E-Government: Service Roles for Public Libraries

Public librarians now assist many patrons with federal, state, and local government agencies’ services that have moved almost exclusively online––with increases in online services occurring since the passage of the E-Government Act of 2002.1 Persons with limited or no Internet access, or persons who need assistance using technology or understanding and reading forms, rely on public libraries to access e-government services.2 In results from the 2009–2010 Public Library Funding and Technology Access Survey (PLFTAS), two-thirds of public libraries reported being the only provider of free public access to computers and the Internet in their communities and 78.7 percent of libraries reported they provide assistance to patrons applying for or accessing e-government services.3 These e-government services include, but are not limited to, the following:

- access to and assistance navigating e-government websites:

- assistance filling in forms and sending e-mails related to obtaining forms;

- help writing employment letters and résumés, completing employment and unemployment applications, and searching employment databases;

- creating e-mail accounts; and

- locating government information such as government assistance and grants, Medicare benefits, immigration and naturalization regulations, tax forms, hunting and fishing licenses, and so on.4

In addition to these services, a growing number of public libraries (20.5 percent) reported partnering with government agencies.5 Also, patrons expect that public libraries provide free Internet access and trust library staff members to assist them in the use of e-government services.6 With the growth in e-government expected to continue, defining e-government service roles for practical application in public libraries may assist libraries in planning for the provision of these services and better understanding the resources that would be needed to offer such services.

This article does not contain a formal literature review of e-government and public libraries, but several resources are available from the American Library Association’s (ALA) E-government Toolkit. However, a brief review of the term “service roles” assists this discussion. Service roles were introduced nationally in a 1987 Public Library Association (PLA) book, Planning and Role Setting for Public Libraries: A Manual of Options and Procedures, which describes what a library is trying to do, whom the library is trying to serve, and what resources the library needs to achieve these services.7 Two PLA revisions reflected the shift to Internet-enabled service roles that are further expanded upon in McClure and Jaeger’s Public Libraries and Internet Service Roles: Measuring and Maximizing Internet Services.8

The e-government service roles presented here are based on two studies conducted in Florida public libraries in 2009 and 2010.9 Through this research, study team members reviewed PLFTAS data and conducted interviews with selected Florida and other public librarians to define levels of e-government service and classify the services into a framework. Additional discussion of the methods may be found in the reports available at the Information Management and Policy Institute’s website. Based on informal discussions with other public librarians outside the state of Florida, the study team believes that other states’ public libraries perform very similar services due to the volume of e-government and public libraries literature coupled with PLFTAS data. In fact, both the ALA E-Government Services Subcommittee and Florida E-government Working Group reviewed a draft of the service roles and provided feedback, helping to better generalize the service roles. The e-government service roles introduced here provide public libraries with an opportunity to better plan, implement, and meet community expectations regarding e-government services.

E-Government Service Roles

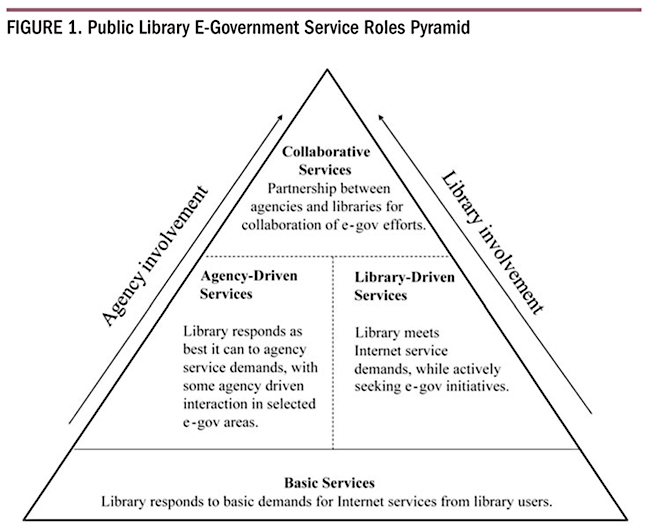

The 2009 and 2010 studies conducted by the study team at the Information Institute led to four potential e-government service roles for public libraries: (1) Basic Services, (2) Library-Driven Services, (3) Agency-Driven Services, and (4) Collaborative Services. Figure 1 provides a view of the relationships between agencies and libraries in the provision of e-government services. The figure depicts increases in both public library and agency involvement with arrows pointed toward the top of the pyramid where, in the Collaborative Services role, a partnership between the two occurs.

