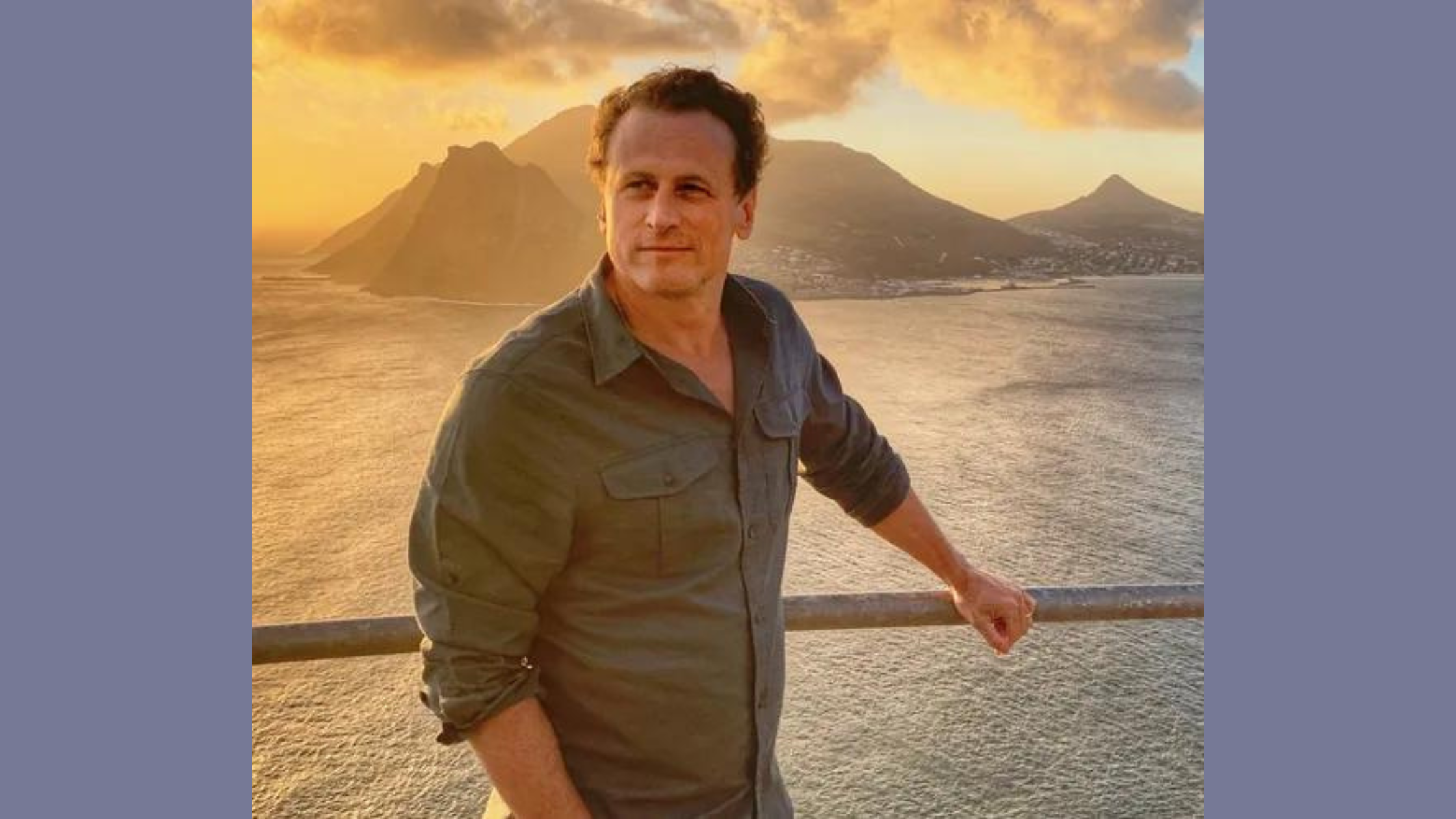

“The Movement is Already Out There” – David Moscow on Investigating Our Planet’s Interconnected Food Supply

For over four years, David Moscow has traveled the world, investigating the communities who produce our food sources on his acclaimed series “From Scratch.” Now the actor and producer has teamed up with his father, Joe Moscow, to write From Scratch: Adventures in Harvesting, Hunting, Fishing, and Foraging on a Fragile Planet. The book dives into the issues that arise on the television show: where does our food come from, who are the laborers that bring our food to our plate, and what are the economic and political forces at work around our food supply? Moscow gives the reader an insider’s look at food across our planet, as he harvests honey in Kenya, forages dune spinach in South Africa, and hunts wild game in Texas. The result is an illuminating look at the various economic, cultural, and political factors that surround our food supply chain, as well as a clarion call to changes we must make in order to save the planet.

