Entrepreneurial Leadership in Public Libraries

In the last decade, public libraries have faced drastic changes due to technological advances (e.g., smartphones and e-readers), and the changing information-seeking behavior of library users. More recently, public libraries are facing additional changes brought on by the continued economic downturn, which has forced many of them to undergo budget cuts that have resulted in the reduction of facilities, staff, hours, and resources. Yet public library use has increased as more people are coming to the library to take advantage of the services and resources offered. Public libraries function in a climate where budget cuts and the realignment of services are a reality. They have to find a balance between providing core services and offering new ones that meet the information needs of their communities.

James Neal, vice president for information services and university librarian at Columbia University, addresses what academic libraries should be doing in a changing environment. According to him, regardless of the type of library in which the person functions, librarians “must pursue strategic thinking and action, fiscal agility, and creative approaches to the development of collections and services and to the expansion of markets.”1 It may be that the directors of some public libraries, as some academic library directors have done, are exploring new ways of generating revenue streams. One way of doing this is by engaging in entrepreneurial activities in which a library expands its “interest in the organization of business operations to create new income streams for the organization.”2 Yet, no study has investigated whether public library directors engage in entrepreneurial leadership as a means of generating revenue in new ways.

The purpose of this study is to examine library directors’ views of such leadership, the types of entrepreneurial opportunities they are pursuing, and whether they are planning additional endeavors.

It aims to illustrate the benefits and challenges of entrepreneurial leadership, further the understanding of entrepreneurial leadership in public library settings, and offer insight into the types of entrepreneurial activities occurring in public libraries. The directors who are already engaged in entrepreneurial leadership will want to see what others are doing. This information may also be of interest to Friends of the Library groups and library trustees so that they can get a better sense of their supporting roles to libraries pursuing entrepreneurial activities. In addition, leadership institutes and professional associations will benefit from an understanding of how entrepreneurial leadership in public libraries is viewed. They can develop leadership education and training in the area of entrepreneurial leadership. Finally, this study will also be of interest to those offering continuing education since it may be beneficial for library managers to take classes or workshops in entrepreneurship.

Literature Review

The field of entrepreneurship is a relatively new area of interdisciplinary study.3 Busenitz et al.,4 who examined journals that cover entrepreneurship, see it as an emerging field of study within management. The traditional view of an entrepreneur is associated with business, and often entrepreneurs are defined as individuals who start their own small business.5 However, “entrepreneurship can involve nonprofit organizations.”6

A component found in some definitions of entrepreneurship is that entrepreneurs create something new and add value.7 Another component is innovation.8 Several theorists and researchers mention the pursuit or exploitation of opportunities in their work on entrepreneurship,9 and Darling and Beebe describe entrepreneurship as “essentially about breaking new ground, going beyond the known, and creating a new future within an organizational setting.”10 Vecchio argues that “studies of entrepreneurs have not yet offered a convincing profile of factors that clearly make entrepreneurs different from others.”11 As a result, he believes entrepreneurship is part of the study of leadership.

Thoughts on Entrepreneurial Leadership

According to Powell, “Entrepreneurial leadership stems from the concepts of leadership and entrepreneurship.”12 Like with entrepreneurship, there is no clearly established and agreed upon definition of such leadership. It is very much a concept still in the nascent stages.13 Some research finds an overlap between entrepreneurship and leadership.14 For Cogliser and Bingham, vision, influence (both of followers and of a larger constituency), planning, and “leading innovative/creative people” are relevant to entrepreneurial leadership.15

Eggers and Leahy found thirty-four leadership skills as critical to entrepreneurial leaders. The top five are: (1) financial management, (2) communication, (3) motivation of others, (4) vision, and (5) self-motivation.16 Vision is often mentioned in entrepreneurial leadership research. Gupta, MacMillan, and Surie add vision as a component in their definition of entrepreneurial leadership:

Leadership that creates visionary scenarios that are used to assemble and mobilize a “supporting cast” of participants who become committed by the vision to the discovery and exploitation of strategic value creation. This definition emphasizes the challenge of mobilizing the resources and gaining the commitment required for value creation that the entrepreneurial leader faces, which involves creating a vision and a cast of supporters capable of enacting that vision.17

