Reaching Senior Patrons in the Digitized Library

According to the most recent available figures from the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.2 percent of the population is age 65 or older with an additional 5.7 percent turning 65 within the next five years.1 This segment of the American population is an important part of the library’s user group, and one which we must consider as society and the public library become more digital.

The Issue

In Western countries, the older a person is, the less likely it is that he or she uses technologies such as mobile phones and computers.2 According to the PEW Internet & American Life Project, only 53 percent of Americans age 65 or older (hereafter referred to as “seniors”) use the Internet, compared to 87 percent of all American adults.3 Among seniors older than 75, this number drops to 34 percent. Of those seniors who use the web, 70 percent do so on a typical day. This shows that “[o]nce they are given the tools and training needed to start using the Internet, [seniors] become fervent users of the technology.”4 However, this is only possible for seniors with access to appropriate tools and training. Training in particular can be an issue; a 2010 study showed that 68 percent of seniors above the age of 75 felt that they would need help before they could start using the Internet.5

With the rise of e-books in both society and libraries, it is also important to look at seniors’ use of e-readers. The numbers here are lower than those for Internet use: 11 percent of all seniors and 5 percent of seniors over 75 have e-readers, compared to 18 percent of all American adults. Tablet ownership is even lower: only 8 percent of seniors overall and 3 percent of seniors over 75 have tablets,

compared to 18 percent of all American adults.6

The Reasons

Why are so many seniors infrequent technology users? A look at the recent research can provide some answers to this difficult question. Researchers in the United Kingdom conducted discussion groups during a nine-month computer training program to learn why seniors felt they experienced problems with computers. They found seven reasons why seniors felt they had trouble learning how to use a computer:

- alienation from the new technologies;

- a lack of expertise with technology from previous experiences;

- feeling pressured to learn it rather than wanting to themselves;

- fear of doing something wrong and having bad consequences;

- feeling too old because “[by] the time I will really know the computer I will be too old to bother with it”;

- being too busy; and

- not having a use for it.7

These findings are consistent with other research on the topic. A 2001 study found that seniors expressed very similar challenges towards technology, including:

- overcoming fear;

- remembering what to do;

- difficulty understanding terminology;

- anxiety caused by having to find documents, files, and programs that have disappeared;

- learning how to get to the items they need; and

- keeping up with new technology.8

A 2010 article found that computer terms and acronyms are harder for seniors to relate to than for younger people, which could be another reason why seniors may feel they are too old to learn such technology.9 Studies cited in a 2009 article by Ruth Abbey and Sarah Hyde show that many seniors do not find the Internet relevant to their lives because they’ve lived so long without it.10 Another study cited by Abbey and Hyde shows that some seniors are concerned about a lack of privacy on the Internet, which is another aspect of anxiety or fear as previously described.11

Abbey and Hyde themselves studied the use of mobile phones and email by politically active seniors, resulting in findings about their abilities and attitudes. The study found that twenty-four of the twenty-six respondents used email, and that both of those who abstained from using email for their political activities did so because they felt they didn’t have the required skills. Since they did use email for other communication, this indicates a lack of skill with navigating the Internet or using electronic mailing lists. Another respondent indicated that he had trouble sorting through all the information available to form a cohesive and accurate whole.12

The Survey

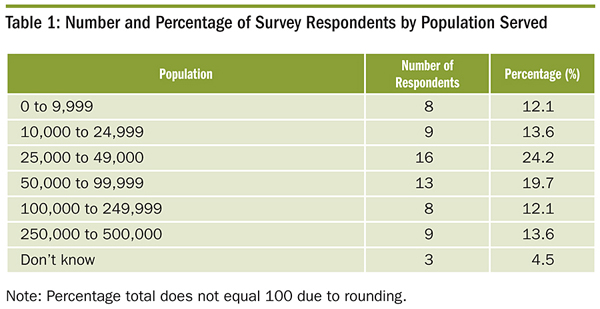

In light of so many U.S. seniors’ limited use of digital technologies, we decided to look into the kinds of digital resources and services that U.S. public libraries offer and to study how public libraries aid seniors in learning how to use new technologies. We created an online survey to learn about librarians’ perspectives on the technology needs of seniors and the services they are providing. We conducted the survey using the web-based survey platform Qualtrics and recruited respondents through eight library electronic mailing lists. The survey was active between January 16 and February 18, 2013, and yielded sixty-six complete responses. Respondents came from all across North America and served populations which ranged from less than 10,000 to more than 500,000, with the largest number of respondents serving smaller to middle-sized communities (see table 1).

