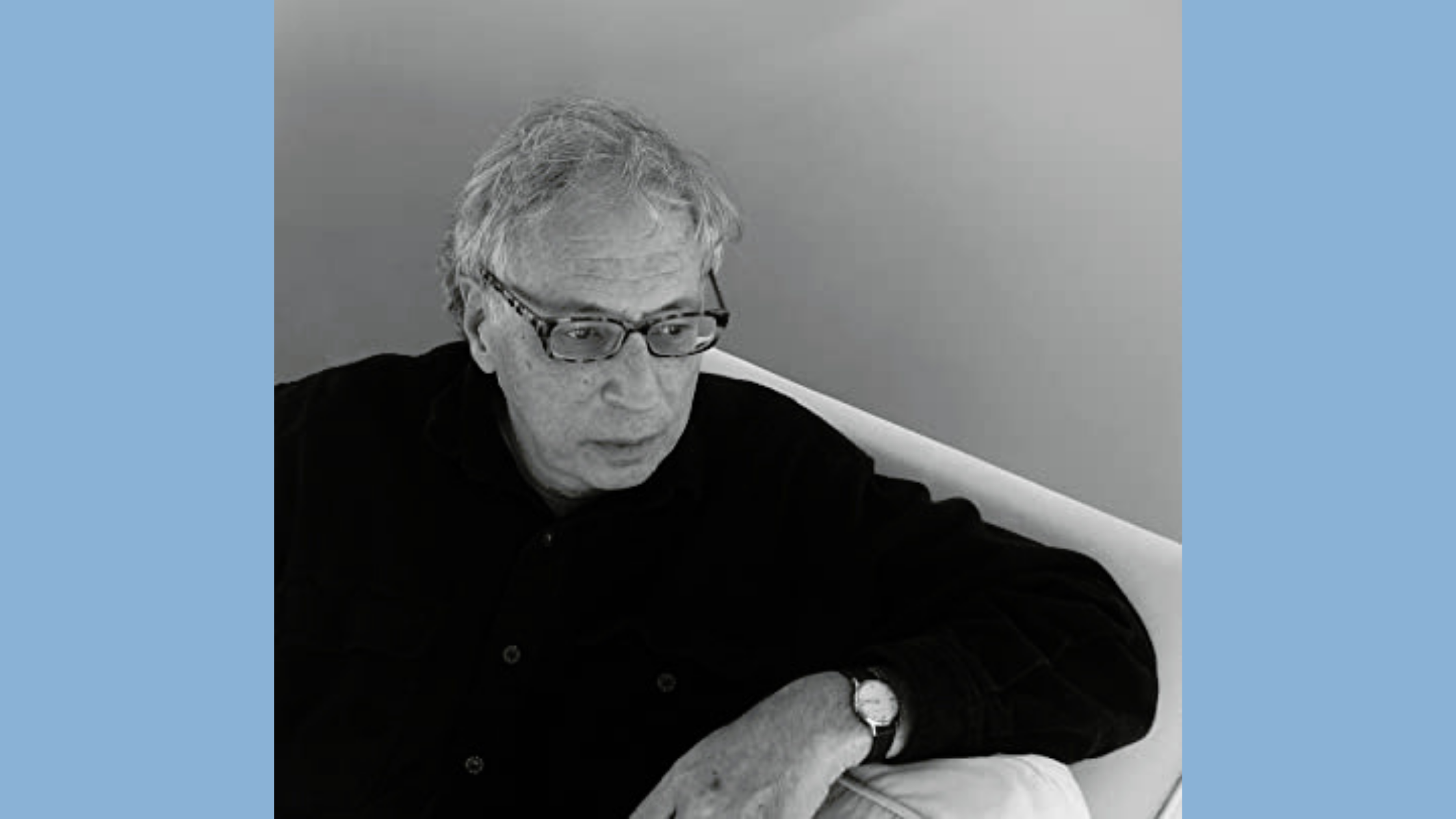

“My Process is Usually One of Necessity and Escaping Disaster” — Jeffrey Lewis On His Haunting New Novel

In Jeffrey Lewis’ emotionally resonant Land of Cockaigne, an older couple find themselves unexpectedly battling their community when an outreach program based on their late son’s dream sparks an unexpected controversy in their small town. Walter and Charley Rath have taken their windfall from savvy financial investments to support a life in Sneeds Harbor, an idyllic community in coastal Maine. There they buy not only a beautiful home, but also a neglected 220-acre camp that Charley uses as studio space. Although outsiders, they have spent over two decades there, raising their son Stephen and forging deep connections with their neighbors. As they head towards late middle age, their lives are upended when Stephen dies in a random act of violence. Struggling to carve meaning out of his death, they decide to put in motion one of his last goals, to create a program where teenagers from the Bronx would be able to spend two weeks in Maine. Walter and Charley’s opening up their home, and thus Sneeds Harbor, to young people predictably provokes huge reactions from their fellow community members, resulting in a shocking act the last night of the young men’s visit. Lewis plunges the reader into the rich interior lives of his characters, including not only Walter and Charley but also Stephen’s grieving girlfriend Sharon, various townspeople who oppose their action, and the visiting young men themselves. The result is an extraordinarily compassionate look at race, class, and community. Lewis, who began his career as a television writer, winning two Emmy Awards for “Hill Street Blues,” is also the author of Bealport: A Novel of A Town, and Meritocracy: A Love Story, The Conference of the Birds, Theme Song for an Old Show and Adam the King, four novels which comprise “The Meritocracy Quartet.”

