, concerns, challenges, and opportunities;

- Year 2: review of findings, curriculum and program design, and community and further stakeholder engagement based on the key findings from Year 1 activities; and

- Year 3: operationalization and implementation of a re-envisioned MLS that reflects Year 1 and 2 efforts.

Although the effort focused on what graduates will need from four years out and beyond, we do not view this as a “one and done” initiative. There will be continual stakeholder and student engagement as part of an ongoing program evaluation and as part of our ALA accreditation reporting and reaccreditation processes in the years to come to ensure that our program reflects the existing and emerging needs of libraries and the communities that they serve.

The Process

The Re-Envisioning the MLS initiative involved multiple activities that included:

- The creation of and active engagement with the MLS program’s inaugural advisory board.

- A speaker’s series, which brought in influential members of the information community who provided thought-provoking views on trends, current and future issues, and challenges and opportunities in our field (see hackmls.umd.edu for archives and summaries).

- Engagement sessions, which were dialogues between students, staff, faculty, and the broader public about selected topics for consideration in relationship to MLS programs (see hackmls.umd.edu for archives and summaries).

- Stakeholder/community discussions, which included numerous regional visits throughout Maryland, discussion sessions with the Maryland Association of Public Library Administrators (MAPLA), attendees of the 2015 Maryland Library Association conference, the Division of Library Development and Services (Maryland’s state library agency), the State Library Resource Center (Maryland’s State Library), the Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (LBPH), and regional libraries throughout the state to engage information professionals from around the state in this dialogue.

- Blog entries, which documented progress, summarized presentations, and offered insights based on what we had learned along the way.

- The development of a white paper, which identified key issues, trends, and developments and their potential impact on information organizations and professionals.

- Environmental scanning and research, which included reviewing key studies, analysis, data, and reports—particularly those focused on the future of information professions and information organizations such as libraries, archives, and museums.

These efforts provided multiple perspectives and inputs that informed the findings from the initiative. We do acknowledge, however, that though our efforts were extensive, they were not exhaustive and thus there are limitations to our findings.

Not the First (or the Last) Discussion

The topic of the changing nature, or lack of changing nature, of library and information science (LIS) education is an almost constant in the library community. Our field has a long history of self-reflection and self-doubt about the education programs preparing them for the profession. This is despite the fact that formalized education programs for librarianship date back 130 years in the U.S., and that the standardized MLS, and its name variants, degree are now more than fifty years old.

In 1985, a library school professor created “An Anthology of Abuse” documenting the different criticisms of library education, ranging from the perceived limitations of the faculty to the perceived limitations of the curriculum to the perceived limitations of the students.6 The list was expanded only a few years later.7 In more recent years, books have suggested that the problems of library education are rooted in a lack of attention to theory, too much attention to theory, too much emphasis on research, and the design of the MLS degree itself.8 There has even been a book arguing that a library education should be done in an apprenticeship model outside of the university and focusing only on books.9 In recent years, blogs and social media have expanded the discussion. The library school student-created and run blog, Hack Library School was founded to create a venue in which current students could learn how to best “hack” their own education. Annoyed Librarian also critiqued the value of library school.10 Hiring Librarians, a blog created as a result of a “frustrating job hunt,” has discussed LIS education and/or library schools many times including an interview where the anonymous academic librarian interviewed specifically said, “do not go to library school.”11 The American Library Association (ALA) and Association of Library and Information Science Educators (ALISE) have also had a series of ongoing discussions regarding the future of LIS education including the Library Education Task Force Report, a publication of the ALA’s Core Competencies of Librarianship, a set of revised ALA Accreditation Standards, and an Institute of Museum and Library Services-funded project at Simmons University.12

For all of the perceived problems over time with library education—and the MLS in particular—it is hard not to look at the discourse and conclude that the library profession tends to see the “new” as a crisis. Outcry over newspapers, recorded music, films, and the Internet and their potential threat to librarianship as a profession and libraries as an institution are easy to point to as examples of threats to libraries and librarianship.13 In 2005, Andrew Dillon and April Norris applied the term “crying wolf” to describe the seeming need for librarianship to incessantly fret about education in the field and suggest that the perception of crisis is a way to avoid substantively changing.14 This avoidance of evolving was labeled the “panda syndrome” in the 1990s, reflecting an animal that has notably failed to evolve to its own detriment.15 In short, instead of perceiving changes and challenges in society and technology as opportunities to evolve and improve education and the impacts made by MLS program graduates, many in the field react to each change or challenge as “an existential crisis that threatens the nature of the field.”16

