“That Little Brown Ball Saved My Life” — Ray Scott On His Compelling New Memoir and Groundbreaking Career in the NBA

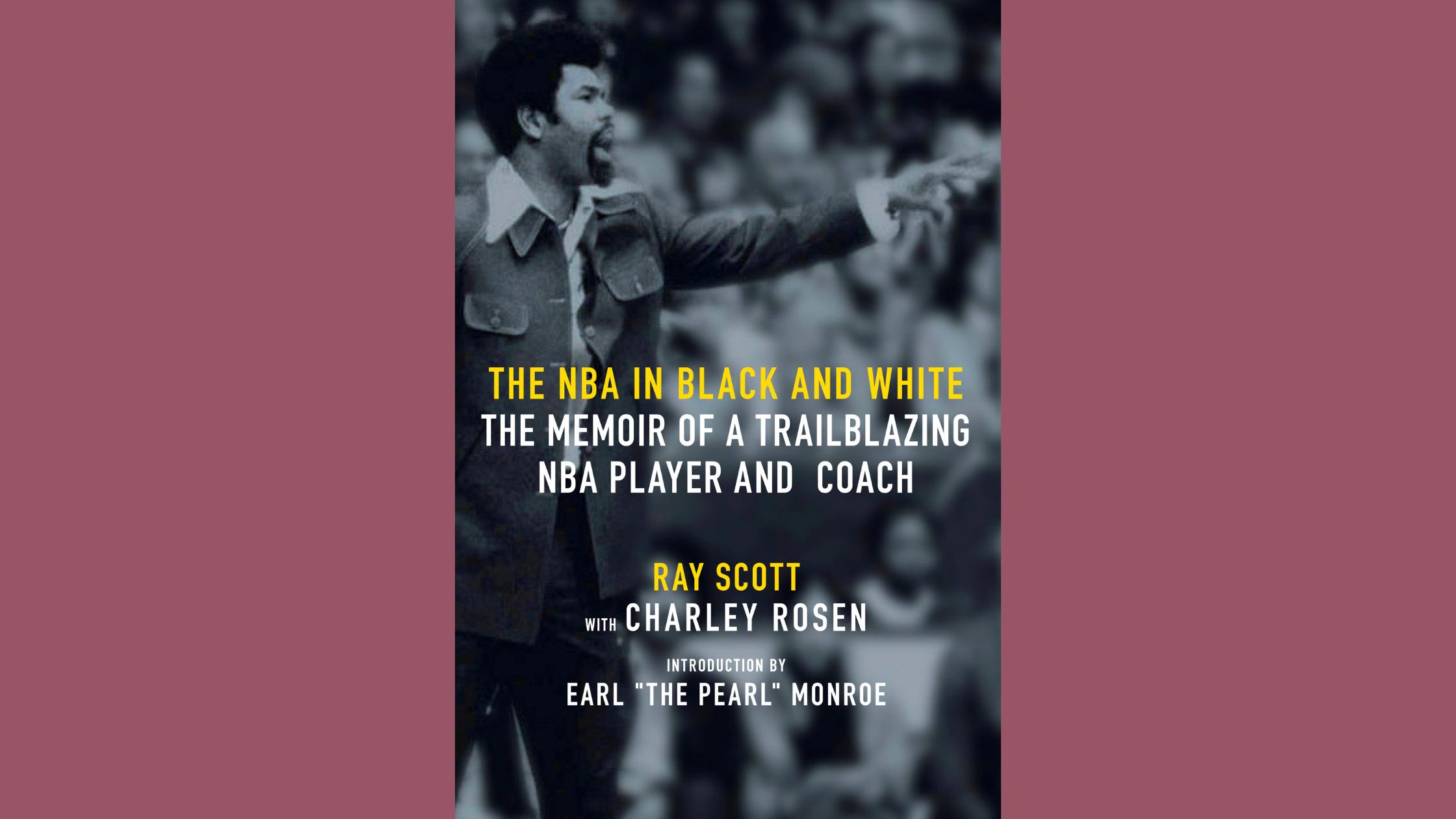

Ray Scott played a formative role in the creation of the modern day NBA, not only through his years playing for and coaching the Detroit Pistons, but also for his contributions to establishing the NBA players’ union in the 1960s. Now, in his richly told memoir, The NBA in Black and White: The Memoir of a Trailblazing NBA Player and Coach, Scott gives readers and basketball fans an unprecedented look at those early years, from growing up playing against Wilt Chamberlain on the basketball courts of Philadelphia, to unexpectedly being named head coach of the Detroit Pistons in the 70s. Scott also details his role in the civil rights movement, from meeting Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X to working alongside Coretta Scott King. Scott guides readers through the intimate moments of his professional life with warmth and humor, recounting the past with integrity and compassion. Critics have praised Scott’s book, with Publishers Weekly proclaiming it “a valuable addition to hoops history.” Scott recently spoke with us about his early days on the court against Chamberlain, his unexpected path to coaching, and growing up in the library.