The book dives into the minds of different characters: Walter and Charley, their son’s girlfriend Sharon, plus all of the people in town. Was there a particular character who was the entry point for you for the novel?

If I could point to anyone, I suppose, Walter Rath, the husband of the couple who gets the story in motion. I think the husband is, in part, I can’t say based on any real person. The characters are almost more based on fictional characters than real people, although I’m sure there’s stuff of me in Walter Rath. Did you ever read Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities? It’s a wonderful novel, maybe the greatest of the twentieth century novels, right up there with Proust and Joyce in the pantheon. Musil was an Austrian writer who wrote about the Austro-Hungarian empire in the days before it collapsed in the First World War. He had a couple in that book named Walter and Clarisse, and although they weren’t like Walter and Charly in my book, nonetheless I felt an urge to honor them somehow in the name. Walter’s last name Rath is, in a way, an homage to another character in the Musil book, Arnheim, a German industrialist. When Musil published the book, Arnheim was widely believed to be based on Walter Rathenau, who had been the German Foreign Minister after the First World War, who was Jewish and was assassinated in 1922 by right wing groups. Anyhow, my great admiration for the Musil novel resulted in at least in the name of Walter Rath, and some combination of that and some character I used to see on an old PBS show—a kind of almost reactionary PBS show—called Wall Street Week. They used to have a character on who would be commenting on the burgeoning technology companies of Silicon Valley. A little bit of that idea, a little bit of a Silicon Valley type who briefly lived in the town in Maine where I spend a good chunk of every year, and then of course a chunk or two of myself. I suppose that chunk or two of myself, and the ability for me to pop off the way that Rath occasionally pops off, both helped form the character and made him, in final answer to your question, probably the character I most identified with and find to be the easiest entry point into the book.

I loved Walter. He’s so philosophical and idealistic. I especially loved the description of Walter as a “poor man’s Prospero.”

I suppose I’ve got a little bit of that in me as well. I would love to have an island where I could try and make things work out the way I’d like them to work out. (laughs) Lots of luck, right?

How did you arrive at the polyphonic nature of the novel, with everyone narrating different chapters of the story?

How I arrived there, I have no idea. I wish I could be more introspective about my process. My process is usually one of necessity and escaping disaster. That is to say, “I can’t do this at all, right? There’s no way I can write this book. Oh hold it, maybe there’s one conceivable way. If I follow this way long enough, maybe conceivably I could at least begin to write this book.” It’s typically those sorts of decisions, those sorts of morning confrontations, that lead towards the book. I didn’t decide, “Oh, wouldn’t it be lovely to have a polyphonic book,” but I would say that this book, along with some others I’ve written, either suffers from or benefits by something that I wrote in another book once, in Theme Song for an Old Show. The narrator says something like, “The novel as sociology? A dirty job, but somebody’s got to do it!” That’s a little bit how I feel about my books. In some ways, they’re not the most intimate or subtle maybe, in terms of interpersonal stuff. I hope they are, I’m not out there banging the drum saying they are. But one thing I meant to undertake when I seriously started writing fiction, which was a little more than twenty years ago, was that I didn’t feel that the story of our country was being told as accurately, or at least those portions of it that I knew. Of course, other portions I accepted what people said about it. I felt the things that I knew about hadn’t been adequately portrayed, and certainly not in movies and television, where commercial motives tend to curdle and alter and corrupt the structures of character and plot. Too much action at the expense of too little feeling, for instance. In any event, I set out in my first books, which were loosely grouped under the title “The Meritocracy Quartet,” to tell the story of my generation as I understood it. It had a kind of sociological ambition, which was to describe society as I understood it and the development of American society over a forty-year period. Subsequently most of my books have done the same, there was one that notably didn’t, but most of them have. Plainly, in this one, Land of Cockaigne, there are just a number of stakeholders, so to speak, without whom the book wouldn’t be a book, and a certain kind of story of American society couldn’t be told.

The book takes place at such a specific moment, recently after Trump’s election, and Governor LaPage’s remarks about race and the opioid crisis play a significant role in the book. The characters are dealing with changes in their lives and also combatting news they encounter on the internet. What was it like exploring life in a small town in Maine at that specific point in time?