The research of Darling, Keeffe, and Ross focuses on what it takes to be a successful entrepreneurial leader, namely “leading through direct involvement, a process that creates value for organizational stakeholders by bringing together a unique innovation and package of resources to respond to a recognized opportunity.”18 Being a successful entrepreneurial leader involves promoting new activities, being creative, innovative, and constantly adapting to change. In addition, it is having the ability to take advantage effectively of opportunities and to motivate people to be involved in taking advantage of those opportunities.19

Entrepreneurial Leadership and Libraries

There is minimal research on entrepreneurial leadership in libraries. Most writings on entrepreneurship in library and information science are either informative or opinion essays; they do not comprise research. However, there are a couple of examples such as Kilgour’s20 examination of entrepreneurial librarians between 1880 and 1970, and Nijboer’s21 presentation of how libraries can engage in cultural entrepreneurship. Some writings provide examples of revenue-generating areas in libraries such as cafés.22 Another example is by Neal, who discusses the need for academic libraries to embrace the entrepreneurial spirit and to “create new income streams for the organization.”23 DeVries points out that, while librarians engage in discovering, evaluating, and exploiting opportunities to create new services, these activities are not labeled as entrepreneurship.24

More Focus on the Definition

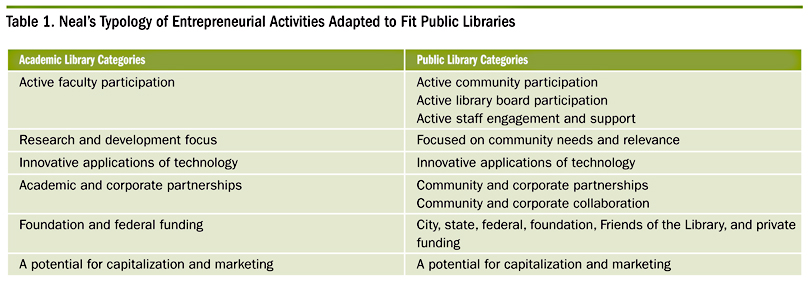

Shane and Venkataraman define entrepreneurship as the process of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities to create goods or services,25 and Darling, Keeffe, and Ross view entrepreneurial leadership as “leading, through direct involvement, a process that creates value for organizational stakeholders by bringing together a unique innovation and package of resources to respond to a recognized opportunity.”26 Neal identifies three objectives of entrepreneurial business initiatives: “to produce new income to benefit library collections and services, to learn through these activities, and to apply these lessons to library programs.”27 He also identifies several characteristics that “reflect an entrepreneurial culture and an innovative spirit.” These characteristics portray his typology for entrepreneurial activity in an academic library setting. The characteristics are: “active faculty participation, a research and development focus, innovative applications of technology, academic and corporate partnerships, foundation and federal funding, and a potential for capitalization and marketing.”28 These characteristics can be adapted to fit a public library setting (see table 1). Shane and Venkataraman’s definition (paired with Darling, Keeffe, and Ross’ definition as well as Neal’s idea of generating new revenue streams for libraries) serves as a framework for investigating entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial activities in public libraries.

Research Questions

This study focuses on investigating whether public library directors engage in entrepreneurial leadership as a means of generating revenue in new ways. The following questions are probed:

- How do public library directors define entrepreneurial leadership? Do they share the same definition or certain common characteristics in the definitions?

- How well does Neal’s general typology of entrepreneurial activity (see table 1) apply to public libraries?

- What types of entrepreneurial activities are they engaging in and for how long? What is the focus of such activities?

- To what extent do they view entrepreneurial activities as a way to generate revenue streams?

- Do they have future plans for engaging in additional entrepreneurial activities? What are they?

