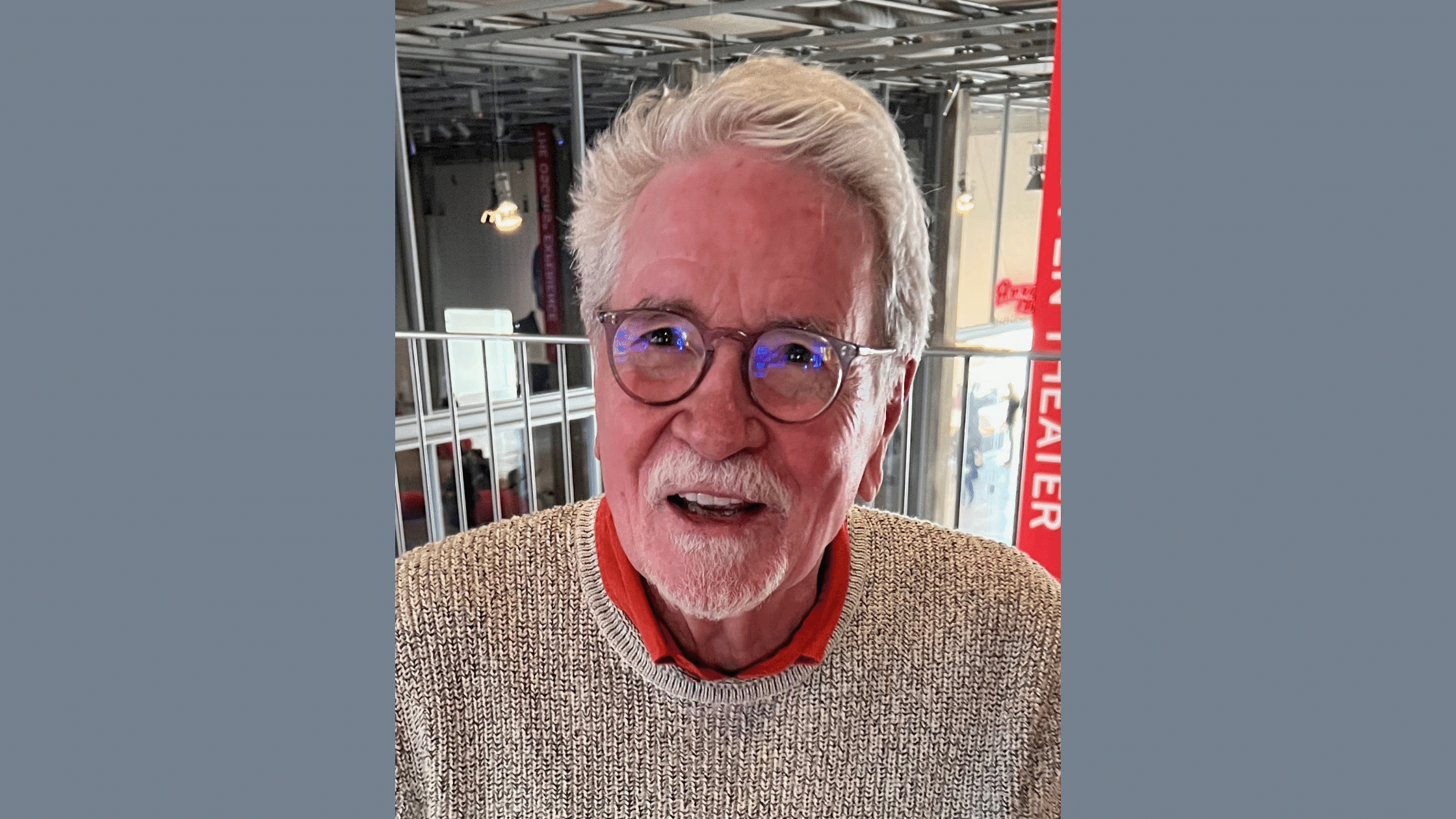

Bruce Davis Takes Readers Behind The Scenes On The Early Days of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Perhaps there’s no person better equipped to write a book exploring the tumultuous early years of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science’s existence than Bruce Davis. Davis worked at the Academy for three decades, and was its executive director for over twenty years. With The Academy and The Award, Davis has combined meticulous research with a dynamic narrative to reveal the compelling personalities of the actors, writers, directors, and filmmakers who comprised the Academy during its formative era. Along the way, Davis debunks some long held myths of Academy lore, including the true origins of Oscar’s name and the actual events of Bette Davis’ supposedly tempestuous term as the Academy’s President. An erudite and witty look at the Academy’s history, The Academy and The Award is a vital chronicle of film history that will be sought after by American history aficionados and film fanatics alike. Critics have lavished praise on the book, with U.S. News and World Report stating, “Film historians and others digging for a deeper vein of Oscar knowledge than mere trivia will turn up many nuggets in The Academy and the Award…Oscar would be lucky to have as keen and even-handed a historian as Davis to explore its next era.” Davis spoke with us about his extensive research, television’s influence on the Academy’s prospects, and how a chance remark by Gregory Peck caused Davis to change his office décor.

You worked at the Academy for thirty years, with over twenty years as its executive director. When did you first become aware of the need for this kind of book, documenting the Academy’s origins and early years of existence?

I guess I gradually became aware that there didn’t seem to be such a book, that it was hard to find information about the beginnings of the organization. I’d ask people, members didn’t really know much about it. There was a general blurriness about the [origins]. Most people could say something about Lous B. Mayer, but then it would dry up very quickly. I don’t know that there was a particular time where I thought, “Okay, I’m going to solve this problem. I’m going to write the book myself.” Certainly by the time I retired I had committed mentally to having a go at writing that book and finding out what had really gone on in the early years. I was extremely naïve about how long that would take. I literally had conversations with people where I said, “I think six months of research and then maybe a year to write the book.” (laughs) It took a lot longer than that. There was a lot more material to plow through. I stayed at it and I finally got a book out of it.

