The Accidental Librarian – An Interview With Avi Steinberg

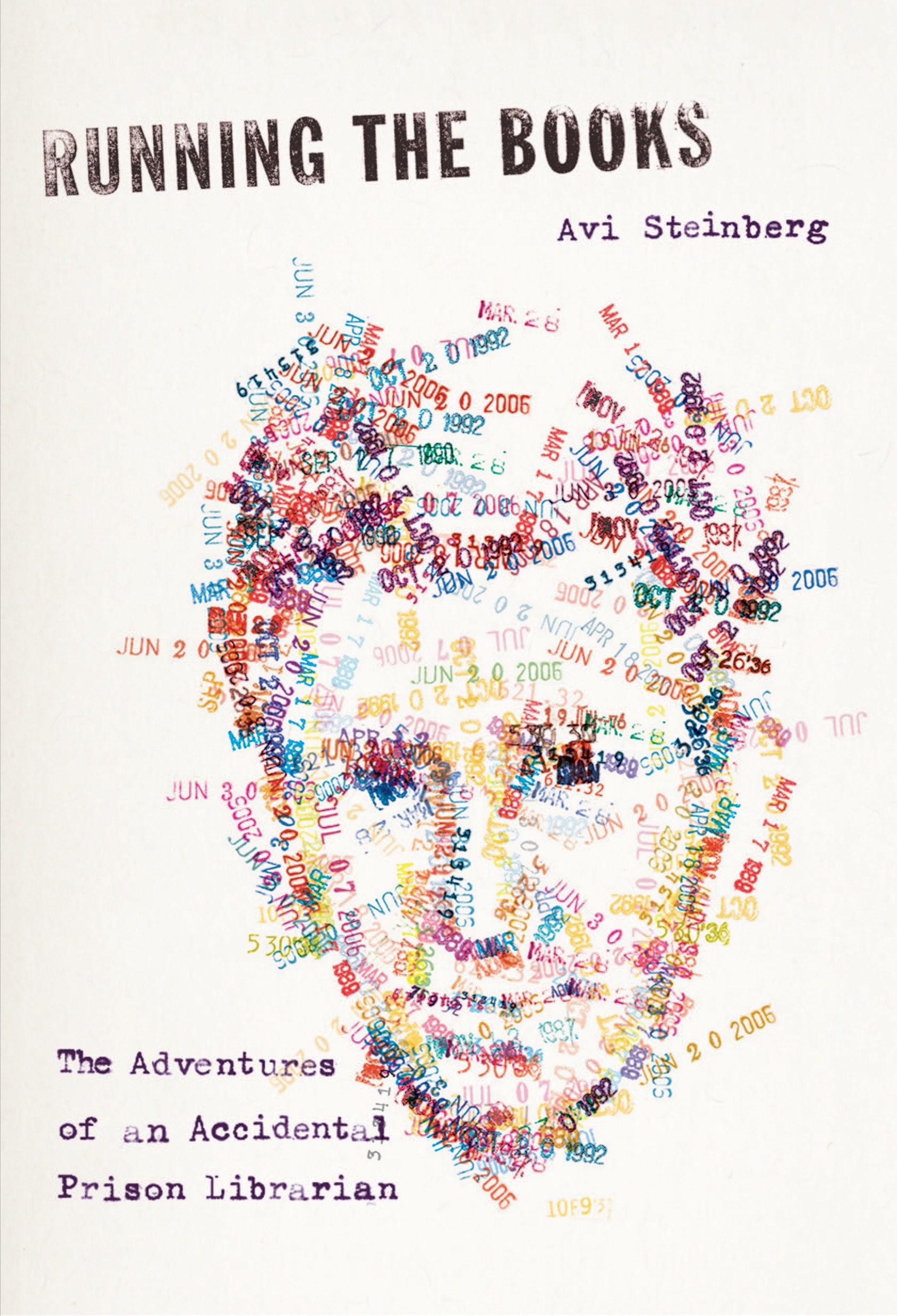

Avi Steinberg was a few years out of Harvard when he unexpectedly found himself working as a prison librarian in Boston. His account of his experiences, Running the Books: The Adventures of an Accidental Prison Librarian (Nan A. Talese, 2010), was recently hailed by The New York Times as “acidly hilarious.” Steinberg spoke to Brendan Dowling on October 28, 2010. More information can be found at www.avisteinberg.com.