Public libraries have been especially involved in the discussion on the future (or lack of future) of LIS education. Based on our engagement sessions, regional site visits, a large group discussion with the Maryland Association of Public Library Administrators, our MLS Advisory Board meetings, and other activities, several public library systems in the Maryland, D.C., and Virginia region indicated that they are not—or will not be—seeking MLS/MLIS-degreed professionals in the same numbers because of funding concerns and/or that their current and future community needs call for more than what current MLS/MLIS programs teach their graduates. Rural libraries (and librarians) in particular noted that they typically have one MLS librarian and that fact was not likely to change. Further, in some circles, a discussion has begun as to whether an MLS degree is needed to serve as a professional librarian—with some indicating a desire to change state policy and law, if necessary, to pursue such a change.

It is within this context that the below summarizes and presents the findings from the Re-Envisioning the MLS report. The full report with its findings is available here. The article concludes with a series of recommendations for LIS educators and programs, ALA accreditation, practice, and employers.

The Shift in Focus to People and Communities

Discussions on the “big shift” in libraries have been dominated by digital technologies and content—mobile, broadband, public access technologies, digital resources such as e-books and licensed resources, building national digital platforms, streaming content, content creation, and more. Though the “digital shift” is significant, another major shift that has occurred over the past decade, perhaps influenced by the digital shift, is a change in focus for public libraries from their holdings to the individuals and communities that they serve.

Public libraries have been on the forefront of the user-centered design approach for information resource and service development as part of the curriculum for decades; however, the LIS education system has been focused primarily on library-centric user design based on a set of pre-determined standards, services, and operations. The shift articulated as part of the Re-Envisioning the MLS initiative is more fundamental, and involves actively meeting user needs at the point of need (just-in-time) to enable the meaningful transformation of the individual rather than through more passive interactions without determining if the individual can actually use the information to meet his/her needs.

Increasingly, people come into the library with life issues such as access to food, social services, and/or health insurance. The passive or transactional approach provides information and a description of resources. A proactive and individual/community-centered approach would be having on-premise social services, public health specialists, interactive STEAM-based (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) makerspaces, and other more interactive and immersive services that facilitate the transformation (learning, skills, meeting the life need) of the individual. We have seen public library systems using this approach including the hiring of social workers at various urban library systems, the Baltimarket program, summer lunch programs for children, and many others.17

Core Values Remain Essential

Participants in the Re-Envisioning process indicated that what distinguished the MLS from other professional degrees was a set of values that framed who we are as information professionals but also what we are to our communities. In short, these values determine “what it was to be a librarian,” as emphasized by library leaders in one focus group. Participants across a variety of focus groups emphasized the following core values:

- Access: ability to access information freely and in a manner suited to an individual’s needs and abilities.

- Equity: access to information and resources regardless of the information professional or user’s beliefs, race, ethnicity, gender-identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or abilities.

- Intellectual Freedom: free and open access to information without censorship or restrictions.

- Privacy: ensuring the confidentiality of user and staff personal information as well as the information and resources they seek, use, transfer, and so on.

- Learning: providing instruction and educational resources that promote education and meaningful learning in an inclusive and equitable manner.

- Community: seeking to understand and serve the needs of the specific community being served while maintaining the values of access, equity, intellectual freedom, and privacy.

- Inclusion: providing information services at all ability levels and regardless of those factors outlined in the value equity.

- Human Rights: supporting and promoting human rights directly and indirectly by equipping community members with the skills and resources necessary to pursue greater equality in various arenas.

- Social Justice: providing free equitable access to information that promotes the user’s ability to gain equal economic, political, and social rights.

- Preservation and Heritage: providing current and future access to records, both analog and digital. Embedded in this is the need to safeguard against inequitable or privileged selection or destruction of materials based on prejudiced, privilege, or inequitable biases or assumptions.

- Open Government: ensuring transparency, public access to, and participation in the creation of government information.

- Civic Engagement: providing access and meaningful learning opportunities that foster participation in issues or processes affecting the community served.

