Melissa Mogollon On The Joy Of Writing Angry Teenage Girls

When readers first meet Luciana in Melissa Mogollon’s Oye, a natural disaster has upended the high school senior’s life. Hurricane Irma has forced her family to evacuate Miami, and Luciana is stuck in a car with her mother, an eternally optimistic swimming instructor who has never fully acknowledged that Luciana has come out. To make matters worse, it falls upon Luciana to convince her glamorous grandmother, Abue, to join them in fleeing the hurricane. Yet Abue, a charismatic entertainer who spends her time juggling online romances and singing at nursing homes, has other plans. Luciana soon finds herself mediating her mother and grandmother’s contentious interactions when Abue moves in with Luciana’s family after receiving a sobering medical diagnosis. Now roommates with her grandmother, Luciana is shocked when Abue lets down her guard and reveals family secrets from her childhood in Colombia. Oye is a tender multigenerational family saga that celebrates storytelling in its many forms. Electric Literature hailed it as “a funny and heartfelt exploration of growing up, resilience, sisterhood, and finding your path” while Debutiful described it as “a swoon-worthy family saga that will make you fall in love with the characters.” Mogollon spoke about falling in love with a character’s voice, the joy of writing angry teenage girls, and nerding out about craft.

The novel is set up as a series of one-sided conversations that Luciana is having with her older sister, Mari. It’s so fun to be immersed in Luciana’s voice. Can you talk about how you arrived at that way of telling the story?

It was the first structure I tried for the book. It started as a short story in grad school. At the time, I was really taken by one-way communication. I was writing a lot of short story drafts as voicemail transcripts or as one-way phone calls. It was never two people talking in dialogue, it was always just one person. Looking back, I think it’s because I would find characters that I loved and I just adored hearing their voice for a long time uninterrupted. I just loved being in their voice.

At first, I had the grandma and Mari, the older sister, also talking, but I always was having the most fun when I was in Luciana’s voice. I always had an excuse to not write when I wasn’t in her chapters. I would have to go change my tires or something ridiculous. (laughs) I realized that Luciana’s voice was the only one that was putting my butt in a chair to really work on this.

Personally, I liked how angry she was. I love angry teenage girls. As a former angry teenage girl, it was very cathartic to be able to say a lot of things that I didn’t [say back then] through her voice. It was fun and totally selfish for me. Once I realized how fun it was, I wondered if I could tell a whole story with traditional elements of storytelling—with plot, character, suspense, irony, arcs—through what a girl would just organically say to her sister. It kind of gamified novel writing for me. It gave the book this energy that I didn’t know was there before, where I was like, “Is this possible? I have no idea!” That’s what pushed me to set out to figure it out. With every chapter, I would be like, “Okay, well, that one’s done. But can I do it with this next one?” I knew, narrative wise, what the reader needed in each chapter, and I was like, “How can I get the reader there by the end of the chapter just based on what Luciana is saying?” It became this total nerd exploration of craft, and I thought, “If I can do it, it’s gonna be really cool.”

There was a whole journey with it. I had people look at it. Some people told me, “Take her off the phone.” Because I love words and writing, I was like, “Sure, let me try this out.” I tried the first 100 pages in first person and then in third person. I had other people talking, other people on the phone. I tried it all to feel, “Now I know for sure I want to just keep her on the phone on her own, by herself, just her voice.” The other ones didn’t feel as fun for me. Her rage, her humor, her heart, and her grief were most present when she got to tell her own story. It felt the most real on the page, so I stayed with her. I wanted to be able to say there are different forms of storytelling. There are just so many other things that are possible that we don’t even think about.

It’s exciting to hear you talk about testing out other ways of telling the story to conclude that you were right.

It’s not like I was, “Yes, I was right along.” (laughs) But it was more like, “No one can say anything. I’ll have peace in my heart at night.” I’m not going to read a critique or hear something be like, “Damn, I should have tried that,” because I’ll feel good knowing that I did. The limits that the form gave me in the beginning were difficult. I had to figure out how to work around them, but then it just made me a more intentional, creative writer. I realized by the end that the limits of form pushed me in ways that I wouldn’t have pushed myself before as a writer. It was exciting, energizing, and eye-opening.

One thing I was struck by was how layered all the relationships are in the book. The relationships among Luciana, her sister, mother, and grandmother are very distinct and constantly in flux. What was appealing to you about showing the complexities of all these different family dynamics?

The first sentence that comes to mind, and I’ve never even verbalized this in any other interview, is that “crazy comes in all different colors.” I feel like there’s the archetype of the crazy Latina woman in books. While all these women certainly have a level of rage and drama that is particular to Latino culture, they’re all so different, but they all steal the scene in their own way. They all could have novels written about them as the main characters. I loved the idea of bringing all these lions together in a room and watching them.

I also wanted to show how much they love each other and the different ways they’re willing to fight for each other and with each other. I think that intimacy was really true in my family and my neighbors and my friends’ families growing up in Miami as full immigrant households. I thought that was really singular to that kind of multi-generational Latino household. Even today if I’m raising my voice to someone at work—I work in Rhode Island—I think I’m having a regular conversation, and they’re like, “Whoa, we don’t need to fight about this.” I’m like, “I’m not fighting!” (laughs) Essentially, I wanted to show what is a regular Tuesday in South Florida for people.

