Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action Applying the OODA Loop Concept to Libraries

Jim Jatkevicius is the Adult Services Librarian for Forest Grove (OR) City Library. Contact Jim at jimj@wccls.org. Jim is currently reading Don’t Skip Out on Me: A Novel by Willy Vlautin.

As we know, technology continues to redefine how we perceive the communities in which we participate. The perils and promises of machine learning shape our world around us in knowable ways. Social media allows us to participate at arm’s length as never before. It has transformed how we form and nurture our affinity groups so that we experience increasingly more closed systems that reluctantly absorb outside information. The world has become more entropic and arguably less connected to traditional institutions because of social media’s absorbing and disruptive influences. It has become hard for public institutions such as libraries to build upon traditional patron allegiances and support, and more perilous to depend solely on them. Moreover, in our attempts to nurture these allegiances, we struggle to comprehend the directions of change in our environment. Is it any wonder our pursuits often seem an endless cycle of chasing new purpose and self-justification while lurching toward new ideas that sometimes seem ill suited to our core principles?

Lessons from a Fighter Pilot

In seeking new tools to help us move our performance forward more mindfully and to better understand and adapt to what is happening in the world outside our walls we should look closely at the lessons provided by John Boyd. Boyd was not a librarian or management guru. In fact, he began his career as a hotshot Air Force fighter pilot. Today, his influence, though sometimes obscured, runs deep because of his fierce and striking insights into seizing and winning the initiative—in warfare, in life, and in any competitive environment. These insights, presented through numerous briefings, contain much value for libraries. Understanding and applying them, and ensuring that our organizational staff are at least conscious of them, will help us expend our energies with more accuracy and agility. By absorbing his key lessons, we can learn to design and redesign our operations in ways that allow us to flourish.

Boyd’s insights most relevant to public libraries are rendered in his briefings “Patterns of Conflict,” “Destruction and Creation,” “The Strategic Game of ? and ?,” and “Organic Design for Command and Control.” Chet Richards, both a pupil and partner of Boyd’s, wrote a paper titled “Boyd’s OODA Loop (It’s Not What You Think),” which gives his interpretation of Boyd’s OODA Loop as well as the importance of implicit guidance and control and how it can be achieved in organizations.1As the title of his paper indicates, Richards attempts to correct some of the false and simplistic limning of Boyd’s complex and carefully rendered findings on the nature of conflict. This paper, in addition to the briefings, provides the basis for what is examined here.

Born in 1927 in Erie (PA), John Boyd was raised by his mother after his father, a travelling salesman, died when Boyd was six. He began his military career as an Air Force fighter pilot and flight instructor. Before he died in 1997, he became far more famous (and controversial) for contributions to military strategy and intelligent fighter aircraft development (his energy-maneuverability theory drove designs for the famous F-16 Fighting Falcon), as a singular bane to Pentagon careerists and proponents of bloated Air Force budgets, but foremost as a strategic thinker. It wasn’t in Boyd’s makeup to publish a formal paper or book because he saw his ideas as fluid and subject to constant revision. Instead, his ideas are codified primarily in the highly attended briefings (which could last up to six hours) he presented to high-ranking military and business personnel on conflict and competitive strategy. These briefings offer penetrating insights on how to overcome one’s adversaries, engage new information, deconstruct to create something new, and resist becoming a closed system disengaged from the ever-changing world. With an engineering degree from Georgia Tech acquired in his thirties while an Air Force major and tireless energy, focus, and rectitude, he acquired brilliant and contrary acolytes—some of whom were civilians—who worked with him, challenged him, and helped refine his conceptualizations. His intellectual foundation was deep and broad, and included Sun Tzu, Clausewitz, Godel, Heisenberg, and the second law of thermodynamics. Perhaps his most famous briefing, consisting of nearly two hundred slides, was “Patterns of Conflict,” which remains a stunningly powerful and inspiring synthesis of two thousand years of strategic thought. However, his unpublished briefing “Organic Design for Command and Control” will receive more focus here because it specifically illuminates the fundamental nature of the OODA Loop in our daily existence (work and life) and clarifies its importance to effective leadership and how we can strive to more effectively reinvent our organizations with accurate information.