How did this project come about? Where did this interest in investigating the source of your meals come from?

Well, there were two things going on in my life at the time. I was about to have a kid and I was sort of terrified. What do kids like? So I started thinking about the things I had enjoyed, the things that I remember that stand out in my mind. It always came back to being outside in the wilderness or an apple orchard or fishing with my grandpa. It was always these things that were in some ways food related. I remembered the joy of going pumpkin picking. I remembered the joy of going to farms and petting goats. I think that’s something—that kids gravitate to animals. [I remembered] all the things my mom and dad had done for me. They had a food co-op in the Bronx in the 70s. It’s actually funny, they came out here, and there’s a very fancy grocery store in Los Angeles called Erewhon. It makes Whole Foods look like the dollar store, it’s crazy. But Erewhon used to be a wholesaler for organic produce, so when my parents were running their food co-op they would get sacks of rice and sacks of grain in Erewhon’s burlap sacks. They were like, “Holy smokes!” Now it caters to the Kardashians and stuff like that.

On the other side of it, it was just prior to the 2016 election. Trump was really going after Hispanics—Mexicans in particular—and it seemed ludicrous—aside from dangerous and horrible—given how much American culture is Mexican, especially in California. The fact that all of our friends and family and neighbors were being attacked, meanwhile we’re eating tacos and the margarita is the most consumed cocktail in America. It just seemed really idiotic. At the time I was helping produce some digital content for the Bernie Sanders campaign with some of his surrogates. I had this idea, what if we did a feature documentary about the hard work that goes into all the meals that we eat, particularly tacos and margaritas? We could go down to Oaxaca and work with subsistence farmers growing corn to make masa to make tortillas. We could work with the jimadors and see what a tough job that is. Because food is so connective, right? No matter what people feel politically about one another, they’ll eat a pizza. (laughs) Everyone shares that.

It was just going to be this one-off documentary. My agents happened to represent Anthony Bourdain, and they came back and said, “[The production company] Zero Point Zero thinks that it would make for a really good TV show where you could investigate different food cultures each week, but still looking more at food producers than chefs and kitchens.” I think there are a lot of great shows out there that focus on what happens in the kitchen. They do it better than me, because they’re hosted by chefs. This turned into a layman’s perspective of food production. How do farms work? How do fisherpeople bring in fish?

What are some of the topics the book allowed you to explore more deeply than you could do in the cable series?

I remember this particular moment that stands out, and it sort of was the germination of the larger idea. I was in the Philippines, on a banca, which is the what the fisherpeople there use to fish. It’s a really unstable boat. We were out there for hours and we didn’t catch anything. I was making patis for Margarita Manzke’s restaurant Wildflower. Patis is a very foundational ingredient in Filipino cooking. The Philippines is a rice and fish culture, and we couldn’t catch anything. I asked the fisherman whether this was common and he said yes, that they were going out for days and not getting anything. That’s not something you can really dive into on a forty-two minute show on cable, because we’re there to make a meal, right? But it sparked our interest to do more research on it. It turns out that The Philippine Sea, The South-China Sea, is being incredibly overfished, but also has this really important, dangerous political mess that’s going on around the overfishing. China’s trying to expand into the sea for the fish. They’re building islands in the South China Sea. Some Filipino fishermen had just been killed a couple of weeks prior [to our arrival]. Suddenly we’re like, “Oh my goodness, this is really interesting and I had never heard about it. It would be really cool to write something deeper on that.”