Can you talk about what your research process was like, considering all the primary sources you had access to?

I’m not sure anybody’s fascinated by this, but it was interesting to me! I had never written a book before and I had no idea what resources were available. I knew I was sitting on top of the [Margaret] Herrick Library, so there was stuff in there, but I hadn’t really looked at it in any way. I would go to the library every Wednesday, and the staff was perfectly happy to bring me tons of boxes full of very early material. Part of the job was just to see what’s out there. It took me a couple of years just to go through a lot of this early stuff and decide where are the threads that make this a narrative about this organization? What kinds of things do I need to put to the side?

It was primarily those resources from the Herrick Library that they had been saving since actually before the organization was formed. I found minutes from pick-up meetings from before they decided they would make an Academy. I had the invaluable resource of the Board of Governors minutes for all of the meetings of the governors themselves, and from some of the key committees that decide various things. Those had actually sat just outside my office the whole time I was there [at the Academy]. Unless a particular issue came up that would send you back to a decision that was made in 1947 or something, you didn’t really read those, but now I did. There were lots of surprising things. There were a couple of things that were tantalizing because you wanted them to say just a little more. Give me more explanation of why the Academy suddenly decided to add supporting actor categories to the roster of categories, because it just shows up one year. They just do it! There’s no discussion of it in the Board. It was a good idea, but who was pushing it? There’s always some back and forth when somebody suggests a new category. There were things where I wish the secretary of the Academy at the time had been a little more longwinded about why something happened but still, in most areas, it was illuminating to see what the actual discussions had been and who’s making what argument on which side. That was a rich resource for me.

What were some the misconceptions about the origins of the Academy that your research uncovered or corrected?