The OODA Loop Explained

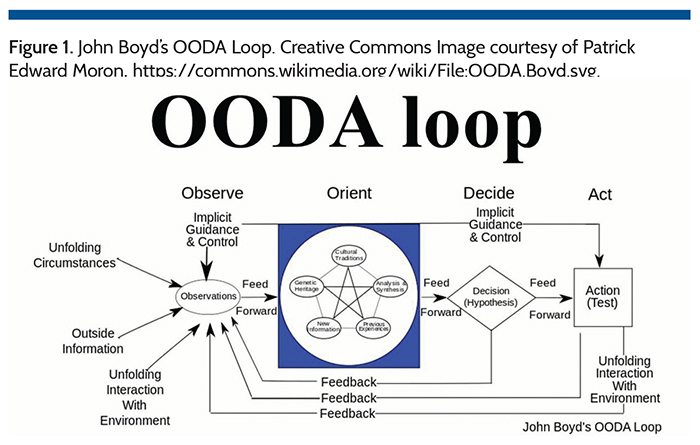

Boyd’s OODA loop has been misconstrued, misrepresented, and grossly simplified to suit the needs and perceptions of numerous interpreters. We may be familiar with the phrase of “getting inside someone’s OODA Loop”—disrupting their expectations and equilibrium in real time. Boyd’s OODA Loop contains this element but also much more. Essentially, the Loop has four nonsequential, endlessly cycling components: (1) observation, (2) orientation, (3) decision, and (4) action. These elements, and our ability to use them to enter the loops of other environments, are vital to our success as human beings and as organizations. Boyd flatly states that, lacking this ability, we will find it “impossible to comprehend, shape, adapt to and in turn be shaped by an unfolding evolving reality that is uncertain, ever-changing, and unpredictable.”2 The Loop that Boyd sketched is a complex visual flow chart demonstrating the process we undergo in life to become aware, understand, adapt, and thrive.

The last OODA Loop Boyd drew is more complex than many casual observers’ interpretations of it (see figure 1).

Note the Loop’s flow and the central importance of orientation. It encompasses all our acquired information, biases, and traditions and how we assemble them into an ever-evolving worldview. He expands on and addresses the importance of the orientation component in his briefing “Organic Design for Command and Control,” in which he suggests that the OODA Loop process is the essence of command and control and that orientation, “as the repository of our genetic heritage, cultural tradition, and previous experiences,” is the most important part of the OODA loop because it “shapes the way we observe, the way we decide, the way we act.”3

Reading the Loop

As we look at the Loop, we tend to “read” left to right and see a sequence unfold of observing, orienting based on what is observed, decision-making, and action. To dispel this simple formulation, we must look at the feedback loops built into the diagram and what is baked into each realm. We need to see how observations are processed by our biases to draw conclusions that we then act on—we then draw conclusions from the results of those actions and feed them back to our new observations. This is a constantly running engine in an ever-changing environment where observations are incomplete or we are overloaded with information, where previous experience colors future choice and the shaping of new mental models of reality, and where our actions must be relentlessly scrutinized to determine whether they demonstrate a coherent response or an inspiring formulation that can be effective in our operating environment.

In “Organic Design for Command and Control,” Boyd notes that our orientation (our ability to observe patterns) should encourage us to “expose individuals, with different skills and abilities, against a variety of situations—whereby each individual can observe and orient himself simultaneously to the others and to the variety of changing situations.”4 This describes the Implicit Guidance and Control (IGC) Loop on the diagram flowing from test back to observation so that, over time, new collective repertoire is acquired, allowing for better organizational responsiveness to changing situations.

Observing, to Boyd, is the act of looking out to the external world to acquire knowledge that we could apply in our own. What ties Boyd’s thinking to libraries is a fundamental argument he makes in various briefings; namely, that a successful and highly adaptive organization (a US military strike force or a public library) that willfully yet unconsciously engages in the OODA Loop handles fast transitions well. It is an organization that can operate rapidly and maintain that tempo. It is organizationally focused through a deeply ingrained shared orientation. This allows for employee assignment by aptitude and enthusiasm and unfetters them with full confidence in their ability to achieve established goals. It offers room to maneuver toward accomplishing goals in the manner they see fit.

How do we become comfortably aware of our observed environment? How do we train ourselves and staff to consistently and calmly craft new mental models using observed information? And how can we insure that our staff are compiling roughly the same models of new organizational realities in their minds? These questions are crucial because we know that libraries, like any organization, cannot afford the luxury of indulging conflicting perceptions of organizational realities. Unfortunately, some employees, including managers, become hopelessly closed systems, unable or unwilling to synthesize new information or, in the worst cases, even be aware of it. Thus, they base how they operate on old, comfortable models and ignore new reality and new information. Their differing, increasing disordered realities generate enormous friction and hinder innovation and rapid situation awareness and responsiveness. Their perceptions will ultimately produce unsympathetic thoughts toward the organization as it willfully acts on new outside information.