Procedures

Peter Hernon, professor of the Simmons College PhD Managerial Leadership in the Information Professions (MLIP) program, asked Luis Herrera, city librarian for the City and County of San Francisco, and Jan Sanders, director of libraries and information services for the City of Pasadena, to identify public library directors engaged in entrepreneurial activities other than the library cafés. While operating a café is one type of entrepreneurial activity, it is too common as a sole basis for selection of participants. Herrera and Sanders provided some suggestions. To this list, Professor Hernon added one public library director. To further expand this list, the investigator shared it with Maureen Sullivan and Camilla Alire, also professors of practice in the MLIP program, and asked them for additional names. The investigator used the snowball technique; she asked each director interviewed to suggest potential participants. In order to preserve confidentiality, she asked them to contact those individuals and inquire whether or not they would be willing to participate. In addition to this, the investigator asked the aforementioned individuals to review Neal’s altered table (see table 1) and comment on it. The investigator made changes as requested by the panel of five national leaders.

Between November 2011 and July 2012, telephone interviews were conducted with study participants. The investigator contacted them by email, letting them know about the study and encouraging them to participate. The email contained a letter explaining the study and why their participation matters. The directors were assured of confidentiality, and, for the purposes of the study and reporting findings, they were identified by a letter from the alphabet to conceal their identity. The names of their institutions also remained confidential so that they would not be identified by association with their institutions. Those that agreed to participate received a list of open-ended questions that the investigator asked during the telephone interview. The participants had approximately one week to review the questions and prepare any notes before the telephone interview.

The interview form was reviewed by Hernon (as well as by Herrera and Sanders) in the fall of 2011 for clarity (reliability) and the capture of research questions and the theoretical framework (internal validity). Before the interview questions were finalized, the Simmons MLIP 2011 Cohort pre-tested them. During the pre-test, the wording of the questions was examined for clarity and some questions were rewritten based on the comments.

Participants

Of the twelve directors initially identified as entrepreneurial leaders, nine participated in the study. By utilizing the snowballing technique, the investigator came across thirteen additional names. It is worth noting that some names came up several times. Out of those thirteen, there was a director identified that had since retired and could not be contacted as well as another director who had moved from a public library to an academic library, and was thus no longer qualified to participate in the study. Following study procedures, the investigator was only able to contact six directors from the list of thirteen names acquired by utilizing the snowball technique, and only three consented to participate. The study had a total of twelve participants out of eighteen directors contacted for a participation rate of 66.7 percent.

Definition

The participants were provided with a definition of entrepreneurial leadership: “creating a vision and leading the organization through the process of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities to generate revenue streams that reinforce existing services or lead to new services and/or funding models.” Four participants were satisfied with it. One director added that “Entrepreneurial leaders also work on maximizing the investment that exists already.” The other participants wanted to change part of the definition. Two participants were concerned about the word exploitation and thought it was harsh. They preferred realization or implementation. Another participant thought the definition strongly focused on revenue streams, but should move beyond just a financial focus. One director preferred a focus on working with and leading people, and another found the definition to be “overly reductive” pointing out that there are “smaller opportunities which can be called entrepreneurial [such as] discovering things about human beings and their needs.” It was noted that any mention of partnerships was missing from the definition and that new or additional revenue streams could not completely replace tax funding for libraries; the majority of library funding will always come from taxpayers. Six participants agreed that entrepreneurial leadership was about constantly evaluating how the library is doing and looking for new opportunities and partnerships.