These values focus on ensuring that all individuals can seek opportunity and success through information.

Competencies for Future Information Professionals

Participants indicated that MLS programs must, at a minimum, provide their graduates with the following competencies through coursework, application, and practice. The competencies identified are highlighted by quotes from participants during the Re-Envisioning process:

- Ability to lead and manage projects and people, even if graduates do not intend to become a supervisor, director, or manager. “If I could tell someone going into librarianship one thing it would be: expect to be a manager; you’re going to end up managing whether you want to or not.”—Librarian

- Ability to facilitate learning and education either through direct instruction or other interactions.

“I want my staff to be facilitators.” —Public Library Director - Ability to work with, and train others to use, a variety of technologies. “Staff need to be both up on the latest technologies and be able to help individuals use those technologies”—Academic Library Director

- Marketing and advocacy skills. “Marketing ‘writ large’ not just to other librarians or the users we have.”—Librarian

- Strong public speaking and written communication skills. “No more people who only want to hide in the stacks.”—Public Librarian

- Strong desire to work with the public in general and a wide range of service populations in particular. “We have to be dynamic ‘people-persons’ and be comfortable with a BROAD spectrum of people.”—Library Staff

- Problem-solving and the ability to think and adapt instantaneously. “I want a risk-taker. It doesn’t have to be perfect to get started.”

—Library Manager - Knowledge of crisis management techniques and social services training. “You never know what you’re going to encounter, and you need to train your students to ‘expect the unexpected’ and be prepared for it.”—Director

- Knowledge of the principles and applications of fundraising, budgeting, and policymaking skills. “As a director I had to go back to school to learn finance, budgeting, fundraising, the policymaking process, etc.”—Director

- Relationship building among staff, patrons, community partners, and funders. “We don’t have to, nor can we, do everything. What we can do is partner with others who can help us achieve our goals and the goals of the community.” —Librarian

- Documentation and assessment of programs. “Just like schools we have to be able to show funders their return on investments.”

—Youth Librarian

These competencies emphasize three underlying aspects of MLS education: people, technology, and information—but expand to include knowledge of organizations, management, leadership, policy, collaboration, communication, communities, and data. Simply put, graduates need to understand—and be comfortable with—the broader ecosystem in which they provide information services and resources.

The Elephant in the Room: Is an MLS Still Relevant or Necessary?

With the changing nature of libraries, archives, and other information organizations—and their roles in the communities that they serve—the inevitable question of whether an MLS is still relevant or necessary arose throughout the entire Re-Envisioning process. Discussions of this topic were both passionate and conflicted. The following summary attempts to capture the various expressions on both sides of the debate:

- There was a sense that an MLS is not required—nor perhaps desirable—for all aspects of library work. For example, having human resources, business managers, communications staff, information technology staff, web designers, and other operations staffed by those with expertise and relevant degrees was preferable.

- Most participants indicated the need for MLS-holding individuals for leadership positions in libraries. An MLS imparted not just skills and an understanding of librarianship and the information professions, but also core values such as intellectual freedom, privacy, access, equity/social justice, open government/civic participation, and learning as articulated above.

- Some indicated that the field needs to look more broadly than an MLS and seek those with:

o education and/or instructional design degrees for digital readiness, literacy, and instructional activities;

o design degrees for “making” and creative activities;

o social work experience for increasingly social service-related services;

o knowledge of public health for a range of health information-related initiatives; and analytics for “smart community,” hacking, coding, and other data-related initiatives. - Some insisted that the MLS degree was essential, and not just about skills, foundations, and principles, but also signified the importance of the library and information professions and individuals with the degree as professionals.

- Others indicated that what makes successful information professionals was less about aptitude (which could be taught) and more about attitude, particularly those who wanted to engage the public, were outgoing, innovative, creative, and adaptable.

- Those in rural and small public libraries indicated that MLS-holding professional librarians, due to pay scales and other constraints, would never be a majority of their workforce and thus they actively engage in a range of paraprofessional recruitment and training.

The varied views were not a surprise. What was a surprise, however, was the open and candid debate around the need for an MLS “no matter what.” There is an increasing acknowledgment that those with other degrees and skills might meet various needs better and that our libraries should be open to those with a range of degrees other than the MLS. Thus the key question that emerged was: What makes the future MLS valuable and valued?