Organizational participants that base their understanding on hopelessly outdated—but endlessly comforting—mental models, eerily mirror the ignorance and dysfunction found in the inhabitants of Plato’s Cave in the famous allegory from the Republic.5Here we encounter the people chained to a wall in a cave, facing only their own shadowy reflections from a fire on the wall of the cave. This is how they build their reality, without any outside input that might prove useful in rendering more accurate detail to the world they observe. The individual who escapes, the philosopher—the one with a larger and more receptive organizational vision—is disbelieved when she comes back to them with a vision of the world (gained from observation and engagement) that doesn’t match their own. They prefer what they know and what they have fabricated from an organizational collection of truths assembled from an ongoing loop of reinforced invention, grievance, or lack of imagination. No organizational leader can afford to ignore these varying “realities,” however invented or self-accommodating. They represent real attitudes that govern actual behaviors. Only by understanding them can the leader determine where and with whom reorientation to the common vision is possible. Conversely, rather than forming incomplete and prejudiced views of these realities through willful ignorance or disposition, each employee (from director on down) must understand the operation’s true intent, and a shared, accurate (or as accurate as possible) depiction of its embedded realities must be realized for employees to act with implicit guidance and control throughout every level of the organization.

The Loop Yields Results

An organization continually running through the OODA Loop—one that regularly creates situations for disparate members to observe and orient simultaneously to a variety of changing situations—achieves a deeper ability to operate with implicit guidance and control. This ability, sometimes demonstrated through all organizational layers, can feel like an intuitive responsiveness and encourages creative problem solving in real time. It is embodied in fingerspitzengefühl, a deep, instinctive awareness that amounts to an almost tactile, fingertip feel of the organization’s energy, knowledge repository, and useable potential—an awareness that allows one to quickly grasp and intelligently adapt to an unfolding situation, often with other similarly attuned cohorts. At the highest level, one is not merely adapting but mastering the new challenges offered by the constantly shifting environment. This awareness allows us to encounter variety and rapid change (Boyd calls this “increasing friction”) while comfortably maintaining harmony and initiative. In this way we can increase the “performance envelope” of the organization.

Boyd’s “Energy-Maneuverability” and Libraries

In the 1960s Boyd co-authored a brilliant report on individual fighter aircraft performance that became a military standard. Called “Energy-Maneuverability,” it was initially classified.6He and Air Force mathematician Thomas P. Christie developed complementary energy diagrams factoring velocity, thrust, drag, and weight to measure operational maneuverability and efficiency for various combinations of engine, armament, and airframe. Given the specifics of each of these factors, they could generate a performance chart for individual aircraft at a specific altitude. This report is still used today to measure and to provide visual representation of potential fighter aircraft energy, which can then be translated into performance potential. What does this have to do with libraries? In theory, we could create our own sets of variables in tension and use them as our potential energy diagrams to calculate the “maneuverability” and efficiency of our organization in specific situations. We would be hard-pressed to practically replicate Boyd and Christie’s theory to compute our own organization’s useable or potential energy (or assets, if you prefer) because finding the correct measurable inputs might mean collecting data about our organization’s skills and performance that we don’t currently capture. For example, rather than tracking checkouts, reference interview counts, or holds filled, we might want to garner something quantifiable about our individual and collective technology skills, customer service responsiveness, and rapid orienting skills. We could then calculate what an overall perfect score would look like. Further, we might then measure and grade our scores for ongoing patron transactions and interactions as well as the pace of developing and implementing of new initiatives. The underlying assumption of this example is of a strong correlation between our IGC rating and organizational performance. The IGC value of an organization would reflect its actual ability to harness useable potential for taking initiative and affecting change. Since we currently lack such an evaluative tool, it remains important to improve our organization’s performance envelope across a range of spectra. “Drag” and “weight” can be defined by the identifiable elements of friction restricting the responsiveness of our organization. These elements can include leader mistrust, silent agreement, hidden motives, poor synthesizing of information, inadequate training or background to meet challenges and opportunities (or to even recognize them), and more.