The librarians who participated in the survey indicated extensive use of the Internet in their libraries. Ninety-eight percent reported that their libraries have a website, 92 percent said that they have accounts on social-networking sites, and 41 percent indicated that they have reviews from Goodreads or LibraryThing incorporated into their OPACs. While not asked specifically about digital databases, fourteen respondents (21 percent) volunteered that their libraries also offer subscription databases. It is likely that the number of libraries which offer this service is much larger.

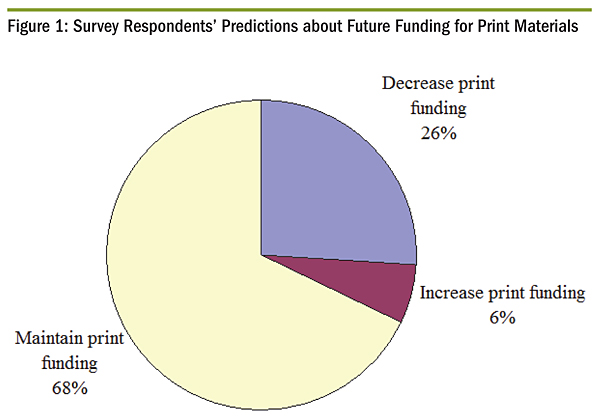

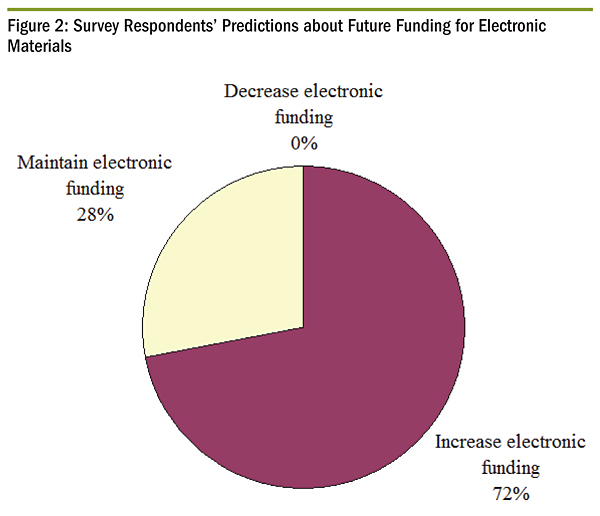

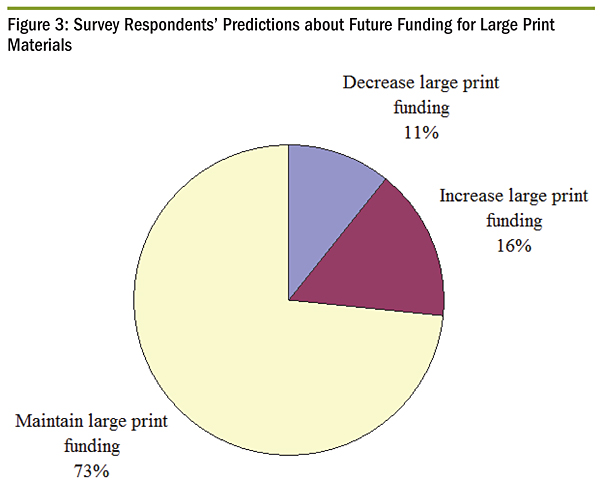

E-books are also a large part of today’s libraries, as indicated by our survey. Ninety-five percent of respondents indicated that their libraries offer e-books to patrons, and 45 percent also loan e-readers. In addition, 72 percent of librarians surveyed expect funding for electronic materials to increase in the near future, and 26 percent expect funding for print materials to decrease (see figures 1-3). While only 11 percent of respondents predicted a decrease in funding for large print (while 16 percent expected an increase in funding), the ability of e-readers to turn any book into a large print book will expand the selection of available books for seniors and other patrons with vision difficulties if the patrons know how to use the technology.

However, funding shortages are keeping many librarians from being able to fulfill community demand for e-books. As one Nevada librarian wrote: “We just don’t have enough funding to put into purchasing e-books, so we have a large wait list for the ones we do have.”

Technology Training in the Library

Our survey also asked respondents about their senior patrons’ technology needs, and about the types of formal and informal instruction they provide. Thirty-six (55 percent) of the librarians in our survey indicated that their libraries offer computer classes. Of these, 53 percent offer classes in computer basics, 47 percent offer classes in Internet basics, and 44 percent offer classes in Microsoft Office. Other classes include social media (25 percent), digital photos (8 percent), genealogy (8 percent), and job hunting (11 percent). Only 8 percent of libraries offered classes in using electronic databases. Some libraries offer an extensive range of classes, such as a New Jersey library offering classes in “startup with the Internet, Google Search Tips, Websites for Book Lovers, iPad & Android Apps, Word, Excel, Facebook, Uploading & Editing Photos, email, downloading e-books, and more.” Forty-one percent of libraries surveyed also offer e-reader training, 59 percent of which is conducted via classes.