Your book begins with such a lovely depiction of your mother and stepfather, Can you talk about them? What were they like?

It was like a storied childhood, but you know, not one of the great “haves.” We were “have-nots.” We lived in Philadelphia, so growing up as a kid, being aware of my environment, it was like, “Okay, I’m here as a stepchild at the age of four-years-old.” This man comes into my life—this man my mom knew, she was a young mom, she was in her twenties. This guy comes into my life, and all of a sudden, my life becomes ideal, in that I become this everyday kid walking to school, coming home and having lunch, having a little brother that’s born. We go along for about four or five years, and my dad dies. I did not know at the time that he had adopted me, so when I found that out, that was just unbelievable. Instead of John Raymond Howard, I was John Raymond Scott. For a little kid, you get to eight, ninth, tenth grade, we all want to belong. Even though my father had passed, I could make a reference to my father, Sylvester Scott, and my mother, Vivian Scott, so that was good. And then I had my little brother, Marvin Bernard Scott. There we were, without my father, and we quickly became latchkey kids. I went from the expectations of a kid growing up and playing outdoors to now being responsible for my baby brother, because my mother had to go to work. When my mother became employed, the care of my little brother was under my aunt and me. It just changed the game. I just remember things in my life that made me happy, and one of the things I felt that saved me and brought me forward as a person—because I was very tall—was playing basketball. So basketball became my refuge, but it also became my life. That little brown ball saved my life.

You grew up playing basketball in Philadelphia, where you frequently crossed paths with such players as Elgin Baylor and Wilt Chamberlain. What was it like playing basketball with these legends at such an early age?

I was taught humility early on by playing against those guys. (laughs) You grow to be six-foot-eight in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and you’re just a guy, because across the street at the other school, at Overbrook High School, is Wilton Norman Chamberlain. I met him when I was fourteen and he was sixteen. He was two years older than me, but he was a year ahead of me in school. I was always looked upon as the guy that was supposed to compete against Wilt, and there was no such thing. There was no such creature on the planet. I think William Felton Russell—Bill Russell—got as far with that as he could. Kareem got a little bit of it, because Wilt was still playing at the end of his career and the beginning of Kareem’s career. But for me in high school, at six-eight and Wilt was like a seven footer—when you say that, people look at it in terms of height. No, I mean he was a seven footer in height and talent. (laughs) To see that development in him and be part of that was great.

Philadelphia was a great emporium of basketball. We were turning out All-Americans, Guy Rodgers, Hal Lear, Wayne Hightower, Walt Hazzard, Wali Jones. We were turning out outstanding players but we all came under the shadow of Wilt. There was never going to be a basketball player born in Philadelphia that was better than Wilt, and so far there’s not been. I keep looking. I’m in my eighties and I don’t see it. (laughs) It just doesn’t happen. We thought we got close one year with Rasheed Wallace at Grant’s High School. We said, “Oh this could be the second coming of Wilt.” And Rasheed was a great player, but he was not the second coming of Wilt. There just has not been someone born that has taken that role.

Then you talk about Elgin Baylor. I saw Elgin Baylor as a twelve-year-old when I visited Washington D.C. I’m watching this guy that is playing basketball in a way, for a twelve year old, that I’d never seen anyone play before. I stoked that away and went back to school. I went to high school and graduated, and picked my college, the University of Portland in Oregon. I go out to Oregon, and there number one rival is the University of Seattle. And who’s the great player at the University of Seattle, but Elgin Baylor? Now I’ve seen this guy never miss a shot, never lose a game! (laughs) So that’s where I make my debut. That’s why I say, “God gives you humility, whether you think it’s there or not. He will give you humility.” I went up against two of the greatest players in the history of basketball. The other two names I would add to that would be Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell. Those were the four guys the current NBA is built upon. They were just outstanding people, but also incredibly talented players.

Your book shines a light on work that Oscar Robertson did in unionizing the NBA and improving working conditions for NBA players. Can you talk about Oscar? What was he like?