Doctrine, not Dogma

A warning is long overdue about the concepts being shared here. Boyd professed sharp concerns that today’s doctrine can easily become tomorrow’s dogma. He did not want to see an organization’s guiding principles codified in any way. Ideally, in his mind, IGC and fingerspitzengefühl were part of an unwritten language evolved through the development of shared mental models. But, as we have noted, IGC and fingerspitzengefühl go well beyond the shared understanding of a task. Boyd considered the ability to determine and nurture the accuracy and depth of common understanding in an organization to be one of the primary functions of leadership. He envisioned common understanding as a collective orientation (the big O in OODA) that transcended the common frictions of our personal realities. The mental models to which he referred command us to develop a new repertoire and to use open-loop learning to escape our reflexive assumptions and preloaded responses to challenges and opportunities. But how do we get an organization to build shared mental models effectively so its members are reading from the same script? How do we know that providing opportunities for all to gather, observe, and orient to varieties of changing situations will build harmony, shared focus, trust, etc.? How do we know the same lessons will be learned and values blended?

Practically speaking, in all types of settings and with any number of employees, an organization’s guiding principles should be firmly and clearly articulated and understood by all. Further, they should be demonstrated and woven into the weekly and daily fabric of the organization’s operating philosophy and action. However, it is crucial that no one ever feel chained to specific language or even procedures but only to desired outcomes. This, to Boyd, is imperative. For example, Director Smith, having gathered input over time from a variety of organizational players, considers several new initiatives that have bubbled up or been synthesized from other concepts, and decides that the organization will implement initiatives two and six; the “how” of how it happens is of no interest to her (budget excepted). A sufficient supply of organizational implicit guidance and control can begin the process of assembling her desired outcome without a blueprint. This is so because the principle players understand in great detail, with some tactile awareness, how her vision of the desired outcome unfolds. They then assemble the components to make it operational. In the conception process of an idea, formality follows uncertainty. Informality and brainstorming rule in environments driven by implicit guidance and control.

Shaping our Environment

In Boyd’s briefing “Organic Design for Command and Control” he emphasized that shaping the environment requires four qualities: (1) variety, (2) rapidity, (3) harmony, and (4) initiative. To adapt to and shape unfolding circumstances around us we need to demonstrate all these qualities plus insight, adaptability, and agility. In fact, agility is often manifested in the tempo of our adaptability to new information and insights. We process, react, and respond, often simultaneously.

IGC is the ultimate outcome of a highly adaptive organization that has embraced an awareness and engagement with OODA Loops in many environments. It mirrors the speed and flow of the organization. In “The Real OODA Loop,” Richards spends much time on IGC. IGC can only be achieved through development of a deeply shared orientation. Boyd explained: “The key idea is to emphasize implicit over explicit in order to gain a favorable mismatch in friction and time (i.e., ours lower than any adversary’s) for superiority in shaping and adapting to circumstances.”7 Written orders (or instructions, guidelines, etc.) simply took too much time to act on. Boyd’s formulations also make clear that “adversary” or “opponent” could easily refer to any competitive environment in which an organization finds itself. Thus, “warfare” translates to marketplace and to public libraries and their ongoing relevance to their communities.

Boyd’s Command and Control

In “Organic Design for Command and Control,” Boyd identifies friction as the atmosphere of war. It is “generated and magnified by menace, ambiguity, deception, rapidity, uncertainty, mistrust, etc.”8This atmosphere exists in all competitive environments and all organizations with more than one employee and goals which the org hopes to achieve. All these factors can be amplified, but they are all recognizable to anyone familiar with typical organizational behavior. Boyd then explains that friction is diminished by implicit understanding, trust, cooperation, simplicity, focus, etc., but variety and rapidity (qualities we need to embrace) tend to magnify friction. Thus, we need a profound collective shared orientation to pull the throttle of IGC.

Manifestations of the Loop in Library Practice

Before identifying methods for building collective shared orientation in our libraries it might be instructive to examine how fully engaged libraries act when operationally aware, if only on an instinctive level, of OODA Loop and Implicit Guidance and Control environments. Such libraries can make agile and dynamic leaps forward to appeal to and attract their user bases. They consistently get inside their follower’s OODA Loops as they ceaselessly orient and reorient to their environments. As they cycle through Loops and continually readapt to their environments, they adapt their patrons to the new tempo they create. They do so by identifying unexpected new opportunities for patron interaction and unleashing their high creatives (employees) to develop the services and customer experience in ways that deviate from traditional organizational procedure and method. Thus, friction gives rise to flow and innovation.

What does this arrangement of the minds look like to the patron? What are these libraries doing to generate surprise, awe, and loyalty?