Neal’s Typology

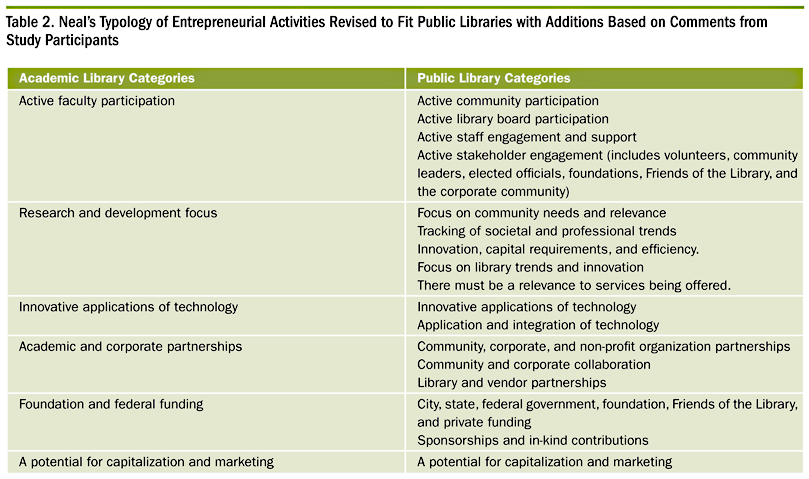

After reviewing table 1, four participants agreed that it was fine as is. The other eight participants suggested additions (see table 2). For the category “active community participation, active library board participation, and active staff engagement and support,” one director pointed out that there is a difference between active and focused participation and that having an active library board does not equal having an entrepreneurial organization. This director also mentioned that it is important to value innovation and an entrepreneurial spirit in an organization and recognize it when it happens in order to preserve it. For the category “focus on community needs and relevance” a director felt that this was the most important activity, adding that an entrepreneurial library setting is one that demonstrates return on investment.

When discussing the category of “innovative applications of technology,” a director mentioned that library users come in with varying knowledge and comfort levels with technology, which makes it necessary for the public library to innovate at a level consistent with the skills and comfort levels of the general public. This could limit or slow the extent to which a library is involved in entrepreneurial activities. Another director recommended using lean principles of process to promote efficiency and effectiveness for various applications of technology. The idea behind this is that libraries are more reflective of an entrepreneurial environment if they have efficient and streamlined processes. A different director stated that public libraries have to be “very cognizant about bridging the digital divide” and that “the public library offers the opportunity for a large number of residents to get free computer training and free online connectivity.” This comment served as a way for this director to clarify the meaning of the category.

For the category of “community and corporate collaboration” a director emphasized the importance of defining partnerships in such a way that moves the organization forward and in a way that aligns with the library’s strategic plan. This director advised library leadership not to do something that does not fit with the direction the library is going and that does not make sense for that library. There were no additions to the category of “foundation and federal funding,” which lists types of funding, and none to the category of “potential for capitalization and marketing.” It was noted that, “Public libraries are always seeking opportunities to use the strength of numbers to negotiate a better value for products and services.”