Those kinds of things came up over and over again. We went to Finland. For the episode we were looking at how Finland is often seen as the happiest country in the world, they always win these awards. We did a surface glimpse on the show about how does food relate to that? But when you start pulling the thread there, Finnish history opens up, their engagement with the outdoors. In a lot of ways, we started learning about places that are doing things in a better way than the US. We saw a lot of places that are in deep trouble, South China Sea being one of them. Then we saw places like Finland, Iceland, and Costa Rica that are doing incredible things that the world could learn from. It was sort of bursting out of us, then how do we do it, right?

You do such a great job of communicating the historical background and political forces that are in play of each place that you visit. What was your research process like for the book?

There was an interesting thing that occurred in season one of the show. We sat down and did talking head interviews with an incredible group of experts—historians, professors, chefs, authors—around the topics of food and the histories of the different countries we were studying. [The producers] didn’t like the talking heads in the episodes. So we ended up having hours of amazing interviews that were just a transcription away from us using them. That was the first thing that we went back to. We transcribed all the interviews and we started pulling the threads. We both reached out to connections that we had. My dad runs a really neat podcast about ethics and education, so he’s connected to a lot of educators. My brother runs another podcast where he talks to economists. Through our personal network we were able to reach out [to different experts]. Leaning into the expertise of others is what we do on the show, and it’s what we really started doing with the book. Then each layer of the onion that you peel away reveals more, it becomes like you’re investigative journalists out there. I don’t know how many hours of fieldwork I did over the five years, but a pretty incredible amount of on the ground work, of seeing stuff firsthand, and then going and asking people, “Why is this happening?”

You write in the book that you wanted to go into this book “without romanticizing or looking for easy answers.” Can you talk about your philosophy in terms of how you approached these different countries and cultures with this project?

Individually, person to person, I’m always just super curious. I think that people open up. If you’re forcing them to toe your line of reasoning, then that stops pretty quickly. But if you go there and you’re really asking their thoughts on stuff, it opens like a flower. We all have ideas of how we want it to go, and then we feel like, “Okay, we’ve reached the conclusion.” Then my dad would lean over or I would lean over and say, “I think we need to go a little deeper on that because I think that’s incorrect.”

There was an example in Iceland where the fish stocks collapsed in the seventies and then they fixed it. They passed a law that every person and company has a quota for how much fish that they can harvest. The fish stocks are back and it’s incredible. That’s where I was done with that, at least on the TV show. As we were driving, there was some little thing our driver said, where he was like, “Yes, the fish are back, but it’s emptied all the fishing towns.” My first instinct was, “Oh, this guy’s grumpy because people don’t have jobs anymore, because they’re limiting the fish catch, right?” But that’s not what it is. I called a friend of mine who’s Icelandic and he introduced me to a food activist/TV producer who just made a show that’s the number one show in Iceland. It’s basically about how these eight families in Iceland have co-opted all of the fishing permits. These little towns where individual fisherman could go out and make a living have now sold their permits, will never get them back, and the whole of Iceland’s fish is owned by this very small group of people. The Icelandic people, after the economic collapse, voted to change the Constitution, which would make fish stocks back to being nationally held. They voted it in and these families have stepped in to halt the institution of the new Constitution. It’s been basically sitting in purgatory for five years now. Suddenly you’re getting into the economics around food and how you’ve got these probably billionaires who are using food or politics as a lever. It’s a much more complicated situation. If we hadn’t continued to ask questions, if [the driver] hadn’t been grumpily saying something under his breath, it would have ended there.

I’m curious about how you organized the book, since it seems that it’s out of order with the episodes of the show. How did you and your dad approach the narrative of the book? Why was the section on oysters the perfect way to kick off your book?

Oysters was New York, and New York is where I’m from. It always felt like one of the more personal stories I could tell, because I was talking about Long Island, where my dad was from, my first girlfriend was there. I could talk about the city a bit. We ended on pizza, which is also a very personal story. We kind of bookended it with my New York experiences. I’ve never written a book before, but having those two as the bookends, the framework, I knew it would be hard for me to mess up stories that are part of me. We did a six month process of winnowing down what it was that we wanted to tell. It was such a wonderful experience to be able to work with my dad on such a close, intellectually intimate level. It was really something else. It’s wonderful to have a reason to call your dad every morning and have a long, two-hour conversation. In many ways, it’s such a dream to be able to work with my dad. We spent a lot of time kicking around the ideas, mulling them over, and sending them back and forth.