The pyramid structure reflects the fact that fewer public libraries meet the Library-Driven and Collaborative Services roles criteria, according to PLFTAS data. In addition, all services build upon the oneto-one, as needed interactions between a library user and a librarian, which constitute the Basic Services role.

Basic Services

The Basic Services role of public library e-government services is comprised of services many public libraries already provide. Despite the fact that many libraries do not categorize these services as e-government services per se, the majority of public libraries report assisting patrons with applying for or accessing e-government services (78.7 percent of PLFTAS respondents).10 In addition, 88 percent stated they helped users understand and use government websites.11 These types of services comprise the Basic Services role.

Public libraries assist in e-government service provision by meeting the basic demands for Internet services from library users, which may include accessing, navigating, or filling out e-government websites and forms, and also some computer assistance, such as general training or obtaining and using e-mail accounts. These services require nearly no planning beyond the Basic Services role of public libraries providing Internet access and assistance. Also, these services usually occur on a one-to-one, as-needed basis between a library user and a librarian.

Other basic services include the emergency preparation and response services provided on the fly by public libraries. Several public libraries indicated they assist residents during and after disasters, including serving as distribution centers for supplies and information, providing shelter and physical aid, and also providing normal library services for displaced users.12 Similar to the other e-government services offered in the Basic Services role of public library e-government services, public libraries offer these emergency services in response to demand from users, rather than as a result of active planning. The library resources, training, and support needed to be successful in the Basic Services role are minimal. Although most study participants worked in areas impacted by hurricanes in the U.S. Gulf Coast, disasters both manmade and natural could occur anywhere in the United States and aspects of the Basic Services role may be useful to many public libraries regardless of the specifics of a disaster. The Basic Services role is implied in each of the subsequent service roles (those higher up the pyramid in figure 1).

Library-Driven Services

Some public libraries take a more proactive approach to the provision of e-government services than just meeting on-demand user needs. In the PLFTAS, 8.9 percent of responding public libraries reported that they offer classes regarding the use of government websites, programs, and electronic forms.13 These examples indicate additional efforts from the library and represent the Library-Driven E-government Services role, which also include:

- offering training classes regarding the use of government websites, programs, and electronic forms;

- collecting and disseminating informative pamphlets on e-government services;

- creating Web 2.0 tools to disseminate information; and

- becoming an emergency information hub.14

These services go farther than simply helping residents on an as-needed basis to build services that better organize e-government service provision for library users.

Public libraries have proactively created and offered services that include:

- purchasing laptops dedicated for e-government services;

- increasing wireless connectivity to utilize e-government services;

- providing e-government assistance through one-on-one appointments;

- creating and delivering e-government or basic computer skills workshops for adults;

- building a web portal with government information;

- making handouts with government information; and

- developing online multimedia tutorials.15

In some cases libraries built web portals and tools to assist residents in the navigation and use of e-government services with limited interaction from government agencies (For examples, see http://gethelpflorida.org and www.njstatelib.org/Research_Guides/US_Government).

A Web Services model of e-government service provision, such as those two examples, could include active involvement from government agencies. However, when the Web Services do not include any collaboration or coordination with government agencies, they fall within the Library-Driven Services role of public library e-government services, no matter how sophisticated these services may be.

In response to disasters, proactive libraries will take additional steps to be prepared to disseminate print and electronic information concerning disaster-related e-government services. Some public libraries may serve as emergency information hubs that will offer a host of services to streamline disaster response, such as charging of electrical equipment; providing access to computers, copiers, fax machines, Internet access, Wi-Fi, office supplies, phones, printers, and scanners; and offering electricity, furniture, light, and air conditioning.16

The distinguishing elements between the Library-Driven Services role and the Basic Services role are the additional planning and associated costs required to offer these proactive services. These services do not match the definition of the Collaborative Services role because of the minimal or no collaboration or coordination between government agencies and the libraries. Similarly, Agency-Driven Services exist with no or limited amounts of collaboration or coordination between government agencies and the libraries.