Types, Focus, and Length of Entrepreneurial Activities

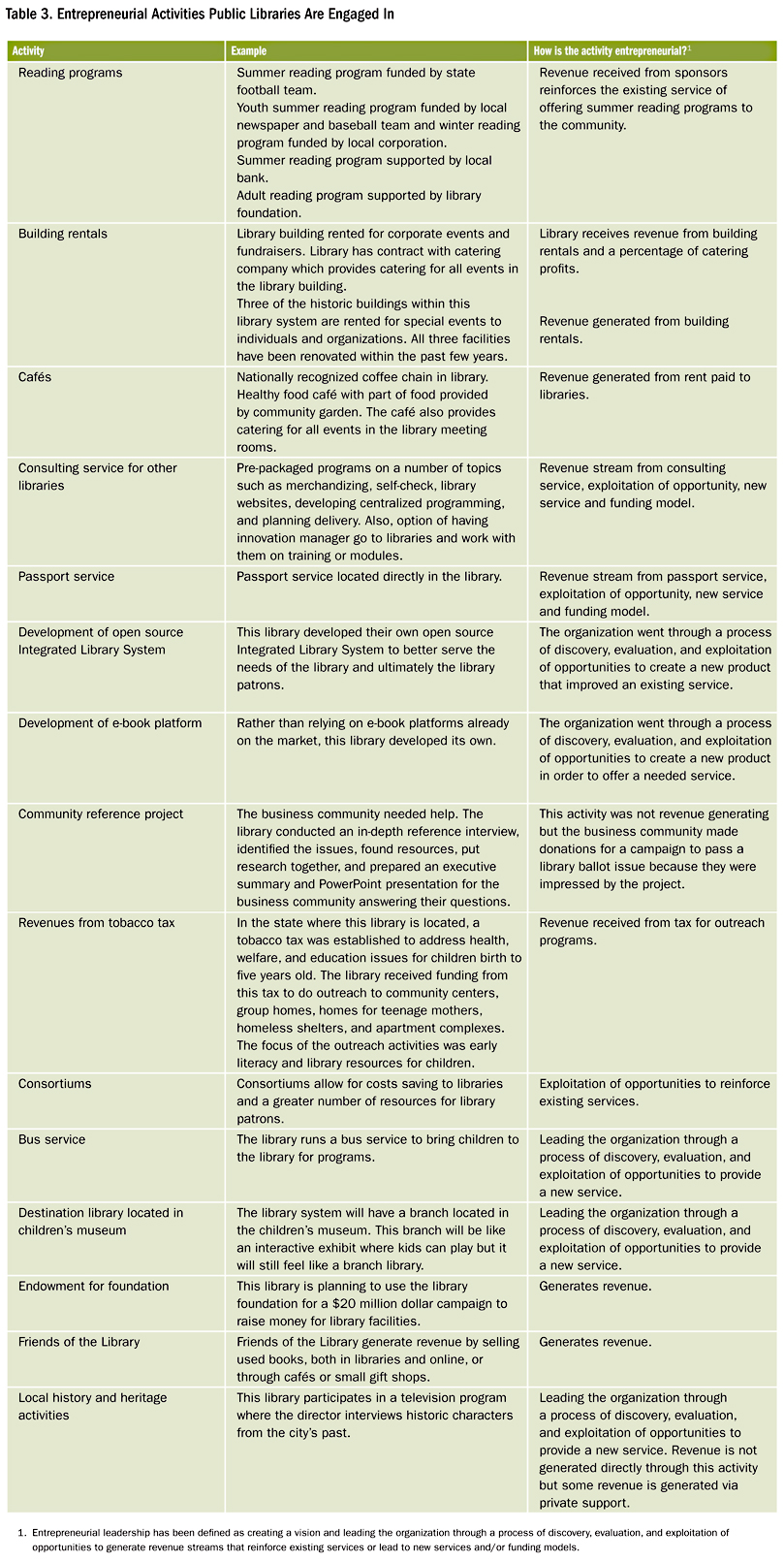

The participants engaged in a variety of activities they consider entrepreneurial (see table 3 below). The focus of the activities can be grouped into four categories: (1) traditional library services funded by outside support, (2) activities that directly generate revenue, (3) activities that do not generate revenue but provide a new product or service, and (4) activities that are non-revenue generating but add value. The length of time that participants have been engaged in entrepreneurial activities varies. The longest amount of time is thirty years and that is for membership in a library consortium. The shortest amount of time engaged in an activity is two years, and the activities for that time frame are: planning for a library branch in a children’s museum, revenue from a tobacco tax, and the e-book platform.

Revenue Streams

Seven activities were mentioned as revenue generating, with some producing more revenue than others. The activities identified as revenue generating are:

- building rentals for various events,

- cafés,

- consulting service for other libraries,

- passport service,

- revenues from tobacco tax,

- endowment for library foundation, and

- Friends of the Library fundraising activities.

Three other activities generated revenue indirectly. The first activity is summer reading programs, which libraries received funding for, from entities such as sports teams or local newspapers. The second is a community reference project which did not generate revenue itself. However, the business community made donations for a campaign to pass a library ballot issue because they were impressed with the project. Lastly, a community history project was not revenue-generating but the library gained private support from the exposure through activities such as the television interviews. Some directors mentioned activities as entrepreneurial though they did not generate revenue. They preferred sharing the ideas with other libraries to benefit the greater library community and library users, rather than charging for them.

Future Entrepreneurial Activities

All of the library directors plan to pursue entrepreneurial activities in the future. Some already have specific plans for types of activities they wish to pursue while others are not exactly sure what those activities will be. Those that did not have specific activities planned believe libraries have to constantly look for ways to improve daily operations and for new opportunities and partnerships that may generate revenue. One director stated that new activities for the library should be based on the library staying relevant and meeting the specific needs of the library’s community. This was reflected by other directors who stated that any entrepreneurial activities that a library is engaged in must make sense for that library and for that community. One director commented that libraries should diversify revenue streams in order to offset library vulnerability when difficult economic times arise.

