The Importance of Teaching Adult Services Librarians to Teach

JESSICA A. CURTIS is an Adult Services Librarian at the Westerville (OH) Public Library. Contact Jessica at jcurtis@westervillelibrary.org. Jessica is currently reading The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World by Andrea Wulf.

“But, librarians aren’t teachers.” This was one of the first (and most common) comments I encountered when I began my research. “Degree-wise, yes. But,” I asked, “are they instructors?” Do most libraries (read this as librarians) have to walk someone through a process, whether it be how to download and use an app, reserve a book or a room, or access and use library databases? What about programs and classes? Most libraries today are offering a variety of choices to their adult communities: help with résumés, genealogy, technology. Name a topic, and some library in the United States is probably offering a class or program. Do these all count as teaching? Of course they do.

Librarians and library staff are undoubtedly the link that brings many resources and skills to patrons. Marketing, physical location, and well-designed websites play an enormous part in raising awareness and interest, but many, many adult users will not venture towards the unknown without a guide. And that guidance, or instruction, is teaching.1

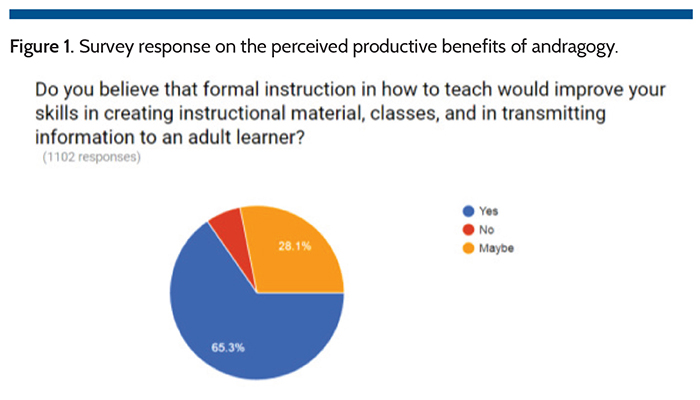

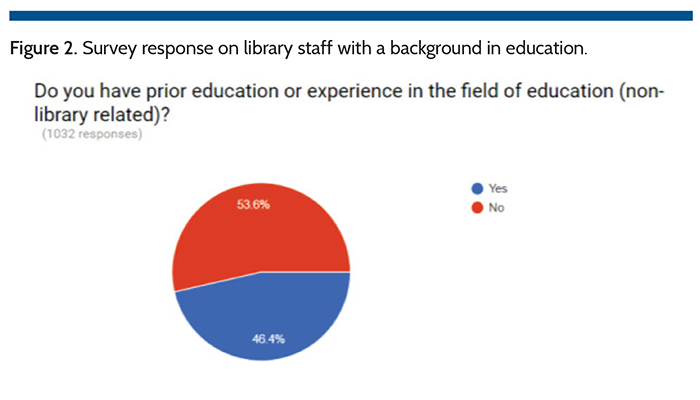

A survey of 1,115 librarians across the United States showed that library staff are well aware of this, with only 6.5 percent saying that they would not benefit from formal instruction on how to teach.2 As of yet, pedagogy (the science of teaching) and andragogy (the science of teaching adults) are not an integral part of most, or even many, American Library Association (ALA) library programs. Ask any librarian with an education background—and there are a lot out there (46.4 percent of those surveyed)—and that librarian will say that a foundation in learning theory and instruction has an enormous impact on not only the day-to-day work in the library, but also its classes and programs.3 Once they’re on the job, librarians without a similar background often recognize this lack and endeavor to fill in their knowledge gap with continuing education, seeking ways to improve their skills so that those they serve get the most out of what they’re offering.

So what can be gained from a familiarity with learning theory? Listed here are just some of the more basic tenets most often involved in teaching adults. A simple awareness of these factors can help those creating programming, training staff, or simply walking a patron through a process or new skill, by increasing the chance that the information will “stick.”

Motivating Factors

In the 1980s, Malcolm Shepard Knowles listed a series of considerations, or motivating factors, that separate adult learners from children and adolescents.4 These considerations have been added onto and expounded upon in the fields of education and even psychology as more researchers delve into the inner workings of adult learners.

The first consideration is that adults are often self-directed learners. In a library context, that means that they did not have to come to the class or ask a librarian for help. They chose to do so. Another factor is that adults aren’t blank slates. They come into any learning environment with a lifetime of accumulated knowledge and experiences that can directly impact their learning experience. Adult learners are also goal-oriented.5 Ask an adult learner why they are there at that moment, and they will be able to tell you what they want to know, or rather, what they want to accomplish with the knowledge they hope to gain. Being aware of the gap in their knowledge is another adult characteristic. One example of this is seniors’ approach to smartphones. They’ve seen what their family and friends can do with it, and they know that they can’t do the same. The next factor is that class, even a free one, is secondary to everything else in their lives.

Emotional, physical, and social realities also serve as motivators. What emotional response might a seventy-year-old have sitting in a technology class filled with people in their twenties? What about the reverse? Even the way instructors phrase things to those they’re helping can immediately affect emotional motivators. Physical factors are an important consideration for any age. How are the chairs? The acoustics? The room temperature? All of these and more can factor into the attendee’s decision whether or not to come to another class. Finally, how social the program is, or not, can be the focus of attention for many an attendee. Some people come simply for the social aspect. Others will avoid any class or event that has what they consider too many people.

Sensory Learning Styles

Individuals with different preferences for how they receive and interact with what they need to learn are said to have different sensory learning styles. An individual’s preference for either aural (they need to hear it), visual (they need to see it), or kinesthetic (they need to physically interact with it), can make the difference as to the retention of and interest in the subject matter.6 For example, I am a kinesthetic learner. This means that if an instructor wants me to remember how a phone works, they will have to let me try it out. Aural learners will often want things explained out loud, even if there is a book or handout that says the same thing. Visual learners will need the words to be written down or the process to be demonstrated before they feel that they have “learned.”