Public Libraries: For people who haven’t yet read your book, how did you become a prison librarian?

Avi Steinberg: I was pretty fresh out of school and I was writing freelance obituaries and a couple of metro pieces in Boston. I just happened across an advertisement on Craigslist for this job, and I hadn’t even known this type of job existed. But I was very intrigued and I just kind of fell into it. As I say in the title, it was accidental, that really is true. I think I probably ended up there the way anyone ends up there, somewhat by accident.

PL: Can you talk about the role the library plays in prison, and how that differs from the role it plays on the outside?

AS: Well, some public libraries do serve the function I’m about to describe, but there was something about the library in the prison that really exemplified a community center. First of all, it physically was the center of this community. It was in a centrally located area where everyone would walk by, so almost every single person there would have some kind of contact with it. It ended up just being a place where people would go to hang out. So many people who came there didn’t come to read or to use any of the resources we were providing. They just came to see people. They came to see me, they came to see whoever was around. And it became a place where people would come to congregate for anything.

And I tried to harness this to encourage conversation. It wasn’t just a neutral slot, it basically became as I describe it—somewhat facetiously, but omewhat true also—a sort of pub where people come to check in. It was on everyone’s radar. Everyone shared it. It was like, “Yeah, I’ll see you at the library.”

PL: So everyone felt an ownership of it?

AS: I think so, obviously there were people who were regulars and really came every day and really used it. It was just a big part of the culture in a way. In the outside world some people go to libraries and some people don’t. There’s a very clear divide. Here it was just so prevalent that even people who didn’t really go knew about it and knew where it was, it was on their radar. There wasn’t much going on, so it sort of by default became this meeting spot. There are larger reasons why people are more interested in reading per se but as I try to emphasize in the book it’s not just about reading in this case. It’s actually just about sharing a space together.

PL: But why didn’t the prisoners choose some of the other shared spaces in prison, like the basketball court or the yard? Why the library?

AS: They do use those places obviously to some extent, but I think there’s something about the [library] space. It’s a very human-sized space. The yard is huge. It’s very easy to get swallowed up there because if you’re talking with someone you need to make a conscious effort to go spend time with that person. It’s much less social in a way. The library throws everyone together. It creates all these spaces where people are going to be standing next to each other naturally, leaning against the counter or sitting around the table. It’s designed to be social. So I think inevitably people are going to feel it’s a warmer space. The yard is not a warm place at all. Even the way it’s designed doesn’t allow for that.

PL: In your book you talk about how, in some ways, running a successful library in prison runs counter to the tenets of prison. How did you maintain a balance between those two forces?

AS: It’s a very tough question. For example, the use of Internet, which has become more and more central to the mission of public libraries outside, has a very circumscribed role in a prison. So basically anything that came from the Internet would come directly through me by way of printouts. So I sort of became, for better or worse, a guardian or gatekeeper of information, which is contrary in so many important ways to the idea of the library, that it has to go through some guy like me.

It’s inevitable in prison. Because if it weren’t there, there would be no connection at all to the Internet and to all the resources that exist online. And I tried to make that available to people—at least through me. But once again, that was a liberalization. I think there are some people in prison who think that’s even too much.

In terms of the rest of it, we tried to create a sense of responsibility. In a prison everything is a commodity, including books, of course. They have a value so they can get traded and we tried as much as possible to make people feel that these books are not a commodity. They’re something that belong to everyone and if you steal them you’re not stealing from the state, you’re not stealing from the government, you’re stealing from your fellow inmates. And that violates their code. You don’t do that. It’s okay to steal from the prison but to steal from your inmates is not okay.

We tried to create a sense of community and responsibility. That once again runs contrary to a prison, which is specifically not trying to create communities and not allowing people to lend to each other. So I guess the short answer is it was a delicate balance and sometimes we succeeded in making people feel responsible and defensive of the library and sometimes people took out their aggression about being in prison on the library. So it didn’t always work. It was certainly a case-by-case basis.