Opportunity for All, Access for All, or Something Else?

Though our libraries have long stood for, and information professionals value, social justice and equity of access, the growing “gaps” (income, education, literacy, employment/employability), combined with the erosion of a public sphere that provides robust social and other services to assist those in need, is impacting and challenging the ability of information organizations to respond in ways that meet the needs of a range of underserved populations. This creates numerous tensions articulated in part below:

- Librarians want to serve those in need, but feel ill-equipped to deal with the numerous challenges that individuals often face including mental health, physical health, law enforcement, language, family challenges, and other challenges that may require addressing before librarians can offer assistance.

- Librarians often still focus on the information transaction and need as they were trained to do, while the individuals seek a more immersive and transformative experience (for example, successfully attaining health insurance, pursuing educational goals, successfully attaining access to food and shelter, getting a job, and so on). The ability of librarians to meet these often time-consuming life needs, while also trying to serve others, is a large challenge.

- The demands of the increasing number of those in substantial need—or lacking in skills and abilities for success in the twenty-first century—is constraining resources and services to the broader community. Some indicated their concern that service to the un- and underserved, though a core value to libraries, is impacting who uses, or is willing to use, the available services, resources, and facilities of public libraries.

- The growing disparities in income, opportunities, and education manifest early (for example, Pre-K, in schools), can continue into adulthood, and is witnessed in a range of ways in libraries—for example, literacies (basic, information, civic), digital readiness, workforce skills. The cycle is exceedingly difficult to break, and is a constant presence in the provision of information services and resources as librarians seek to “meet users where they are.”

The tension between the growing gaps, wanting to help those with acute needs, not having the resources or skills to, and questioning whether this is an appropriate role for libraries and librarians was a recurring theme. Further, an emergent topic was whether in the name of inclusion, focusing efforts substantially on challenged populations has led other populations who were once frequent library users (for example, families with young children, children/young adults who might otherwise use a library after school) to stop coming to or at least limiting their use of the physical library space. Even with these tensions, the prevailing sentiment from librarians was, “If not the library, then who?”

Social Innovation and Change

A common theme that emerged through the Re-Envisioning initiative was a vision of libraries and librarians as community change agents that can roughly be expressed as: Strong libraries empower their communities and enable individual change, growth, and transformation.

Though expressed in a variety of ways, participants offered a number of terms as part of this vision: innovators, entrepreneurs, disrupters, change agents, facilitators, partners, and leaders, to name some. After some discussion and expansion, participants described a vision for libraries and librarians as critical leaders of social innovation in their communities.18 By forming partnerships, for example, with health care providers, government agencies, workforce development agencies, food service agencies, faculty, research centers, telecommunications carriers, utility companies, schools, local businesses, and more, libraries are essential catalysts for creative solutions to community challenges in a wide range of areas such as health, education and learning, economic development, poverty and hunger, civic engagement, preservation and cultural heritage, and research innovation. Through leveraging trust, expertise, infrastructure, information resources, space, community centrality, cultural awareness, an appreciation of and for diversity, and other assets, libraries and librarians are the “lubricant” in their communities for innovation, entrepreneurship, and creativity. Engaging in social innovation activities also enables our organizations to provide opportunity for all in ways that they (nor any other entity) could not do on their own.

Issues and Recommendations

The Re-Envisioning process identified the above, and other, findings that have implications not just for the University of Maryland’s MLS program, but also for MLS programs in general, libraries, and professional associations. Though just the first year of the process is complete, there are a number of paths forward for LIS education. Future considerations include:

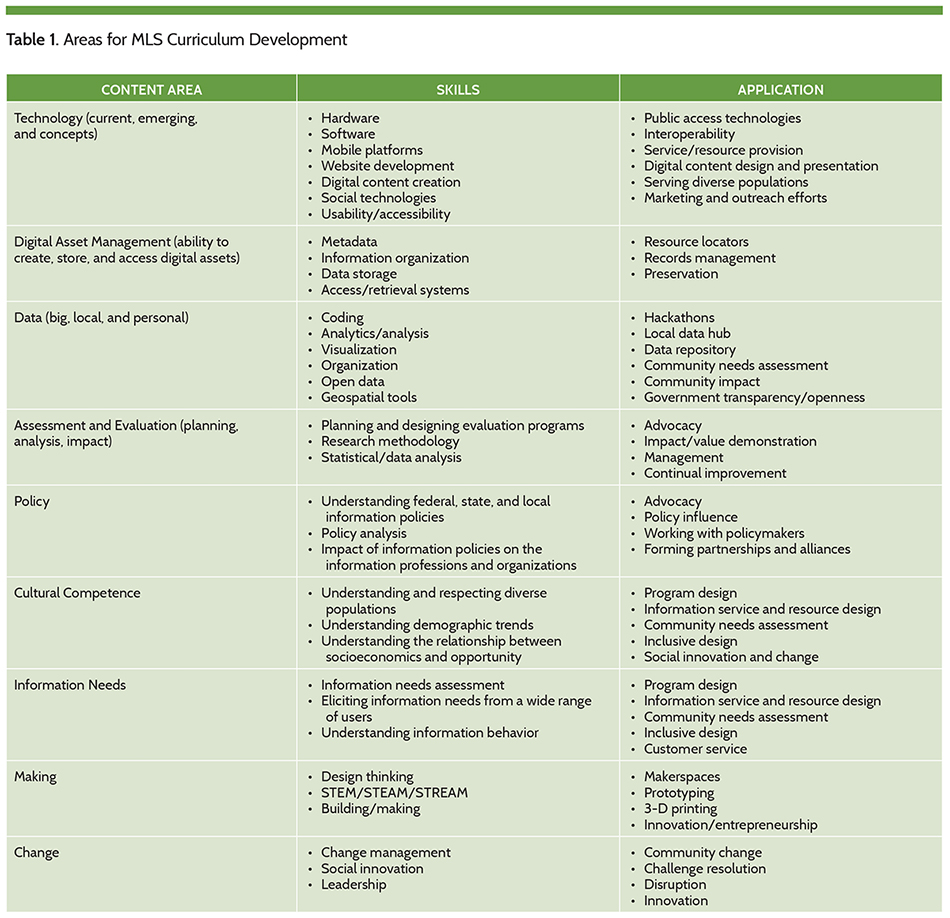

- Creating curricula that reflects current and emerging trends and realities. Adapting curriculum, learning outcomes, professional development opportunities, and recruiting to better reflect the core values and content areas identified during the re-envisioning process (see table 1). There is a need to integrate these values, skills, and competencies into all aspects of MLS education from degree requirements to ongoing professional education that occurs post-graduation. In addition, there is a need to focus library education more on creating curricula and extracurricular activities that prepare students for the realities of what libraries and librarians actually do, rather than what we think they should do based on standards and professional practices of the past. The Internet, political changes, economic changes, and other social forces have changed what libraries—especially public libraries—do. Emerging trends in technology, demographics, workforce needs, “smart” communities, and other key areas also force us to consider to what public libraries should transform—while at the same time ensuring that public libraries meet the needs and expectations of individuals and their communities.19 Courses in areas of advocacy, education, leadership, technology, data analytics, social innovation, and social justice, among others, need to become more readily available to students in library education programs. Though some may not value or buy into the shift some libraries have taken to become community hubs for education and learning, inclusion, community building, and social service provision, these activities are increasingly central to the mission of public libraries.20 Preparing students to be leaders, advocates, and social innovators—through coursework, continuing education programs, and other activities—for their institutions and their communities is necessary for the sustained health of institutions, the professional success of MLS graduates, and for ensuring opportunity for all in the communities that libraries serve.

- Engaged and qualified faculty. There are many accredited MLS programs from which students can choose. These programs are embedded in a variety of academic units, and coursework is available in multiple modes—online, in person, or hybrid. The issue in the future is less the availability of MLS education than access to an engaged and qualified faculty and leadership that: (1) values the MLS degree as part of the academic unit; (2) seeks to leverage the increasingly diverse disciplines represented on faculties (for example, computer science, information management, human-computer interaction, learning sciences) to benefit MLS programs; and (3) is connected to the profession and professionals.