Agency-Driven Services

The Agency-Driven Services role of public library e-government services, as the name indicates, describes public libraries that act in a reactive stance to the demands of government agencies. A library may respond the best it can to agency service demands. The distinguishing element of this service role from the Library-Driven Services role is a lack of impetus from the library to implement these services. Types of services may include:

- agencies providing personnel to assist library users;

- agencies training librarians on issues related to e-government such as eligibility for various government benefits and services;

- agencies requesting space in libraries for meetings and trainings;

- agencies providing and maintaining information kiosks in the library; and

- agencies referring customers to libraries for assistance via the Basic Services role.

In most instances, public libraries falling into this category continue to offer services related to the Basic Services role, remain reactive to the demands of government agencies and residents, and are not proactive in volunteering to offer additional e-government services.

Public libraries incur fewer costs from agency driven services than library driven services. However, some expenses do relate to the library resources, training, and support depending on the services offered. Examples of this service role include the Social Security Administration’s program to encourage citizens to retire online and visit their public libraries, with the help of Chubby Checker and Patty Duke; the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) utilizing the space, librarians, and resources of many public libraries after hurricanes; Data.gov; and several others.17 In most instances, these activities are beyond the control of the public library; however, these agency programs and actions do have an effect on library resources, training, and support.

Collaborative Services

The Collaborative Services role differs from the Basic, Library-Driven, and Agency-Driven Services roles in that it requires the active partnership between government agencies and public libraries. Findings in the PLFTAS indicate that 20.5 percent of public libraries say they are partnering with government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and others to provide e-government services.18 Partnering in the Collaborative Services role includes activities that result in clear products developed during multiple meetings between the library and government agencies and activities that go beyond those listed in the Library Driven and Agency Driven Services roles.

Low levels of collaborations were indicated in interviews with public librarians, and these included distributing handouts provided by government agencies and providing space for their trainings. Also, posting links to e-government websites or creating multimedia tutorials may be time-intensive for library staff and costly burdens on library resources; however, these activities lack formal coordination with agencies and thus do not fall into the Collaborative Services role. Hopefully, more agencies will see the benefits of collaborating with the librarians serving the public and an increase will occur in Collaborative Services. So far, examples of these proactive collaborations that improve e-government provision include:

- an active library liaison that meets with local, state, and federal governments on a regular basis;

- an integrated and collaborative environment among libraries, governmental offices, and community agencies towards provision of e-government; and

- libraries and agencies coproducing instructional materials and educational programs.

Despite the indications from the PLFTAS and the de facto collaboration regarding all public libraries providing Internet access and government agencies sending residents to them, the Collaborative Services role of public library e-government services includes services where sustained dialogue occurs between government agencies and public libraries.

One stellar example of a success story with agency and library collaboration is the partnership between the Alachua County Library District (ACLD), the Florida Department for Children and Families (DCF), the Partnership for Strong Families (PSF), the Casey Family Program, and approximately thirty social service agencies working together to create and operate the Library Partnership, a Neighborhood Resource Center. The partnership’s goal is to strengthen families through addressing self-sufficiency, family support and child welfare, and health and safety. This partnership allows the librarians to fine-tune collections, services, and other resources to complement the social service providers and meet the needs of clients visiting the library. The project benefits from (1) multiple agencies collaborating toward one goal, (2) the library seeking a store location in the same geographic region of the county as the agencies, and (3) the agencies’ knowledge of the public library’s previous e-government efforts. The co-location of multiple government services provides an exemplar for future library-agency partnerships, but this opportunity would not have occurred without active library leadership that was both present at county discussions and previously active in the provision of e-government services.