A participant has plans for creating “co-creation” spaces at the main library for entrepreneurial people to come and meet with clients or brainstorm with other entrepreneurs. This director also mentioned piloting customized spaces within a library. The director of another library has a wealth of historical information and photographs, and wants to put together a coffee table book of historical photographs, have it published, and made available for sale at the library. This director is also interested in having posters, postcards, and other paraphernalia that speak to the history of the city available for sale. The library owns items that are locked away yet they could be used in a revenue-generating way. A sculpture (of a girl on a bench reading to a dog) was commissioned by a donor at the request of another library director. The sculpture was very popular in this library and the director is considering partnering with the sculptor to promote the sale of similar sculptures to other libraries. The library would get a commission fee for every sculpture purchased.

A director plans to expand on activities that the library is already doing with some variation and depth. This library partnered with the inner city hospital and healthcare foundation to deliver information through library branches. This director sees a need for the library to organize information and have it readily available before people come looking for it because people trust libraries in ways that they do not trust other institutions. A participant is planning to allow customers to pay fines online or via self-check stations with the option to round up fines to the nearest dollar. This extra money would go to the library endowment campaign and has the potential to generate $100,000 or more per year. One director labeled her future activities as “political entrepreneurship” explaining that in a few years the library will have to go back to voters and needs a two-thirds vote to continue the specialized tax dedicated to the library. The will be the third time that the library will be on the ballot and there are a lot of politics involved in getting the city council to put this on the ballot. The director of another library plans to take a lead in acquiring or developing a volunteer software matching process. In his community, public entities are looking for more public engagement.

General Comments

When asked if they had any additional comments, one participant stated that a library director “can’t be a good leader without being entrepreneurial.” Another participant thought that libraries have a lot of potential to engage in entrepreneurial activities. One director emphasized that what is entrepreneurial in one community may not be in another. This tied to the opinion stated by several directors that any entrepreneurial activities the library is engaged in have to be relevant to the community. The director of one library suggested that a library must be cognizant of the customer’s needs and that directors should determine if there is a way to create revenue for the library while also meeting a community need.

A lot of change is happening in libraries today and libraries have to adapt. According to a participant, “Just by adapting the principle of entrepreneurship, they [libraries] become more flexible and open and this is what we have to be.” Another participant mentioned that to be entrepreneurial in the kind of circumstances we are in today, libraries: “(1) must not forget the traditional library, (2) introduce people to the rare and finer pleasures of reading and civilization, and (3) not be afraid of change.”

One director thought that entrepreneurial leadership is something that needs to be pervasive within the organization. Another director echoed this by stating that if you want to have an entrepreneurial organization, you have to show that you value that. You have to define it for your staff and reward it when it happens. A different director’s comment on entrepreneurial leadership was “It doesn’t even seem to be something special anymore. It is a basic and general expectation of any director that wants to be in today’s world. The needs are too great for communities. Entrepreneurial leadership is almost a requirement.” However, another participant thought that getting library directors to think of entrepreneurial leadership as a concept and plan things based on being entrepreneurial is a challenge because, traditionally, library directors are not trained to think this way. Finally, another participant saw entrepreneurial leadership as an opportunity. He said, “Entrepreneurial leadership is both an incredible opportunity and a danger. If we are willing to try new things that get at our mission it is a fantastic time to be a librarian. A focus on civic engagement and community engagement deepens our connections. By chasing new things you can run yourself away from the purpose or mission of your organization.”