- Research that informs. Scholars also have important contributions to make to the MLS degree. For a field in which so much of the work is professional in nature, it is ironic that research about MLS graduate education has been fairly limited.21 Faculty charged with preparing future librarians could be much more committed to researching, evaluating, and creating innovative approaches to the formal and informal education of MLS students. We need to better understand the service context of public libraries, the communities that public libraries serve, the needs (not just information) of individuals who use (and do not currently use) public libraries, and the extent to which our programs and courses prepare graduates to become public library professionals and leaders. By also studying the public library as a social, learning, engagement (and other dimensions as identified as part of the Re-Envisioning the MLS initiative) institution, we can use that knowledge to enhance our MLS programs and practice.

- Professional organization support for library education. Professional organizations need to increase their focus on how well they are supporting library education programs in preparing their students for the needs of today and tomorrow. ALA accreditation, for example, is a cumbersome process for institutions and the standards themselves are slow to adapt. Even though ALA has recently revised the accreditation standards, the revision and review process needs to be more agile. Beyond accreditation, the preparation of library school students and young professionals for success in the field is a place in which professional organizations could contribute even more to the long-term health of professionals through mentoring, networking, and continuing education.

- Rethinking hiring expectations. Many new library graduates are limited in the number of jobs (and here we reference only entry-level positions) for which they can qualify because organizations are crafting positions that require a set of qualifications that new graduates simply cannot meet, most typically multiple years of experience. A tight job market has created a “buyer’s market” but this does not mean that employers should shut out new graduates. As we learned from discussions with recent graduates and alumni, they will, and are, going elsewhere—in some cases leaving the profession entirely. A library may benefit in the short term from hiring only experienced librarians but this strategy will impact our libraries in the long term if no, or few, new graduates are brought into the fold. Employers may better serve their own institutions and the field as a whole by looking to fill positions with a greater balance of experience, innovation, and new graduates.

- Co-Creation, not Confrontation. Underlying the discussions and site visits with librarians was the sense that library schools, in part,

were not providing the kinds of graduates they needed for today’s (and tomorrow’s) libraries. But this discussion always seemed a bit “you [iSchools, MLS programs] and us [libraries, professionals]” in its tone. The future rests with strong collaborative development of our curriculum—from courses to experiential learning. Co-creation of curriculum and professional practice opportunities can yield great synergies:

public libraries would have access to new professionals who meet their needs and the needs of their communities, MLS programs would remain current, and students would have access to relevant leaning experiences and knowledge. The language of “we” is powerful and necessary and through it we all benefit.

The qualities that make libraries so unique and important in their communities can be summarized in four verbs: inform, enable, equalize, and lead.22

These attributes of libraries can also serve as guiding principles for rethinking library education and how we prepare and support students for their careers.

Individual public libraries are often most impressive in the speed with which they can adapt to changing community needs. Library education, professional organizations, employers, and scholars have to become similarly adept at the changing expectations for and capacities of libraries. Horrigan notes, public libraries are at a crossroads.23 So too is MLS education. As the Re-Envisioning the MLS project shows, there are a number

of paths forward for improving the entire process of educating new library professionals to be ready to contribute to their organizations, communities, and society as soon as they graduate. This will require, however, the conviction to make bold changes to ensure the continuing relevance of our field. Our students, our professionals, our organizations, and our communities are all depending on it.

References

- American Library Association, “State of America’s Libraries Report 2014,” accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- Amy K. Garmer, Aspen Institute, “Rising to the Challenge: Re-Envisioning Public Libraries,” accessed Dec. 13, 2015; American Library Association, “Trends Report: Snapshots of a Turbulent World,” accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- John B. Horrigan, Pew Research Center, “Libraries at the Crossroads,” accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- Paul T. Jaeger, et al., Public Libraries, Public Policies, and Political Processes: Serving and Transforming Communities in Times of Economic and Political Constraint (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014); John Carlo Bertot, et al., 2013 Digital Inclusion Survey: Survey Findings and Results. (College Park, Md.: Information Policy & Access Center, University of Maryland College Park, 2014); Paul

T. Jaeger, et al. Libraries, Human Rights, and Social Justice: Enabling Access and Promoting Inclusion (Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015); Kim M. Thompson, et al., Digital Literacy and Digital Inclusion: Information Policy and the Public Library (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014). - John Carlo Bertot, et al., “Re-Envisioning the MLS: Findings, Issues, and Considerations” (College Park, Md.: College of Information Studies, 2014), accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- Samuel Rothstein, “Why People Really Hate Library Schools: The 97-Year-Old Mystery Solved at Last,” Library Journal 110, no. 6 (April 1985): 41–48.