I think one of the main misapprehensions, although it’s not entirely wrong, is that Lous B. Mayer decided that the industry needed such an organization to fend off the unionization that was becoming more and more prevalent in the country during the teens. He didn’t want that coming to the movie industry, so he formed this organization as a guardian of the purity of the film industry. He certainly did propose it, but what became clear as I was reading early minutes of the meetings, that isn’t what attracted artists to the organization. They weren’t going to join some paternalistic organization that was dedicated to keeping their salaries down. They didn’t see it as a labor organization. They saw it as a way to gain respectability for the art form they were working in. Movies, as late as 1927, weren’t really ranked in people’s minds among the major artistic forms. They clearly had become that by that time, but the artists felt they weren’t ranked with the writers, painters, musicians and whatnot that the world recognized as artists. Again and again, they talk about that being something that a pantheon organization that brought the most accomplished people in the various fields of moviemaking together, that somehow this could work to impress on the public that this was an artistic form, and an important one.

Something that really surprised me was how precarious the Academy’s existence was in its first few decades. In your opinion, what was the Academy’s inflection point in terms of its survival as the institution we know it as now?

Well that’s a question with a pretty clear answer, actually. Like you, I had no idea—even after working there for a couple of decades—I had never really grasped how impoverished the organization was throughout its early history and how nearly it came to folding on a couple of different occasions. It was something they worried about all the time: “Other than dues, how can we raise money to do all these wonderful projects that we have in mind?” When you think about it, it’s not so surprising really. First of all they formed the organization in 1927. A couple of years later, boom! Here comes the depression. They’re having to get the organization launched at a time when even movie stars were having trouble scraping together the kind of funds that they’d gotten used to. That was a problem. They had to keep going to the producer’s organization for any kind of even minor funding that they were looking for. They had no sense of income. The other odd thing was that even after they got one, they didn’t recognize it. The show, as you know, was broadcast on radio for quite a few years before television came and they got no income! It never occurred to anybody to charge for broadcasting the Academy Awards, but they didn’t! I had never understood that. Getting back to your question, what is the point at which things get better? Well, it’s television. They resisted it mightily. They thought it was undignified. The studios saw television as a huge enemy. It certainly was a huge rival in terms of the fight for the public’s attention, but finally they realized they weren’t going to get funding in any other way. They swallowed hard and signed up with a network. The coffers weren’t flooded immediately, but very soon they began to have a more comfortable existence because they had a regular source of income.

Your book covers so many people who were instrumental in the Academy’s success and survival, but one I’m particularly interested in is Margaret Herrick, who was its executive director for twenty-five years. Can you talk about what kind of person she was?

Yes, to the extent that I was able to get people to talk about that. I don’t mean that they were withholding, but her time was just far enough ago that there weren’t many people around who ever worked with her. She had died by the time I had been hired by the organization. There were still a few people around who had worked with her and remembered her, but by the time I got ready to write a book, a lot of those people were gone too. So I had trouble getting firsthand information about her, personal impressions. I had a couple of people who said interesting things and, of course, I had all of her writings and memos and letters to people.

She was a person who came very early to the Academy. In 1931, she married kind of a second executive on the staff at the time, and she became Margaret Gledhill for a while, since his name was Gledhill. She wasn’t on the staff herself for a while, but she did start building the magnificent Academy library even before she was on the paid staff. The existence of the library very much owes to her early work there. Then when war came, her husband went off to Washington to serve in the Army Signal Corps. He talked the Board into hiring her on a temporary basis in his absence. That’s kind of surprising. I say in the book, the headline in Variety was “Acad Hires Femme Boss.” That was so unusual, that was the headline—that a woman would be put in charge of what was, by that time, a well-known and important organization. But it was supposed to be temporary, so when he came back he was expecting to pick up his job. Well, that didn’t happen. She had impressed the Board strongly enough that when he returned they didn’t give him his job back, which the GI Bill guaranteed people who went away. They had to offer to pay him a year’s salary to make him go away. She was called the Executive Secretary at first, and then got the same title I had, Executive Director. She was good at it. She loved the organization, she worked hard at it, she knew the heads of the studios, and she knew the artists that were making the films. She was a huge influence on the development of the Academy and she was very much right there actually doing some of the negotiations with the studios when the television years came around.