Some libraries offer specific classes for seniors, while others welcome seniors in their general computer classes. Of the librarians we surveyed, 33 percent indicated that their libraries offer computer classes specifically for seniors. Of the other 66 percent who do not have senior-specific classes, 36 percent of the classes are attended mostly by seniors. As one librarian wrote, “[Although our classes] and tutoring are offered to all, it works out that virtually all the sessions we do are with library users age 55+, as that age group more frequently ask for assistance in these areas.” Five libraries also conduct computer training at local senior centers. For instance, one Alabama librarian wrote that her library “offered basic computing, one-on-one peer training sessions in conjunction with a local senior center as part of a grant project. At the end of the grant project, we were unable to continue running the sessions, but branched out with other senior organizations in the area to serve specific populations with targeted training sessions most requested by members of the organization.”

Computer classes are not the only way libraries help their patrons learn how to use technology. Twenty-seven percent of librarians surveyed indicated that their libraries offer one-on-one technology training appointments and 9 percent indicated that they offer drop-in sessions. For example, an Ohio library offers “walk-in help with e-book readers, tablets, and other such devices. Customers can make an appointment for hour-long individual help sessions. We [also] have e-book readers, tablets, and other such devices for staff so that we can hone our skills to best help our customers.” In Michigan, another library invites “National Honor Society members [to] come in to get service hours by giving one-on-one assistance, which we tend to gear towards seniors.”

Another popular tech-training program was the “technology sandbox,” in which the library provides seniors with a range of sample devices to try out and to practice using. A library in New York “sets out the most popular devices (Kindles, Nooks, iPads) so that patrons can test them and get a feel for how they work. We offer as sistance with the use of the device, including how to check out library e-books and transfer them to the device.”

A common theme among survey respondents was the importance of offering entry-level instruction for seniors. A librarian in Alabama expressed that “[m]ostly, seniors in our area are interested in learning to use computers to access online social services and communicate with family members.” Another librarian from Mississippi explained how her library caters towards the needs of these seniors: “Most other classes offered in our community begin at too advanced a level. Our class assumes nothing, and we have a 1:2 student-instructor ratio (largely filled through volunteers) to guarantee LOTS of individual help. [We offer] how-to-use classes for common devices, such as iPads, e-readers, and email.”

Barriers to Technology Training

Libraries that can offer services such as those at the Mississippi library mentioned in the previous paragraph are few and far between. Librarians in our survey indicated that they wish they could offer more technology training to their patrons, but they face many barriers. The most frequently identified barriers involved limited staff time and knowledge, as 33 percent of librarians surveyed indicated this as an issue. For example, a Connecticut librarian explained that “We don’t have enough staff time to provide around-the-clock intensive e-book help. Whenever we have an open drop-in session, we are swamped.” Even in libraries which employ a larger number of people, limited technology knowledge amongst staff is a barrier to instruction. A California librarian wrote that “some of our librarians are just as fearful of new technology as our patrons. Lack of training for staff members, and lack of desire to learn, are major barriers.”

Library space and available technology to use for training was also identified as a problem for 11 percent of our survey population. A large library in New York, for example, “just expanded our Cyber Center to triple its former size, and it still doesn’t seem to be enough to meet the demand.” Similarly, at a mid-sized library in California, “It would be useful to have a quiet area for training. Many training sessions take place in the library itself, which does not allow for normal/loud speaking (especially for seniors who are hearing impaired).”

Twenty percent of librarians specifically indicated that money was a barrier to offering technology training for patrons. With more money in the budget, librarians would be able to hire more staff, train staff on technologies, and invest in more computers and spaces to use for training sessions. One funding source libraries might consider is grants. The Foundation Center offers a Foundation Directory Online (http://fconline.foundationcenter.org) which allows users to search for foundations which fund in particular areas, such as technology or libraries. While this is a subscription database, it can also be used for free at Cooperating Collections locations across the country (http://foundationcenter.org/fin).

In addition to grants, libraries can take advantage of local resources to assist in technology training. Several of the libraries surveyed indicated the use of volunteers as teachers in their technology classes, and this can be an excellent way to supplement staff instructors. Libraries can partner with local schools and colleges to set up a community service program. While volunteers will need to be trained in teaching methods, often these younger individuals will already have a foundation in how to use technologies and libraries can take advantage of this knowledge. Additionally, libraries can consider fundraising drives to support the purchase of additional technologies to use for training purposes.