- April Bohannan, “Library Education: Struggling to Meet the Needs of the Profession,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 17, no. 4 (1991): 216–19.

- André Cossette, Humanism and Libraries: An Essay on the Philosophy of Librarianship (Duluth, Minn.: Library Juice, 2009); Michael Gorman, The Enduring Library: Technology, Tradition, and the Quest for Balance (Chicago, Ill.: ALA Editions, 2003); Richard J. Cox, The Demise of the Library School: Personal Reflections on Professional Education in the Modern Corporate University (Duluth, Minn.: Library Juice, 2010); Boyd Keith Swigger, The MLS Project: An Assessment After Sixty Years (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield).

- Juris Dilevko, The Politics of Professionalism: A Retro-Progressive Proposal for Librarianship (Duluth, Minn.: Library Juice Press, 2009).

- Annoyed Librarian, “Okay, Who Cares if Library School is Easy,” Annoyed Librarian blog, Oct. 25, 2010, accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- Emily Weak, “Do Not Go to Library School. Librarianship is a Dying Profession,” Hiring Librarians blog, Jan. 14, 2014, accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- American Library Association, Library Education Task Force, “President’s Task force on Library Education Final Report,” accessed Dec. 13, 2015; American Library Association, “ALA’s Core Competencies of Librarianship,” accessed Dec. 22, 2015; American Library Association, Committee on Accreditation of the American Library Association, “Standards for Accreditation of Master’s Programs in Library and Information Studies,” accessed Dec. 13, 2015; Simmons College, “Envisioning Our Future and How to Educate for It,” (2015), accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- Alexis McCrossen, “One More Cathedral” or “Mere Lounging Places for Bummers? The Cultural Politics of Leisure and the Public Library in Gilded Age America,” Libraries and the Cultural Record 41, no. 2 (Spring 2006): 169–88; Jean L. Preer, J. L. (2006). “Louder Please: Using Historical Research to Foster Professional Identity in LIS Students,” Libraries and the Cultural Record, 41, no 4 (2006): 487–96.

- Andrew Dillon and April Norris, “Crying Wolf: An Examination and Reconsideration of the Perception of Crisis in LIS Education,” Journal of

Education for Library and Information Science, 46, no. 4 (Fall 2005): 280–98. - Stuart A. Sutton and Nancy A. Van House, “The Panda Syndrome II: Innovation, Discontinuous Change, and LIS Education,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 40, no. 4 (Month or Season? 1998): 247–60.

- Paul T. Jaeger, “Looking at Newness and Seeing Crisis? Library Discourse and Reactions to Change,” Library Quarterly 82, no. 2 (April 2012): 289–300.

- Jon Bowman, KWGN Colorado, (2015, July 7). “Denver Public Library Hires Social Worker.” KWGN Colorado, July 7, 2015, accessed Dec. 13, 2015; Mark Jenkins, (2014, August 27). “D.C. Adds a Social Worker to Library System to Work with Homeless Patrons, Washington Post, Aug. 27, 2014, accessed Dec. 13, 2015; Scott Shafer, “Urban Libraries Become De Facto Homeless Shelters,” NPR, April 23, 2014, accessed Dec. 13, 2015; Patrice Chamberlain, P. (2015, March 17). “Summer Meal Programming at the Library,” Public Libraries Online, March 17, 2015, accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- James A. Phills, et al., “Rediscovering Social Innovation,” Stanford Social Innovation Review (Fall 2008), accessed Dec. 13, 2015.

- American Library Association, “Trends Report: Snapshots of a Turbulent World”; Horrigan, “Libraries at the Crossroads. Pew Research Center.”

- Lynn Westbrook, “I’m Not a Social Worker: An Information Service Model for Working with Patrons in Crisis,” Library Quarterly, 85, no. 1 (Month or Season? 2015): 6–25.

- Cox, The Demise of the Library School:

- Bertot et al., “Re-Envisioning the MLS: Findings, Issues, and Considerations.”

- Horrigan, “Libraries at the Crossroads.”

Tags: MLIS Students