Instructors need to be especially careful when it comes to sensory learning, in that most will naturally gravitate towards their own preference when instructing others. Any one-on-one situation can be geared towards an individual’s preference, but most multi-person classes and programs can be built to accommodate all styles.

Generational Learning Styles

There are currently five adult generations active in most communities: Baby Boomers, Generation X, Generation Y, Millennials, and Generation Z. All of these generations have been found to relate very differently to learning situations.7 This can make an enormous difference when a Millennial, whose generation leans towards self-directed group-led learning, decides to create a class geared towards Boomers, who typically are seeking a “traditional” classroom setting where the teacher is the authority and the purveyor of knowledge. This also impacts individual instruction, as the librarian has the potential to tailor each interaction to suit learning styles.

Instructional Design

Deliberate thought should also be given to how a class is constructed. “Failing to plan is planning to fail,” as the proverb goes. This may not be strictly true when it comes to library classes and interactions, but planning harms nothing. In fact, writing down a plan can help when pitching ideas to the powers-that-be and can serve as a guide for those might need to substitute or take over a class or program.

Instructional design is used to answer fundamental questions about a class or program. Effective Adult Learning: A Tool-kit for Teaching Adults lists six common design factors:

- What is the general theme or topic?

- What are the goals?

- What is the central question?

- How will participants interact with the material in class to reach the goal?

- What resources will the instructor need to accomplish the goal?

- How will the library assess whether or not people have learned anything?

Answering these kinds of questions at the outset can help instructors and administrators create realistic goals and make the most of their time and resources.8

Conclusion

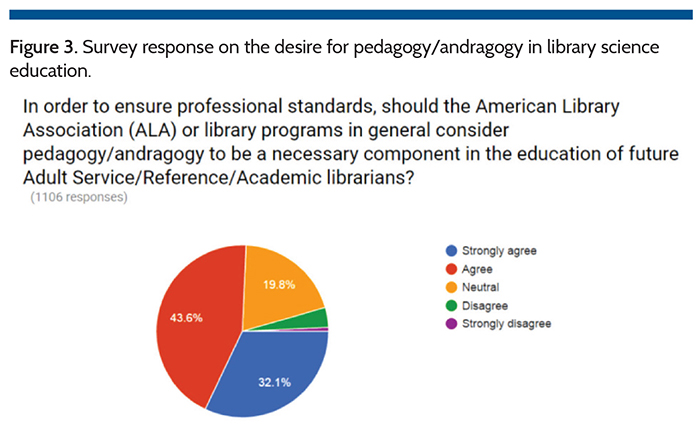

Instruction is an essential aspect of modern library services to adults. The theories and methods listed here are just a sample of the wealth of knowledge available on the subject. I, and the majority of survey respondents, urge the sixty ALA-accredited schools to include andragogy in their related curriculum so as to equip new librarians with the skills that the profession now demands.9 Librarians in the field should make use of the numerous books, articles, conferences, webinars, and other continuing education opportunities available to them to learn and then utilize the many philosophies and techniques that science and experience have provided. This effort benefits not just the librarians who learns the skills, but also the libraries and the communities that they serve.

References

- Char Booth, Reflective Teaching, Effective Learning: Instructional Literacy for Library Educators (Chicago: ALA Editions, 2011), xv–xvi.

- Jessica A. Curtis, “Teaching and Instruction Survey,” last modified Jan. 2017, accessed Jan. 1, 2017, . Refer to Figure 1.

- Ibid. Refer to Figure 2.

- Sharan B. Merriam, “Andragogy and Self-Directed Learning: Pillars of Adult Learning Theory,” in “The Update on Adult Learning Theory,” ed. Sharan B. Merriam, special issue, New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education 2001, no. 89 (Spring 2001): 4–5.

- Michael Eisenberg, “Information Literacy: Essential Skills for the Information Age,” DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Science 28, no. 2 (Mar. 2008): 43.

- Robin Neidorf, Teach Beyond Your Reach: An Instructor’s Guide to Developing and Running Successful Distance Learning Classes (Chicago: Information Today, Inc., 2012), 51–53.

- Julie Coates, Generational Learning Styles (River Falls, WI: LERN Books, 2007).

- Effective Adult Learning: A Toolkit for Teaching Adults (Northwest Center for Public Health Practice at the University of Washington School of Public Heath, 2014), 22–25, accessed Aug. 23, 2017.

- Curtis, “Teaching and Instruction Survey.” Refer to Figure 3.

Resources

Nicole A. Cooke, “Becoming an Andragogical Librarian: Using Library Instruction as

a Tool to Combat Library Anxiety and Empower Adult Learners,” New Review of Academic Librarianship 16, no. 2 (2010): 208–27.

Lauren Hays, “Teaching Information Literacy Skills to Nontraditional Learners,” Kansas Library Association College and University Libraries Section Proceedings 4, no. 1 (2014).

“Learning Theories,” Library Instruction Round Table, American Library Association, accessed Dec. 13, 2016.

Megan Oakleaf and Amy VanScoy, “Instructional Strategies for Digital Reference: Methods to Facilitate Student Learning,” Reference & User Services Quarterly 49, no. 4 (Summer 2010): 380–90.

Je Toister, “Instructional Design Essentials: Adult Learners,” Lynda.com, 45:34, Sept. 23, 2014.

Hsin-yi Sandy Tsai et al. “Getting Grandma Online: Are Tablets the Answer for Increasing Digital Inclusion for Older Adults in the U.S.?,” Educational Gerontology 41, no. 10 (2015): 695–709.

Tags: andradogy, instruction, pedagogy