Like many people who live in Maine—not all of them of course, but a good chunk—like many people who love Maine even though we don’t live here all the time, I was appalled by the comments of former Governor LaPage in 2016 that were basically racist in nature and in expression. I think I wanted to do something about that. I wanted to make some sort of answer to that. It was certainly one of the motives that got me going in the book. There were others as well, but at this moment in time, when the future of this state of Maine is again up for grabs in so far as ex-Governor LaPage is planning to run again next year, I feel a certain urgency about the book. I feel like I’m glad to have written it, although I wrote it without knowledge of his plans, and feel it’s timely to be coming out now.

One of the amazing things about this book is its economy. You’re able to cover so much emotional territory in under two hundred pages, but it’s also easy to imagine there being another version of this book that’s five hundred pages. For you, what’s the appeal in writing such a compact novel?

I don’t know what the appeal is. Basically, that it’s shorter. You don’t have to write as much. (laughs) Really that’s the great appeal. That’s just a side benefit, but that doesn’t determine what I’ve done. I write as much as I can write. Thinking back on it, there’s a lot of things that aren’t in this book that might have been in that book of five hundred pages. I would go back and say there are a lot of things in some traditional novels that I’m not that interested in. For instance, I’m only interested in descriptions of characters when they’re really interesting. I don’t need to know every detail, every mole on a character’s face, unless there’s’ something peculiarly interesting about that mole. In most of my books, I’m guessing that there’s much less description of characters and even of places than in other people’s books. At the same time, I do try to follow my own imagination in putting in those details that I think are telling. I don’t do it for economy’s sake, I do it because that’s what I can remember, or that’s what I can imagine. If I met you in person and somebody asked me to describe you later, I’d probably come up with one or two details that struck me as interesting or stuck in my imagination and memory. Whereas I can imagine other writers could go through you like an anatomy lesson. I just can’t. My imagination doesn’t work that way and I’m not that interested. I’m interested in the things that seem to me telling, seem to stick. In a sense, when I write, I step back a step from my own memory and imagination. Rather than try and invent everything, I try simply to record what my memory and imagination have already discovered, what has impressed them rather than trying to sort of go out and create a whole world.

You wrote for years on television, most notably on “Hill Street Blues.” I feel that this is a question you must get asked a lot, but how have your years writing for television informed your approach to novels?

You’re right, It’s a question that people have asked me a lot, and I don’t remember one single answer I’ve ever given. I’ve probably given a different answer every single time, in part, because I don’t really know. I don’t really have a good answer, I have partial answers. One partial answer is writing in opposition to what I wrote on TV, which is to say writing certainly for commercial television when I did work on it, was very much eyeball driven and to keep people from grabbing the channel changer and changing the channel. In other words, holding people’s attention constantly, with something new or something amusing, or something that got you to the next commercial, so to speak. I felt that even then, even with the wonderful things we managed to do on “Hill Street,” and they were wonderful and I loved working on that show. I loved the camaraderie, I loved the friends I made, I loved a lot of the stuff we did, but I felt in part it didn’t fulfill why I set out to be a writer. After college I went to law school. I could have been a lawyer, I suppose. I didn’t want to be a lawyer, partly because I didn’t want the day job. I thought there had to be a better way to live life than working nine to nine every day. In addition, I had this urge to write. The urge to write was probably from hurt feelings in my childhood, but was also to tell the truth about certain things that I felt the truth wasn’t being told about, or that I had perhaps to tell about, or perhaps that I could garner attention myself if I could write about them. In any event they were the kinds of things that were not eyeball-grabbing. They weren’t the kinds of things that you could easily sell on television because they might not keep people watching to the next commercial. In the end, I felt that I still wanted to write those things, and it was quite a transition to move away from, like I say, the commercially driven premise of American television at the time and what is still American television mostly, to something more personal. I felt I’d be dishonoring myself if I didn’t at least try. Given that I got lucky—honestly a lot of luck involved—to have landed on a show like “Hill Street” where I could parley that some years after to enough of a kind of treasure chest that I could afford to indulge or tempt my initial instinct to write. So I did it, I took my earnings and like Walter Rath leaving Silicon Valley in Land of Cockaigne, I took my winnings and started to write what I wanted to write. I felt that it needed to be written because if I didn’t tell the story, nobody was going to and a chunk of our shared lives would vanish forever. There’d be no record.

That’s maybe a longwinded and high-minded answer but it’s as close as I can come to the truth. Another way of looking at it would be what I got out of writing for TV? I think that includes a certain fluency and confidence and maybe even a desire not to overwrite. You mentioned the shortness of my books, well a TV script is only fifty pages for fifty minutes. A movie is only a hundred or a hundred twenty pages for a hundred minutes. You learn to leave out stuff. Of course in TV and movies, you can leave out a bunch of stuff because you’ve got wonderful actors and directors and set designers and location managers and everybody to fill in all the cracks. In fiction, I suppose you have to fill in more cracks. You have to know more about what you’re doing.

Tags: Jeffrey Lewis