Discussion

Traditionally, when one thinks of revenue-generating organizations, one does not include libraries in that category. It was not surprising that the participants reacted most negatively to the phrasing “exploitation of opportunities” in the definition of entrepreneurial leadership provided for this study. That phrasing comes from definitions of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial leadership found in business-related research, although some agree that entrepreneurship can extend to nonprofit organizations.29 The other portion of the definition that some participants had trouble with was “generate revenue streams,” because that has not traditionally been viewed as a major role for libraries and is something mostly associated with businesses. In describing the types of entrepreneurial activities that they were engaged in, the participants that did not generate direct revenue streams from their activities still fit the definition of entrepreneurial leadership because they created something new that adds value30 and/or because their activities involve innovation.31

Entrepreneurial activities that participants engaged in were varied and the activities ranged from the fairly recent to those that have been going on for a number of years. Even with confidentiality guaranteed, several participants were not comfortable providing estimates of how much revenue is generated by the activities. This makes it difficult to determine a range or come up with an average. It was not unexpected that several directors were interested in entrepreneurial activities but not concerned with generating revenue. Rather, they were willing to share their achievements with other libraries. From the study findings, it is clear that with innovative projects like the integrated library system (ILS) and e-book platform,32 there was a focus on the greater good for libraries and library users rather than generating profits. This fits with the idea of libraries not being revenue generators and was partially reflected by participant comments on the definition of entrepreneurial leadership that was provided.

All participants were interested in pursuing entrepreneurial activities in the future, even the participants that did not have a clear idea of what those activities may be. The participants agreed that there was a need for libraries to be entrepreneurial, to pursue new and innovative activities, and to embrace change as a way to survive. None of the participants seemed satisfied with the status quo and that is, perhaps, why they were identified as entrepreneurial leaders.

Out of the entrepreneurial activities libraries are engaging in, some do stand out as more extreme than others. The three that stand out are the consulting service, the development of an ILS, and the development of the e-book platform. The consulting activity is revenue generating and provides a service that is typically not provided by libraries. In the case of the development of an ILS and the e-book platform, both directors were not satisfied with the products or models that dominate the library market and decided to explore options on their own that would better serve their needs. It will be interesting to see if similar activities will become more common for libraries in the future.

Further research on entrepreneurial leadership in public libraries should examine whether entrepreneurial activities are becoming more prevalent. Another topic to be addressed is leading change in an organization. How are directors that are engaged in entrepreneurial activities preparing their organization for those activities? Many of the activities mentioned in this study are large enough in scope to need organizational support and they are not activities that a director can accomplish alone. In this study entrepreneurial leadership was defined as: “creating a vision and leading the organization through the process of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities to generate revenue streams that reinforce existing services or lead to new services and/or funding models.” This definition should be reexamined in the future.

Conclusion

Library entrepreneurial activities are diverse and many can be applied on a smaller or larger scale. As noted in the study, when exploring types of entrepreneurial activities, it is essential to find something that aligns with the library’s strategic plan and something that makes sense for the community the library is located in. All study participants have plans for engaging in further entrepreneurial activities. Some have a clear idea of what those activities will be while others are still exploring the possibilities. There is agreement that library directors need a more entrepreneurial mindset and that there needs to be more discussion of what it means to be an entrepreneurial leader. In the future, there will be a need for more entrepreneurial leaders that are forward thinking and that are constantly looking for ways to improve the library if libraries are to remain relevant and survive in this climate of constant change and uncertainty.

As change remains the only constant in public libraries and as they continue to operate in an economic downturn, it becomes necessary for libraries to reexamine how to stay relevant and explore innovation and the idea of diversifying revenue streams to decrease vulnerability. Still faced with an uncertain future, entrepreneurial leadership may become more of a necessity in the public library of the future.

Some types of entrepreneurial activities are revenue generating while others are innovative, yet do not generate revenue. One thing is clear: all the activities add value to their respective libraries whether it is through a product or service the library offers, direct revenue, or indirect funds that

find their way to the library based on the activities the library is engaged in.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- James G. Neal, “The Entrepreneurial Imperative: Advancing from Incremental to Radical Change in the Academic Library,” portal: Libraries and the Academy 1, no. 1 (Jan. 2001): 1.

- Ibid., 10.

- Claudia Cogliser and Keith Brigham, “The Intersection of Leadership and Entrepreneurship: Mutual Lessons to be Learned,” Leadership Quarterly 14, no.6 (Dec. 2004): 771-779; Lloyd Fernald Jr., George Solomon, and Ayman Tarabishy, “A New Paradigm: Entrepreneurial Leadership,” Southern Business Review 30, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 1-10; Donald Kuratko, “Entrepreneurial Leadership in the 21st Century,” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 13, no. 4 (2007): 1-11.