The Library of Things movement has been receiving a lot of attention recently, but one could argue that the first “library of things” wasn’t even a library at all. In 1979 the Tool Library was established in Berkeley (CA). This forerunner of libraries of things was followed by the Toronto Tool Library in 2012 and evolved into The Sharing Depot.

Comic book convention (comic con) events began appearing in libraries once libraries began to see themselves as logical venues for such bold and nontraditional programming initiatives. San Diego Central Public Library was a pioneer, followed by others, such as Boise Public Library.

These were far more than new collections or programming initiatives; they were manifestations of the new ways organizations visualize themselves from outside in to create fast-cycling unexpected programming partnerships, dramatic changes to service points, and the flattening of the organization in a way that released talent to engage the audience more directly. They demonstrated harmony of effort, shared mental modeling, test and observation, and responsiveness and effective orientation to emerging external realities.

If we examined specific examples of the Library of Things initiative or library comic con events, we would see the many initial barriers to implementation and execution. Funding and adequate space are issues, but employee resistance to such initiatives often presents the biggest friction issue, at least until the majority of resistors are converted or depart. Ideally, everyone should champion such bold initiatives, but at minimum, the high-energy stakeholders are usually able (with some difficulty) to get a new initiative moving, especially if it is an event or a specialized library feature rather than an ongoing new service. These committed stakeholders will push back on or ignore the friction caused by backward-thinking employees and leaders who take comfort in the way things have been done before and are too comfortable embracing their own past impressions of library success. Pushing dramatic new library initiatives is analogous to Boyd’s description of exploiting breakthroughs. At these times a rapid tempo is needed. This cannot be realistically expected of the entire organization, but prime organizational movers will drive the tempo and the changes embedded in the new initiative if leadership has provided the freedom of movement to fulfill clearly understood organization outcomes.

Rather than effective IGC, organizations often possess composite and flawed realities based on the relationships of understanding woven by insular perspectives of its employees. These hidden relationships, which provide meaning and significance, are often at the root of organizational conflict and rot. Managers frequently treat emerging situations according to their face value because they cannot see the activity hidden beneath expressions of dissent or false assent.

Boyd teaches us that to maximize performance, an organization’s leaders must honestly observe operational realities, budget challenges, and demographic factors to structure their orientation accordingly. High-potential people, at any level, must be identified and nurtured congruent with organizational ideals so

that (according to Richards’s interpretation of Boyd’s Loop framework) actions will usually flow without explicit cues or commands. This systemic “situation awareness” has profound implications for our ability to influence our evolving environment. It is a core element of IGC.

Boyd’s Patterns of Conflict

Boyd was referring to battle when he wrote, “Establish focus of main effort together with other effort and pursue directions that permit many happenings, offer many branches, and threaten alternative objectives.”9 This is a summation of a thriving, energized organization with motivated employees mustering enough experience to demonstrate instinctive and effortlessly repeated performance in an array of activities.

For Boyd, the ultimate strategic aim is to improve our capacity to adapt as an organic whole (to our environment) (so that we can effectively cope with events as they unfold) and exert our influence on those events in a timely fashion.

Making Things Operational: An Examination of the Loop Sketch and Boyd’s “Destruction and Creation”

In 1976 Boyd wrote “Destruction and Creation,” a representation of the OODA Loop in action.10 The interrelationships of the four Loop elements is striking, but the crucial elements are observing and orientation to the constant parade of information. Identifying what is relevant is vital, either because it is useful for constructing new organizational realities or because it appears as a threat to our thriving as an entity. Accurate and timely identification as a group is even more powerful and will allow IGC to flow. How can we take Boyd’s vision and make it operate as a training exercise?

Exercise 1

Have staff break into subgroups of four or five per table or room. Choose an article from a (preferably local) newspaper and ask them to examine a story that talks about some aspect of social change or trend. Than take another story that contradicts that change or trend and then another to support it and ask them to analyze these through shared discussion (this could be in multiple short sessions to allow for reflection and a gradual awareness of how each of them processes the same information). Then ask them to collectively look at Boyd’s Loop sketch and process what they’ve learned. Ask them to contribute something about how their own experience, genetic heritage, and traditions might have contributed to how they interpret their environment. You can take the information from the source material and ask separate groups which of the concepts presented line up with their group’s version of observed reality. You might then compare each group’s findings and tease out why they may differ and, more importantly, what inherent conditions or traits might have shaped the orientation of participants.