Best Practices

Taken as a whole, the survey results indicate that these public libraries provide a range of technology resources and service for seniors, but there is more they could be doing to help reduce the age-based technology gap. We can learn from the existing research on technology instruction and other technology-related library services about best practices for helping seniors become more knowledgeable and more comfortable with digital technologies. Together, these studies show us that best practices for library technology instruction for seniors include:

1. Small class sizes. In a study done with patrons at two Australian libraries, researchers found that adult library users prefer learning about technology in small classes with a maximum of six students per class and a face-to-face teacher.13 Small class sizes offer teachers the opportunity to pay individual attention to each learner, which can alleviate the seniors’ anxieties about doing something wrong.

2. Guidelines and tip sheets.14 Providing written guides for seniors to take home helps them remember what to do, which helps alleviate the fear of forgetting what they’ve learned in class.

3. Post-instruction contacts. Once the class is over, senior library users would like to see individualized help for specific problems that they encounter and additional self-help aids made available, now that they know enough to be able to follow them.15 Having someone to contact with problems after the class is over helps the learners figure out what to do when layouts change and things they used to understand disappear.

4. Hands-on training. It is also important that classes take place in a space where seniors can interact with the technology they are learning to use. Research shows that people retain what they learn better when they are engaged with their learning—or in other words, “doing something” rather than passively listening to someone lecture or viewing a PowerPoint.16 Being able to use the tools during instruction is especially important when working with technology.

5. Social/emotional support. Collaborative, hands-on training fosters a supportive learning environment where seniors can struggle with the technology and observe others struggling with it, which creates an understanding that they are not alone. The encouragement they receive from both their fellow learners and their teachers helps relieve anxieties.17 Patience, encouragement, and respect from the teacher also help with this.18

6. Individualized attention. Even if teachers are well-versed in the issues that seniors face when it comes to technology, they need to make sure to engage with the individual learners. Asking learners to describe their previous experiences and encouraging them to mention any problems they have with the material will help teachers tailor instruction to meet each particular class’s needs.19 In addition, understanding the learner’s self-perceptions and prior skills allows the teacher to aid learners in building upon this experience, boosting selfconfidence with early successes.20

We should note that the current research focuses on teaching computer skills, not other technological skills. Cassell, Bamdas, and Bryan also suggest e-book clinics facilitated by library staff which use both visual and hands-on demonstrations to teach patrons how to download e-books and use the library software on their devices, but they do not describe them further.21 While we lack e-reader–specific research, many of the strategies discussed here can also be used for teaching seniors about how to use e-books and e-readers and help move seniors more smoothly into the digital world.

REFERENCES

- United States Census Bureau, “ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates,” American FactFinder, accessed Apr. 17, 2013.

- Ruth Abbey and Sarah Hyde, “No Country for Older People? Age and the Digital Divide,” Journal of Information, Communication & Ethics in Society 7, no. 4 (2009): 226.

- Kathryn Zickuhr and Mary Madden, “Older Adults and Internet Use,” Pew Internet & American Life Project (June 2012), accessed Apr. 17, 2013.

- Ibid., 5.

- Ibid., 6.

- Zickuhr and Madden, “Older Adults and Internet Use.”

- Phil Turner, Susan Turner, and Guy Van De Walle, “How Older People Account for Their Experiences with Interactive Technology,” Behaviour & Information Technology 26, no. 4 (2007): 291-93.

- Dale Gietzelt, “Computer and Internet Use Among a Group of Sydney Seniors: a Pilot Study,” Australian Academic & Research Libraries 32, no. 2 (2001): 142.

- Emy Nelson Decker, “Baby Boomers and the United States Public Library System,” Library Hi Tech 28, no. 4 (2010): 614.

- Abbey and Hyde, “No Country for Older People?” 233.

- Ibid., 229.

- Ibid.

- Joan Ruthven, “Training Needs and Preferences of Adult Public Library Clients in the Use of Online Resources,” The Australian Library Journal 59, no. 3 (2010): 113.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Decker,”Baby Boomers and the United States Public Library System,” 612.

- Mary A. Cassell, Jo Ann M. Bamdas, and Valerie C. Bryan, “ReVisioning the Public Library as an Oasis of Learning,” International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology 3, no. 2 (2012): 13.

- Ibid., 16.

- Ibid.

- Turner, Turner and Van De Walle, “How Older People Account for Their Experiences with Interactive Technology,” 295.

- Cassell, Bamdas, and Bryan, “ReVisioning the Public Library as an Oasis of Learning,” 19.

Tags: senior programming