There were some that just stood out. With the Philippines, we knew we wanted to talk about fishing, what’s going on in the South China Sea and the political ramifications of that, because that was one of the larger stories. We wanted to show places where things were going wrong and humans are really on the precipice of wiping out the planet and wiping out ourselves. At the same time we wanted to have alternatives, where if we listen to people who are doing things correctly, we can save ourselves, save the planet, and help our food systems and help the food producers. That’s another thing you see constantly, the economics around the people who bring the food to us is really devastating. There’s a lot of poverty around the world in agriculture.

We spent about six months winnowing it down. We tossed the ball back and forth and honed it until we had the general idea of what we wanted to do, and then the research would begin in earnest. It evolved. There are some chapters that we were very excited about that aren’t in there. Then there are a couple that made their way in. We also initially wrote some chapters that were really focused on one place and then we felt like there were other stories to tell, like around mushrooms. We told the Finnish mushroom story, but there’s also an incredible story going on in the Pacific Northwest. That came on near the end of our writing where we were like, “You know what? There are a few chapters we can add more by bringing in another part of the journey in another place.” Mushrooming in Finland and mushrooming in the United States are very different. In Washington State we went with this guy who said, “I can work dead end jobs that make me upset or I can be a mushroomer.” Both leave him in a precarious economic position, and yet he’s doing something he loves. He says, “When fall comes in the Pacific Northwest, and the rains and grey skies come, everyone gets really sad except for me. I’m about to go out and find some mushrooms. The mushrooms are coming! “

At the same time, when we met him he was living out of his van. If you juxtapose that with Finland, it was this very fancy hotelier who had been a model who came back to Finland to run the oldest hotel in Finland. It was super classy. I was going on a mushrooming tour in the Finnish woods and it’s like, “Wow.” And she was not unique. That’s the thing, the Finns mushroom! They go into the woods and they fish, they hunt, they mushroom, they go apple picking, and nature is really part of their lives.

I really appreciated how you and your dad showcased areas where people are affecting positive change. What do you want readers to come away from the book with?

I feel like the movement is already out there. I’m just sort of riding on the crest with other people of work that has been done before, like my parents did with co-oping in the seventies. There’s always been people who’ve known about this stuff, and I was really checked out. I was living in the New York and LA and had been unconsciously eating and consuming and purchasing. At the same time wondering, “Is this it? Is this what life is? Have I reached the peak?” (laughs) And questioning why there was, in a sense, this hollowness? I wasn’t working with my hands. I wasn’t working in the earth. One of the things I remember growing up is soil, and how east coast soil is so wet and rich and amazing. I had no interaction with the soil In the west coast at all.

Through the process of writing the book I coalesced some words to live by that I found for myself, and that is to eat less meat. Meat needs to move to the new appetizer portion of the plate or, frankly, just eat it less during the week. It should be an exciting thing when I have a piece of fish or steak or chicken. Sort of like how my mother, when she grew up in rural Montana, having meat on the plate was a big deal. When I do buy meat, I should pay a lot for it. It should affect my pocketbook, my wallet. I should pay a lot for it for a number of reasons. A, the animals should be treated humanely, the fish should be fished sustainably. B, the food producers need to be paid. Going out in the world there are groups of people who everyone agrees should earn more—teachers and nurses and food producers. That includes restaurant workers. Migrant workers need to be treated with respect and need to be paid. We need to make sure as consumers that that goes on. While we’re writing the book, suddenly COVID hits, and everyone’s seeing how important these people are.

We eat a lot less meat with every meal. We did a thumbnail sketch in the book that I’ve eaten around thirty thousand animals. I’m not unique in that way. My son, has come on a lot of these trips with me. He milked goats in Utah, he fished in Finland, he harvested eggs in Wyoming. He doesn’t like to eat animals as much, which is kind of cool. He’s not into it. He’s mostly vegetarian at this point. That’s affecting our dinner table, which is great. We eat a lot more vegetarian meals. Being conscious of what you’re consuming [is vital] because there’s a huge effect on the environment, there’s a huge effect on the humane treatment of animals, and there’s a huge effect on world politics. It’s important to stand our ground, to be conscious consumers as the world pushes us to be less and less conscious. This is important stuff. What we put on our plates is important stuff.