Tasha Sandoval’s recent essay “Toward A New Abuelita Canon” singled out Abue as an example of a new way of thinking about abuelitas in popular literature. In creating Abue, did you have any goals about writing a woman that maybe had not been represented so far in literature?

Definitely a reason why I was so taken and in love with the grandmother character is because she essentially didn’t want to be a grandmother. At every chance she got, she defied what people expected of her. Not out of rebellion or wanting to prove a point, but that was genuinely who she was. She was just fighting to make space for who she was, which is she wanted these things that people didn’t want her to have. I thought it was really cool that she was from one generation, and her granddaughter is in this other generation, but they are essentially fighting for the same things. These two individuals couldn’t be more different, but what they are fighting for is the same thing, which was just to be heard and to be left alone, essentially to let them live.

It was depressing and beautiful, all in the same breath, that they could be however many decades apart and still fighting the same fight. It was really sad for the grandmother to have to still be doing this fight. But I wanted Luciana to see, “Oh my gosh, I’m going to be doing this my whole life if I don’t chane. I’m just going to do me. I’m not going to think about other people.” In that way, the grandmother’s fight had more meaning and value in giving Luciana a perspective, almost like it wasn’t all for nothing,

I really love the grandmother. My own grandmother in real life was totally the inspiration. Her story is different, but the essence of the character is really similar. I love that in a world where women were told to be a certain way, that this grandmother character really just wanted to wear sequins and mesh, to have her boobs done and her butt done. She had no intention of wanting to be nurturing or proper. She just wanted to live, because she didn’t get to when she was younger. I thought that was important to say, maybe not directly, because Latina grandmothers are a certain way in literature. I hadn’t thought about that until I did those interviews and they pointed that out. I thought that was so special and meaningful for me to be able to contribute to that. But I was simply writing her story the same way I was just writing Luciana’s story. They just happen to be these types of people. But yeah, long story short, Abue was definitely inspired by my own grandmother, who did not want to be a grandmother either. I always was so in love with that. I loved that she was honest in a culture that really pushed avoidance and hiding and just conforming. She stood out to me in that way, and I thought it would be perfect for the book,

The book begins with two epigraphs. One is a lyric from a Fall Out Boy song, “Is this more than you bargained for yet,” and the other, “Entre broma y broma, la verdad se asoma,” you attribute to “everybody’s mother.” How did you land on those as being the perfect quotes to kick off your book?

Thank you for asking about them, because I love them so much. I always knew that the Fall Out Boy lyric was going to be the opening, because that was personal. I absolutely adore “Sugar, We’re Going Down.” I love Fall Out Boy and I love that whole genre of music. But more importantly, I really, really love that line, “Is this more than you bargained for yet?” Even though it’s not what it means in the song, I just loved the idea of this almost God-like figure coming down to Luciana and being like, “Is this it? Are you tapping out now?” I felt that feeling of being overwhelmed was really integral to Luciana. She doesn’t have time to figure out who she is or what she wants, because all these women around her are going crazy. She just wants her grandmother to live. To me that’s so central to the book. Luciana just wants to be a teenager, and she feels she has to step into this caretaking role because she believes no one around her is thinking clearly. She thinks, “Well, if I don’t step in, my grandmother’s going to die.”

I loved the teenage angst that’s in that Fall Out Boy song, and I played it a lot while I was writing. I played a lot of that music while I was writing. I have a whole playlist for it. It was so important for me for the rage to be front and center in this book. That quote, to me, confronts the rage, which I really liked.

“Entre broma y broma, la verdad se asoma” means “in between every joke, the truth peeks out,” which I also thought was just brilliant. A lot of the pain and the heartbreak in the book comes through the humor. I love the visual of in between the jokes being thrown at this group of women, the little face of truth is peeking out, being like, “No, but she kind of means that.” I couldn’t find who said that at all or to attribute it to, so I thought “everyone’s mother” would be funny, because it’s true. It’s a saying that we hear often.

You’re also a high school teacher. Luciana’s voice is so specific and funny, and I think readers will fall in love with it. I was wondering if working with high school students informs your writing.

I liked going on tour and meeting with readers and talking about the book, because you realize so much. I was on stage answering a question where someone was like, “Was it easier for you to write because you work with high schoolers?” I had never thought about that, because my students are so different than Luciana, and Luciana is so different than them. I never made the connection. But what I did make the connection with is my unusually vast patience for teenagers. (laughs) That’s why I was able to write the book, and that’s why I’m able to teach. But I think it also comes from the appreciation for the young voice. I love hearing what kids have to say. I always have. It’s probably why I spent almost 400 pages with a teenager, and it’s definitely why I spend my days with teenagers.