One of the proudest periods of my life was in the middle sixties when Oscar formally hired an attorney and formed the NBA Players Association. Your life is built on snapshots, all of our lives are. I remember the snapshot of sitting in the room. I was on Oscar’s Labor Relations Board, the union. I’m sitting in the room. I think I was with Oscar, Walt Bellamy, Archie Clark, Don Nelson. All players, but Oscar is our leader. He’s brought in the attorney, he’s had the meetings where we galvanized ourselves and then said, “Can we get a meeting with the owners?” The owners agreed, in 1966, to meet with us. This is huge. We go into this room, and there are these owners, the great promoters of the NBA, which was Eddie Gottlieb, Ben Kerner, Arnie Hoeft from the Baltimore Bullets. The millionaire in the room at that time was Jack Kent Cooke, who owned the Washington Redskins and the Los Angeles Lakers. We’re sitting in the room with these gentleman, and they ask Oscar to make a presentation. Oscar makes his presentation, and Sam Schulman, the owner of the Seattle team, said, “That was a great presentation. We have to get this done.” I remember Jack Kent Cooke saying to Eddie Gottlieb, “This was a fine presentation by these young men.”

My buttons were popping, but it was all Oscar Robertson. This was 1966. By 1970, we had certified ourselves as a players’ union, and that’s when we elected the new officers with the larger certified union in Puerto Rico. Oscar led that with our attorney Larry Fleisher. Oscar put his career on the line to go against the owners and say, “This is what our players deserve.” He filed the suit. Just as he was filing the suit, I was leaving the NBA and going to the ABA, but I followed it very closely. I got involved again with the players’ association when I came back in 1972 as a coach with the Detroit Pistons. Oscar was still leading the charge. He was a phenomenal, phenomenal man. Personally, I think he sacrificed his career. The owners are never going to see you as on their side, so all the jobs—the coaching jobs, general manager jobs—all that stuff passed Oscar.

I just talked to him a month ago. We were talking about how the NBA is progressing. I said, “The regret that I have is that you never got to achieve those great levels that the NBA achieved, and yet you’re the guy who put his neck on the line and got us there.” Think about that. He may have been one of the greatest basketball players ever, and yet he put his neck on the line. He was not so concerned with his game and his success, he was more concerned with the players and what they achieved in basketball.

He comes across as such an amazing person in the book.

Just as an aside, I’ll tell you again how amazing he is. A lot of people don’t know, Oscar Robertson’s daughter suffered from kidney disease. She needed a kidney. She walks around today living with her father’s kidney in her. That’s the depth of the man. I have so much admiration for him.

Going back a little bit, you were hired as a teenager by Haskell Cohen to work and play basketball at the famous Catskills resort, Kutsher’s. What was your time like there?

You just got the biggest smile on my face. That was such a great part of my life, because I had known Haskell since I was sixteen. Haskell Cohen worked for Parade magazine and he worked for the NBA. He brought me in as a sixteen-year-old—again, a six-foot-eight kid. He would come to Philadelphia and take me to the games. He had me in the NBA office in New York on the eighty-fourth floor. He was someone I was really connected to. He said to me when I was eighteen, “I want you to be a bellhop in Kutsher’s, because for the last two summers we had Wilt Chamberlain.” We went up to Monticello, New York. It was one of the greatest things ever to be around other All-Americans. I was with Al Butler, York Larese, Lee Shaffer, all these great players.

There was a basketball league. That’s where they started the big All Star game for the NBA. In 1958, the year after I was there, Maurice Stokes collapsed with encephalitis. Jack Twyman, who was twenty-three years at the time, was in Cincinnati. He happened to be a team mate, and he just started taking care of Maurice. Somehow he and Haskell got together. They colluded, it became the Maurice Stokes All Star game, and we raised money for Maurice Stokes at that game. All of the guys would come in from the Lakers, from Cincinnati, the Pistons, the Knicks, the Philadelphia Warriors. We got to celebrate and have this holiday.

The guy who was at the head of all of it with Haskell was Red Auerbach. I got to touch shoulders every day—every day—with Red Auerbach. He would show me pointers and different things. And he said, “If you become eligible after you graduate from college, I’m going to draft you. You’re a good player.” I was like, “Holy Toledo! Red Auerbach’s saying that?” But he said it to other people. He spoke to Earl Lloyd and that’s how I became a Piston, because Early Lloyd was the chief scout for the Detroit Pistons. He said, “If Red Auerbach is going to draft this guy, we should take a look at him!” (laughs) He came to Philadelphia, he came to my home. You didn’t hear of NBA scouts going to people’s homes! He came to my home, met my mother. It was almost like a college recruiting thing. Then we drove together up to Allentown where I was playing—because I had dropped out of college—and he saw me play. He told my mother, “We’re going to draft him.” In those days you’d go, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. Everybody says that.” And that had happened! The Knicks came to see me play. The Cincinnati Royals came to see me play. So there was an awareness, but I thought I was going to be a Celtic with Auerbach, because that’s who I’d met at Kutsher’s. When I went to college in Oregon, that was the last guy connected to the NBA that had talked to me about being in the NBA. The NBA, at that time, was not a paragon of integration. You didn’t grow up as kids thinking that if we were good basketball players, we’re going to be in the NBA. That was just not the case. When it was brought to me, I was like, “Oh, okay.” I wasn’t poo-pooing it, but I wasn’t building my life around it either. Well, I get drafted by the Pistons and the story just goes from there.