Just as a public library can serve as a place for collaboration between other government agencies and library staff at all times, during disaster response the library could serve as the Cultural Organizations Liaison.19 Duties related to the disaster response aspects of the Collaborative Services role of public library e-government services include assisting government agencies and their staff in disaster response and establishing a single point of emergency communication contact with emergency management.

By permanently and collaboratively sharing space with government agencies and having regular dialogue among all partners, library staff and government agency partners may provide coordinated and complementary services to meet residents’ e-government needs. Although the ACLD partnership branch example is for physical services, government agencies and public libraries also may coordinate on building Web 2.0 tools to assist residents beyond the brick and mortar facilities with services such as virtual reference. The extra coordination in the developing, hosting, and other activities separate these types of Web 2.0 development from those that would strictly involve libraries alone and fall within the Library-Driven Services role. The Collaborative Services role distinguishes its associated services from other e-government service roles by including active partnerships with sustained dialogue between government agencies and public libraries. This mix of agency and library involvement places the Collaborative Services role of public library e-government services at the pinnacle of a pyramid structure of e-government service roles (see figure 1).

Next Steps for Expanding E-Government Service Roles

Although several public libraries reach beyond the Basic Services role, many do not yet do so. The purpose of outlining the e-government service roles is to assist libraries in doing so. State libraries or other funding agencies may develop incentives and rewards for libraries to take on more advanced e-government services. Without such incentives, funding these additional e-government services remains an obstacle for public libraries in growing beyond the activities described in the Basic Services role. Offering training and education to public librarians about these service roles may be a first step in assisting libraries to take on additional e-government activities. This training could be offered by state library agencies, PLA, regional library cooperatives, and/or Library and Information Studies (LIS) schools via continuing education courses. Developing regional models where some libraries provide one level of service and refer users to other libraries providing more extensive e-government services is another potential strategy for expanding e-government service provision in public libraries.

Another important next step in the development of these service roles is to further investigate the actual costs associated with the provision of e-government. Also, research is needed to understand better the resources and organizational structures that are required to implement these roles. By identifying the benefits, impacts, and outcomes from providing the services specific to the e-government service roles, public libraries can better communicate and synthesize to specific stakeholder groups, and especially local and state government officials, the value of public libraries providing these services. Given the extent to which these services are being provided already, it may be useful to ascribe a dollar amount to the services to demonstrate how public libraries are assisting all government services.

Perhaps, the state, local, and federal agencies offering e-government services could improve the dialogue and coordination between their e-government services and public libraries assisting residents by holding statewide conferences. Such conferences would be dedicated to e-government and public libraries and could include many of the parties involved in the provision of e-government. In addition, several public libraries and agencies could present their experiences and lessons learned from e-government service provision at a national conference to lead to new models of resource sharing and best practices.

Using E-Government Service Roles in Your Library

In addition to efforts at state, regional, or national levels, individual public libraries can expand their levels of e-government service provision. Major goals of this article are to (1) assist libraries in understanding what e-government services are; (2) help librarians identify which e-government services they already provide and which they could provide with varying levels of time, money, and other resources; and (3) encourage libraries to implement more proactive and coordinated efforts in their communities.

Libraries can use the examples provided in this paper to identify which e-government services they already provide and their current level on the Service Role pyramid. Then, through strategic planning meetings, the libraries can determine what other e-government services they should provide, depending on local resources, support, and community needs. During this process, libraries specifically should consider regional and other local libraries’ efforts and how the libraries can join forces to maximize e-government service provision while minimizing labor and resource costs. For example, a municipal library might investigate what egovernment services are being offered at a nearby county library system and contact that library to see how those efforts could be expanded or modified to meet the unique needs of the municipality. Then, the municipal library could coordinate with the county library to provide additional e-government services that the municipal library otherwise might not be able to provide its users, given limited financial and other resources.

The point of the e-government service roles is not to intimidate librarians with far-reaching goals, but to offer (1) longterm goals to accomplish, (2) immediate opportunities for e-government service expansion, and (3) steps along the way from the libraries’ current level to their desired level of e-government service provision. These efforts at expansion can be facilitated not only through understanding e-government service roles, but also through use of practical tools such as the ALA E-government Toolkit, service role manuals, and examples of libraries already achieving high levels of e-government service provision, like the Alachua County Library District.