It informs my writing in the way that I continue to be shocked and surprised and humbled and amazed and awed every day at the things teenagers say and do, in the same way I probably was with Luciana as I was writing. There’s just an energy. I’m curious. I want to know the next thing they have to say, because I find them to be so ridiculous, in the most loving and tender way. They’re just beginning to be beaten down by life. They’re not so afraid yet, although they’re very afraid in other ways. They’re still building their voice as teenagers, but I like that they’re more honest than adults. I think that’s why I like Luciana, and I love teaching. I get to teach creative writing, so I get to really, really hear their voice, and I get to help them build their voice because it’s there. They’re just uncovering it.

What role has the library played in your life?

Our public library was maybe a mile from our middle school. I walked to school, so I walked straight to the library after school every day for three years. Not only was it a great refuge after school—because otherwise a lot of us would just be sitting at home doing nothing or getting into trouble—it was amazing to be around books constantly. And the programs that the library offered! My mom was always enrolling me in Tai Chi, origami making, or arepa making, whatever after school program they had for kids. It was one of the places that I learned how to use a computer, which was also really exciting.

But I will always remember—even before that in elementary school—I totally did the opposite of what I was supposed to. I would go to the young adult fiction section, and I would pick out all the pink books, or anything that looked glittery or shiny. I would stack them all up and check them out. Then my mom would say, “You’re not reading all those. You can’t get them,” and I would say, “Yes, I am.” Then I would read them all to prove her wrong. (laughs) But mostly I didn’t care what was in them. I just loved that the colors were so beautiful. It usually ended up transferring to something I was excited about, like fashion or teenage girl drama, which I was attracted to at the time. Clearly, I haven’t changed. (laughs) I grew up reading The Private series, the Clique series. I was in love with The Series Of Unfortunate Events series. I loved those covers. They weren’t pink, but they had really cool drawings. I was a huge reader. I lost it somewhat in high school based on the books I was being assigned. But I credit my love for romance and summer camp novels in elementary and middle school to my high reading comp, which totally helped me graduate.

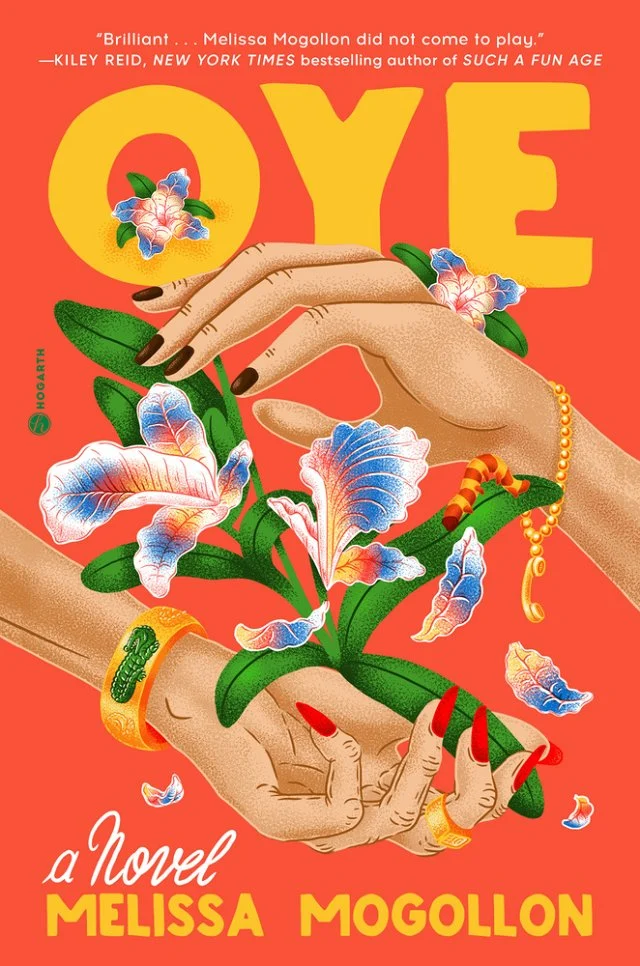

Speaking of striking book covers, the cover of Oye is so beautiful. Did you have any input into it?

I love it so much. I still can’t believe they were able to put it together. My editor and I came up with a list of symbols that we thought would work well. I thought two hands might be fun. One could be the grandma, one could be the granddaughter, and they would have some symbols around them. The orchid on the cover is the national flower of Columbia. The petals have the colors of the flag, which are yellow, red and blue. That’s not explicit anywhere, but I love to tell people if they ask about the cover. The orchid is a symbol of Colombia, and also orchids are really delicate, but really strong. They survive in rainforests on the side of trees. I liked that duality of strength and fragility all in one, which reminded me a lot of the grandmother. My grandmother’s name in real life was Alba, and that’s actually a type of orchid in Colombia. I wanted an alligator somewhere on the cover, because I’m a big animal lover. I grew up in Florida, and wanted to signal that this is a Florida book too. They put “Oye” in the ring at the bottom of the grandma’s hand. I hadn’t thought of that. It was really amazing that they came up with all these details just from symbols I thought would be cool on the cover.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Tags: lgbt youth, LGBTQIA, Melissa Mogollon, YA Books, young adult books