But I would say the instances of people abusing the library were the exception. I think the measures we took to make people feel more responsible ended up working for the most part: Getting to know people, putting a face on the library, being actively respectful of the people who came in. In other words not taking a neutral stance towards the people who came into the library, but actually being warm and welcoming. Making people feel that this place cares about them and respects them. And respect is very important in a prison and by that same token we demand respect as well. And I think actually in prison most people really respond to that, that’s taken very seriously. Because there isn’t much you can give in a prison, and so respect is something that can be freely given and people really respond to it.

PL: You also describe how the librarian you replaced had a much different attitude to his position. How did you differ from his approach?

AS: I poke fun a little bit at his hardline attitude, but I think I also try to acknowledge the fact that he ran a tight ship and in a prison that’s actually pretty important. To the extent that the place was pretty well organized and well run when I arrived was due to this guy. And it’s an understandable position. I think instead of saying he took a hard line, he took a stance of absolute neutrality. And he just said, “This is what we have to offer. Here are the rules, play by them or don’t and that’s it. And I’m going to judge you by how you follow the rules.”

Which is a fair position to take—I understand that. But I wanted to be a little more active. I wanted to go a little farther. I wanted to have rules and enforce them and all that but I also wanted to try to get to know people and create an environment of warmth, where people actually care about each other and have a sense of community. I’m sure he would look at that and say, “Look that’s a great idea, very nice, but that causes problems. And it’s asking to be abused.” And I can understand that.

Personally I think much more is gained even though some things are lost. I completely understand why someone—especially someone, to be completely frank, who’s planning on staying there for twenty years—would take that approach. But I wasn’t necessarily planning on staying there for that long. And I think maybe my approach wasn’t sustainable potentially. I have to admit maybe if I was going to be there for twenty years it would have been harder to pull off. But for the amount of time I was there it seemed like a reasonable approach.

PL: Working in a prison library has many specific challenges that don’t exist in the outside world, like “kites,” the notes prisoners hide for each other in the books. How did you deal with these challenges?

AS: When I came in there I felt like it was important to send a message that I was in control. I joke about that because obviously I went too far. (laughs) You try to do that, you start to look like you’re less in control. But it was important because as soon as I got liberal in there I saw things flip. It didn’t take much for things to get out of control.

I didn’t really care about people leaving notes to each other. I thought it was kind of interesting and completely understandable. I would do the same thing if I were in there. But the more I left those things in there it would have gotten absurd. There would have been notes falling out of every single book. I needed to send a message that I could stop it if I wanted to.

But as I describe I also felt guilty. I was messing with people’s mail, which is a crime. Not that it was actually a crime here but it still feels like a crime. When someone takes the time to write a long handwritten letter you don’t want to mess with it. So I found myself making these irrational compromises. For example I would remove a letter but I wouldn’t trash it, because I just couldn’t bring myself to throw it away. So it’s not actually helping anyone, but I felt like I was at least honoring the fact that the person had taken the time to write it by not throwing it in the garbage.

PL: And you ended up archiving a lot of them, right?

AS: I did, yeah. Probably because I was just—I don’t know what the impulse was. I felt like I needed to give them a place, whatever that place was.

PL: What happened to your archive of kites?

AS: I have it. I left some of it in the library. But basically I asked the other librarian if he wanted it and he said, “No, get that out of here.” (laughs) He was not into the idea at all. So I took it with me. I’m not sure what I’m going to do with them but I can’t throw them away.

PL: You also led a writing class as part of your job. You told your students that the goal of the class was solely going to be improving their writing skills, rather than the writing-as-therapy model to which they were accustomed. Why did you take this different tactic?

AS: It was somewhat of a tricky approach, because I do think writing’s therapeutic. But I didn’t want the class to be in the therapeutic model. A lot of these people have been through programs where writing was a component and writing is at the service of some very explicit therapeutic program. And I felt like that wasn’t really what writing is. It automatically biases the writing by forcing people to talk about how they’re getting better and how things are getting better. That’s not what people really want to write about.