Exercise 2

Have staff break into subgroups of two or three. Provide them several statements that reflect various examples of current conventional societal wisdom and ask them to examine these and demonstrate how they can be reformulated. This helps examine the pernicious effect of conventional wisdom in the current zeitgeist. Conventional wisdom, unexamined, seems rational and easily supportable. It also is a roadblock to accepting new information and is commonly encountered in closed-loop organizational thinking.

Exercise 3—Building Boyd’s Snowmobile

This is the culminating exercise in attempting to draw new impressions and utility from random assorted components and is drawn from Boyd’s briefing “The Strategic Game of ? and ?.”11 It forces participants to examine well-worn and familiar constructs of their own, and their group’s thinking. Rather than generating solutions from root sources and constructs with which we are most comfortable, we shatter those constructs and disparate components. In Boyd’s classic example, he drew from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and the second law of thermodynamics to conclude that “one cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself.”12 In the exercise, Boyd used four images or constructs, which he referred to as domains. Each domain could be understood by looking at its constituent parts and their relationships. He presented these domains or environments as coherent and familiar. He then showed them as merely scattered components intermixed with the parts of the other three domains, thus creating a “sea of anarchy.” He then asked his audience to examine this anarchy and imagine constructing something entirely new from some of the random components by seeking out common qualities and hidden connections to yield new realities. In his exercise, the outcome of reassembling the disparate parts from four distinct activities resulted in a snowmobile. It is a difficult exercise in analysis and synthesis as it forces participants to dispose of all preconceptions, set aside the familiar, and gain understanding by interacting in new ways with our environment. This allows us to grow our repertoire. The exercise doesn’t stop there—to operationalize any new assemblage, it must be tested, monitored, and verified to ensure it is harmonious with the reality we operate within. We must ask if we can afford it, if we have the expertise to exploit it, and so on.

At the end of these three exercises participants should be brought together to process the recorded findings of each subgroup, particularly how they confronted their own cultural and genetic blinders, or even blinders they have superimposed on themselves for the sake of convenience, conformity, or identity. This is hard work, but over time we can reduce our reflexive responses to observed inputs and orient more effectively to new information. This way, we can overcome and even embrace challenges and ultimately find new and effective ways of interpreting what passes for reality and fashion novel responses that excite our patrons. And of course, build snowmobiles.

These group activities can be modified and repeated regularly until our awareness of the Loop (which embodies much of Boyd’s conceptual thinking) as a mental circulatory system is recognized to the point that we no longer must name or acknowledge its impact. Expected results would include an embracing and repurposing of new information and seeing operations from outside in, thus allowing the creation of new and nimble responses to the ever-changing environment.

Summary

Good leadership requires a clear perception of unfolding events and an ability to appreciate and place accurate worth or value on them as well as on the underpinning of ideas beneath the events. This is the crux of Boyd’s investigations in “Organic Design for Command and Control.” This “appreciation,” as Boyd called it, builds risk confidence rather than risk aversion because one can recognize the quality of the components of an idea from outside in and accept that some results may vary. Risk confidence evolves naturally as an organization masters some level of IGC, shared orientation, and the OODA Loops we live in. Boyd’s insights offer tremendous opportunities for libraries willing to explore and embrace them. With imagination, many useful tools may be rendered from his rigorous and precise investigations. We can get started anytime.

References

- Chet Richards, “Boyd’s OODA Loop (It’s Not What You Think)” (Mar. 21, 2012), accessed Apr. 12, 2018.

- John R. Boyd, “The Essence of Winning and Losing” (briefing, Sept. 2012), accessed Apr. 12, 2018.

- John R. Boyd, “Organic Design for Command and Control” (unpublished briefing, May 1987), slides 26, 16, Defense and the National Interest, Dec. 6, 2007.

- Ibid., slide 18.

- Plato, Republic, VII, 514.

- John R. Boyd, Thomas P. Christie, and James E. Gibson, “Energy-Maneuverability,” declassified report, Air Proving Ground Center, Eglin AFB, Florida, Mar. 1966, accessed Apr. 12, 2018.

- Ibid., slide 22.

- Boyd, “Organic Design for Command and Control,” slide 8.

- John R. Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict” (unpublished briefing, Dec. 1986), slide 132, Defense and the National Interest, Dec. 6, 2007.

- John R. Boyd, “Destruction and Creation” (unpublished paper, Sept. 3, 1976), Defense and the National Interest, Dec. 6, 2007.

- John R. Boyd, “The strategic Game of ? and ?” (unpublished briefing, June 1987), Defense and the National Interest, Dec. 6, 2007, www.dnipogo.

Tags: John Boyd, library technology