- Lowell Busenitz et al., “Entrepreneurship Research in Emergence: Past Trends and Future Directions,” Journal of Management 29, no. 3 (June 2003): 285-308.

- Satyabir Bhattacharyya, “Entrepreneurship and Innovation: How Leadership Style Makes the Difference?” Vikalpa: The Journal for Decision Makers 31, no.1 (Jan. 2006): 107-115; Peter Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Practice and Principles (New York: Harper & Row, 1985).

- William Gartner, “What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Entrepreneurship?” Journal of Business Venturing 5, no. 1 (Jan. 1990): 27.

- Bhattacharyya, “Entrepreneurship and Innovation.”

- Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Howard Stevenson and J. Carlos Jarillo, “A Paradigm of Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial Management,” Strategic Management Journal 11, no. 5 (Summer 1990): 17-27.

- Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Rita McGrath and Ian MacMillan, The Entrepreneurial Mindset (Boston: Harvard Business School Pr., 2000); Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (New York: Harper, 1950); Stevenson and Jarillo, “A Paradigm of Entrepreneurship.”

- John Darling and Steven Beebe, “Enhancing Entrepreneurial Leadership: A Focus on Key Communication Priorities,” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 20, no. 2 (spring 2007): 152.

- Robert Vecchio, “Entrepreneurship and Leadership: Common Trends and Common Threads.” Human Resource Management Review 13, no. 2 (Summer 2003): 322.

- Freda Powell, The Impact of Mentoring and Social Networks On the Entrepreneurial Leadership Characteristics, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Overall Business Success of Women Who Own Small Government Contracting Businesses (Doctoral dissertation 2010). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (No. 3447891): 36.

- Stephen Kempster and Jason Cope, “Learning to Lead in the Entrepreneurial Context,” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 16, no. 1 (2010): 9.

- Cogliser and Brigham, “The Intersection of Leadership and Entrepreneurship”; Fernald Jr., Solomon, and Tarabishy, “A New Paradigm.”

- Cogliser and Brigham, “The Intersection of Leadership and Entrepreneurship,” 777.

- John Eggers and Kim Leahy, “Entrepreneurial Leadership,” Business Quarterly 59, no. 4 (summer 1995): 71.

- Vipin Gupta, Ian MacMillan, and Gita Surie, “Entrepreneurial Leadership: Developing and Measuring a Cross-Cultural Construct,” Journal of Business Venturing 19, no. 2 (Mar. 2004): 242.

- John Darling, Michael Keeffe, and John Ross, “Entrepreneurial Leadership Strategies and Values: Keys to Operational Excellence,” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 20, no. 1 (Jan. 2007): 42.

- Ibid.

- Frederick Kilgour, “Entrepreneurial Leadership,” Library Trends 40, no. 3 (Jan. 1992): 457-74.

- Jelke Nijboer, “Cultural Entrepreneurship in Libraries,” New Library World 107, no. 9 (Sept. 2006): 434-43.

- Beth Dempsey, “Cashing in on Service,” Library Journal 129, no. 18 (Nov. 2004): 38-41.

- Neal, “The Entrepreneurial Imperative.”

- JoAnn DeVries, “Entrepreneurial Librarians: Embracing Innovation and Motivation,” Science & Technology Libraries 24, no. 1 (Mar. 2003): 209-10.

- Scott Shane and Sankaran Venkataraman, “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research,” The Academy of Management Review 25, no. 1 (Jan. 2000): 217-26.

- Darling, Keeffe, and Ross, “Entrepreneurial Leadership Strategies and Values.”

- Neal, “The Entrepreneurial Imperative,” 11.

- Ibid., 8.

- Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Gartner, “What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Entrepreneurship?”

- Bhattacharyya, “Entrepreneurship and Innovation?”; Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

- Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Stevenson and Jarillo, “A Paradigm of Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial Management.”

- The library has collaborated directly with publishers to offer e-books to its patrons via the library catalog. The library purchases the titles directly from the publishers rather than an aggregator and manages its own content.

Tags: leadership