So I wasn’t saying it wasn’t therapeutic, I was just saying the class wasn’t explicitly in the therapeutic model. I was like, “Work on the specific skills of writing— of describing detail and jogging your memory and challenging yourself to reflect on what had just happened.” And they’ll see there’s a subtle therapy that’s creeping in, there’s no question about it. It was based on my experience especially with the [female] inmates. All of them started writing the exact same essay. They’d done this a million times and thought they knew what I was asking them to do. I had to challenge them to do something else.

PL: So you changed your approach based on your experiences?

AS: I had one class with women and they were all like, “Oh yeah, I know what to do” and they would literally write the essay that they had already done a million times in these various programs. And it wasn’t useful. There was no point to it. I don’t know if it was ever useful but if it was it had already achieved its usefulness. And if we were going to do this writing class we were going to have to take it in a different direction.

Also it’s not the way I think about writing. I wouldn’t want them to do that. I can tell when people are not writing in their voice. Especially because I knew these people, I would spend time with them in the library. I knew how they talked and they weren’t writing remotely how they talked. I would read what they wrote and it didn’t sound at all like them.

PL: How did your background as a reporter influence the writing of your book?

AS: My impulse was to write more as a reporter, which as I slowly went through the process I dropped, partly because it’s not my personal style. So it took me a while to get there, I needed to write through it. But privileging other people’s stories to your own is what you do as a reporter and that’s something I’m still interested in.

PL: Is there anything you’re working on now?

AS: I have a couple of ideas but nothing specific yet, but definitely in that [reportorial] mode. I like to get out of myself and look around me. I’m not necessarily interested in myself and I don’t think anyone wants to hear it. (laughs) Maybe some people would, I don’t know. But it’s rarely the most interesting story at any given moment.

I think it’s good to own up to the fact that you’re in that situation, that you’re a participant in a given place. I think it’s just more honest. To pretend like you’re not there and from some Olympian height writing these things doesn’t make sense. It’s good to implicate yourself in the story. But putting yourself as the subject, I really think you need a good reason for that.

I certainly felt in this case I wasn’t the main subject. None of us really were. I think the library itself was. It was really about the place more than people and it got at the place by way of the people. And I was one of those people, but only one.

PL: What have your former coworker’s reaction to the book been?

AS: Certain people on the staff have definitely read the book. My former boss said she liked the book. I think she was somewhat creeped out by the whole process. She actually had a very reasonable take on the whole thing. She said, “Obviously I’m going to read the book and immediately gravitate towards the parts that we’re mentioned in, but I also know that’s not what this book is about. It’s not just about us.” I thought that was a very reasonable take on things.

[It’s tough] because they’re still there. They’re still in the trenches there. So it probably has compromised them to some extent, and I do feel bad about that. I also think at the same time [the book’s] given credence to some of the work they do. It’s articulated some of the things they go through and given credit to their work. I also hope they can take it as I wrote it, which is lovingly and honestly and as one of them, to some extent.

PL: What about the prisoners you write about? Are you still in touch with them? What has their reaction been?

AS: Some of them I’m in touch with and the ones who I’m in touch with obviously know. The other ones, not. And I would like to be in touch with them. There are some who I’m actually looking for but it’s not always easy to stay in touch with people who’ve gotten out of prison. People kind of disappear. They often just want to leave it behind them. It’s kind of hard in some cases to find people and there are certain people, I want them to see this.

Too Sweet, the pimp [I write about], he I’m in touch with, and I feel like he’s in some ways the one I’m most critical of. And he’s okay with that because he’s pretty critical of himself actually. We’ve had a pretty open and honest conversation about these things. The rest of these people, I definitely tell their stories but I do feel there’s a good deal of privacy there. The two people who I go into their lives the most are dead. So that’s obviously a slightly different situation. Chudney’s family I actually am in touch with and I visited them. They know that I wrote this thing and they’re actually very grateful for it because they see it as a memorial to their son.

PL: In some ways, his dream gets realized through the publishing of the book.

AS: I feel that way. I mention in the book that he didn’t get an obituary [when he died] and my first impulse was, “He should get an obituary.” So I hope this book is something like that for him.

Tags: prison libraries