Your story about being drafted is amazing, especially considering the pomp and circumstances being drafted now versus how you found you had been drafted.

(laughs) That’s one of my real joyful moments that I’ll have forever. Going to the Bronx to play a basketball game on the subway, and I picked up a newspaper—the evening newspaper, which I think was The New York Post. I’m reading through to see about the draft and I say, “Oh, no big surprise. They drafted Walt Bellamy out of Indiana.” He certainly was a cause célèbre and a great player. He should have been drafted number one. Number two, they drafted Tom Stith. Well I’m in New York, Tom Stith went to St. Bonaventure. He’s from Harlem—he’s a great player, an All-American. Then third, they drafted Larry Siegfried, from Cincinnati, who played with Jerry Lucas on that great Ohio State team they had down there with Havlicek and Bobby Knight. Come the fourth, I saw my name, Ray Scott. Ray Scott? I screamed! The people on the subway were startled. What I did—cause I’m from South Philly so I figure things out pretty good—I looked around like, who screamed like that? To this day, those people don’t know that it was me. (laughs) That was my pomp and circumstance.

But the story got better, because Earl Lloyd had me fly out to Detroit. It was like the arrival of a first round draft pick. That strikes me, there was no pomp, no circumstance. He took me to a club, he took me to dinner. We came back, and I remember asking him, “I didn’t get dessert at dinner. Can I get dessert? An apple pie a la mode?” He said, “Get dessert? You’re the number one draft pick! You can do anything you want. You can order a whole other meal.” (laughs) That was a big welcoming. I’m going like, “I’ve arrived. I’m really somebody.” I signed my contract the next day. I get twenty five thousand dollars for two years, and a thousand dollars of that contract is a bonus. Think about it. In 1961, flying back home in May or June, whatever that month was, with a thousand dollars in your pocket, when we would scuffle just to have two quarters in our pockets. Now today, those guys go home with bonuses of ten, fifteen million dollars wired to their accounts. But that was the way it was. There were a few guys in the NBA making what we would call big money. I would imagine Bob Cousy, Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, Oscar, Elgin, Bob Pettit, the usual suspects. But it was not a wealthy athlete’s league.

You had an amazing career as a coach but also you had an amazing run coaching your kids when they were growing up. That was such a fun part to read in your book.

That was absolutely a joy, because now I’m trained. Those girls got the best of Ray Scott as a coach, because I knew what I wanted to teach them, I knew how I wanted to teach them. That was just the happiest five years of coaching of my life. I couldn’t wait to get off work and get out to coach my girls. I would leave the office sky high. I brought in an assistant coach for my girls’ team, because I wanted to make sure that they had someone else to speak to, that they had someone they felt they could rely on too. I so enjoyed that. I was so happy in that five year period of coaching my girls, and I got to coach my daughters too. When they were at the high school, [my wife] Jennifer said, “You’re working two jobs.” (laughs)

And finally, what role has the library played in your life?

I grew up in a library. The library on Broad and Christian in South Philly was a haven. We learned to take out library books and get them back in on time. Then we had a main library in Center City Philadelphia that I went to do my homework on Sunday afternoons. I cut my teeth in libraries. That’s where I did my book reports. I think I got an A in a book report for The Corsican Brothers. That was one of my great reads. I read the classics and I did book reports on the classics. You’re thinking the book report might be for the teacher, but actually my book reports had to be for my mother. She wanted to make sure I read my classics, so I did The Three Musketeers, The Corsican Brothers, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, A Man Without a Country, Les Miserables. They were just great books. I just loved to read. I took care of my little brother. It was just cool. We were from the era where we were poor but we didn’t know we were poor, because we were surrounded by love and a good education. I had my father who adopted me for a short period of time. I still revel in that happiness of that time, that little four or five year period we had.

This interview has been edited for clarity.