Finally, it is essential that public libraries and state library agencies engage in ongoing dialogue with local, state, and federal government agencies about the role of libraries in the provision of e-government services. There is a clear need to better coordinate the services and activities of public libraries with these government agencies such that services are not duplicated and that resources among the various libraries and government agencies are leveraged as much as possible. When public libraries and government agencies coordinate and jointly plan e-government services, local community residents received much improved egovernment services.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Florida Division of Library and Information Services, all the librarians who participated in the studies, as well as the ALA E-Government Services Subcommittee and Florida E-government Working Group for reviewing the e-government service roles.

REFERENCES

- John C. Bertot et al., “Public Access Computing and Internet Access in Public Libraries: The Role of Public Libraries in E-Government and Emergency Situations,” First Monday 11, no. 9 (2006), n.p., accessed Apr. 26, 2011, www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1392/1310.

- Charles R. McClure and Paul T. Jaeger, Public Libraries and Internet Service Roles: Measuring and Maximizing Internet Services (Chicago: ALA, 2009).

- John C. Bertot et al., 2009–2010 Public Library Funding and Technology Access Survey: Survey Results and Findings (College Park, Md.: Center for Library and Information Innovation, 2010), 10, accessed Apr. 26, 2011, www.ala.org/plinternetfunding.

- Charles R. McClure et al., Needs Assessment of Florida Public Library E-Government and Emergency/Disaster Management Broadband Services (Tallahassee, Fla.: Information Use Management & Policy Institute, College of Communication & Information, Florida State University, 2009), accessed Apr. 26, 2011, http://ii.fsu.edu/Research/Projects/All/Projects-from-2009-to-1999/2009-Project-Details.

- Bertot, 2009–2010 Public Library Funding, 10.

- Amelia N. Gibson, John C. Bertot, and Charles R. McClure, “Emerging Role of Public Librarians as E-Government Providers,” Proceedings of the 42nd

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Los Alamitos, Calif.: IEEE Computer Society, 2009), 1–10. - Charles R. McClure et al., Planning and Role Setting for Public Libraries: A Manual of Operations and Procedures (Chicago: ALA, 1987).

- McClure and Jaeger, Public Libraries and Internet Service Roles, 2.

- Charles R. McClure et al., Needs Assessment of Florida Public Library; Charles R. McClure et al., Pasco County Public Library Cooperative E-Government Services in Public Libraries, 2010: Final Report of Project Activities (Tallahassee, Fla.: Information Use Management & Policy Institute, College of Communication & Information, Florida State University, 2010), accessed Apr. 26, 2011, http://ii.fsu.edu/content/view/full/35680.

- Bertot, 2009–2010 Public Library Funding, 10.

- Ibid.

- Lauren H. Mandel et al., “Helping Libraries Prepare for the Storm with Web Portal Technology,” Bulletin of ASIS&T 36, no. 5 (2010), 22–26.

- Bertot, 2009–2010 Public Library Funding, 10.

- Information Use Management and Policy Institute, “Hurricane Preparedness and Response for Florida Public Libraries,” Florida State University College of Communication and Information, accessed July 21, 2010, http://hurricanes.ii.fsu.edu/4infoHub.html.

- Charles R. McClure et al., Pasco County Public Library Cooperative E-government Services.

- Information Use Management and Policy Institute, “Hurricane Preparedness and Response for Florida Public Libraries.”

- Charles R. McClure et al., “Public Libraries in Hurricane Preparedness and Response,” in Public Libraries and the Internet: Roles, Perspectives, and Implications, ed. John C. Bertot, , Paul T. Jaeger, and Charles R. McClure (Santa Barbara, Calif.: Libraries Unlimited, 2011), 75–90.

- Bertot, 2009–2010 Public Library Funding, 10.

- Information Use Management and Policy Institute, “Hurricane Preparedness and Response for Florida Public Libraries.”

Tags: e-government