She seemed to be a larger than life figure. In the book you get a sense of the drama of replacing her husband, because he had requested a divorce while he was away, right?

He was positioned in DC. He wrote Margaret and said, “I’ve fallen in love with this other woman, and I’d like a divorce.” She said, “Meh, okay.” (laughs) I think that had something to do with him not getting the job back, because it would have left her out in the cold. But I never found a piece of paper where anybody’s saying, “He’s behaved badly, we have to get rid of him.” I don’t know what the considerations were. I couldn’t find anything that told me, so I’m speculating that they realized during his absence that they had access to maybe a more dynamic figure to run the organization.

The early days of the Academy are entwined with huge events of American history. You write about how Better Davis accepted her presidency right before the attack on Pearl Harbor and how the Academy had to navigate the HUAC hearings.

Everybody did in those days. That was an interesting era. The governors tried to keep away from the McCarthy considerations as much as they could, but nobody could step aside and say, “We’re not going to deal with that.” Guys were being fingered by all sorts of people. If you had belonged to a left-wing organization at any point in your career that was likely to come out in the papers, and it would be very hard for you to get work in motion pictures. That was tricky. They didn’t navigate it absolutely successfully. There were a couple of people who were denied Oscars, at least for a time, who should have received them. It was a nasty era. The Academy very much, as you say, got caught up in it.

I was really struck by the chapter on the Blacklist and how you were able to pull in your own experience when Elia Kazan received his honorary Oscar in 1999.

I had some trouble deciding whether I could justify putting that in, because timewise, it was beyond the scope of my book. It was interesting, not just because I was there and got to see the arguments and fighting firsthand, but it did kind of put a period on that whole unfortunate era, so I thought that justified putting it in the book.

You also write about several people who served as president of the Academy. Reading the book, it feels like Gregory Peck ushered the Academy into a new era of success. Can you talk about what kind of a president he was and what made him so successful?

There again, I was thinking, “Okay, I didn’t say I’m going to write this book from 1927 to 1955 or anything.” Clearly Peck was later. I had talked about [Frank] Capra’s era, and if you had to pick a most important Academy president, I think it had to be Capra. Although I didn’t say it in the book, I think the Gregory Peck presidency was the second most important. He agreed to do it and took it very seriously. Not all of his enterprises were successful. He made some very bitter enemies when he attempted to thin the ranks of the Academy. He thought we had too many people who weren’t even working in the motion picture area anymore. He raised the whole question of whether Academy membership should be a lifetime honor or did you have to somehow show that you were still making movies? But it was a question worth bringing up, and I think you can make a legitimate answer on either side. He spent a lot of time talking to various groups and speaking for the Academy, and he always took the noblest side of whatever issue he was speaking on.

I loved Larry Gelbart’s quote about him that you have in the book: “Whenever Greg expresses a preference for something…it comes out in that voice that carries the weight of Ahab, King David, and Atticus Finch, and it’s all that the rest of us can do not to stand up and salute.”

He did sound like that! It was true. I’ll tell you, there was an evening when there had been some kind of meeting in the board room that I didn’t go to because I had something else pressing. Greg came out of the meeting, and it’s like 7:30, 8 o’clock in the evening by that time. He was surprised to see a light on in my office. He came wandering in. He’d been looking at a row of big, framed pictures from different movies on the wall. When he came in he made a very concerned face. He said, “Bruce, I see the ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ picture there.” I said, “Yeah, we thought that was a good choice.” He said, “Why didn’t you put up the fella that won the award?” (laughs) I hadn’t thought about it that way, but that was his year. Atticus Finch did beat out D.H. Lawrence. He made it a joke, but he still noticed. Needless to say, by the next time he came to a meeting at the Academy there was a portrait of Atticus Finch up there, just in case it wasn’t entirely a joke. (laughs)

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tags: Bruce Davis