Learning from Librarians and Teens about YA Library Spaces

Young adult (YA) librarianship has received growing attention in the library literature over the past several years. However, the majority of writing on this topic has focused on the services provided rather than on the physical spaces where these services take place. As U.S. public libraries are evolving to meet users’ changing needs, we are in need of new design principles that reflect how users are actually using and interacting with their library spaces.1 Physical design elements have a large impact on how welcoming and comfortable the library feels, making user-centered design a crucial consideration in serving teens.2

Most of the limited writing about public library spaces for teens is based on informal case studies or anecdotal evidence rather than data-driven research.3 In 2010, in recognition of the need for more formal research into YA library space design, the Institute of Museum and Library Services awarded San Jose State University a three-year research grant to conduct the first large-scale empirical study of the physical and spatial aspects of YA library services.

One component of the grant involved gathering video data from YA librarians and teen library users (ages twelve to eighteen). The libraries that took part in the study were selected from a group of U.S. public libraries that had renovated their YA sections between 2005 and 2010. At each of the twenty-two participating libraries, the YA librarian agreed to record a two- to three-minute video tour of the library YA space and to invite a teen library user to record an additional video tour of his/her own. Participating librarians and teens were asked to create video tours of their library spaces as they wished to show them. They were not asked to focus on any particular areas of space or design. In all, twenty-two librarians and twenty teens created videos. Together these forty-two videos can provide us with insight into the thoughts, feelings, and needs of teen library users and of the librarians who work in these spaces.

It is important to note that a majority of the existing professional and research literature dealing with YA library services has been written from adult librarians’ and researchers’ perspectives, assuming that adults know the “best” approaches to YA services design and delivery.4 Our study sought to gather data from both teens and their librarians, thereby giving teens and adults equal voice in the examination of YA space design. In analyzing the videos, we compared the librarians’ and teens’ responses, both in terms of themes identified within the videos and in terms of the frequency of occurrence of each theme. When compared, librarians and teens agreed on some aspects of their new or recently renovated spaces while demonstrating some disagreements as well. In the sections that follow, we discuss the results of the video analysis in detail and explain what these results mean for best practices in public library services to teens.

Frequently Mentioned Themes

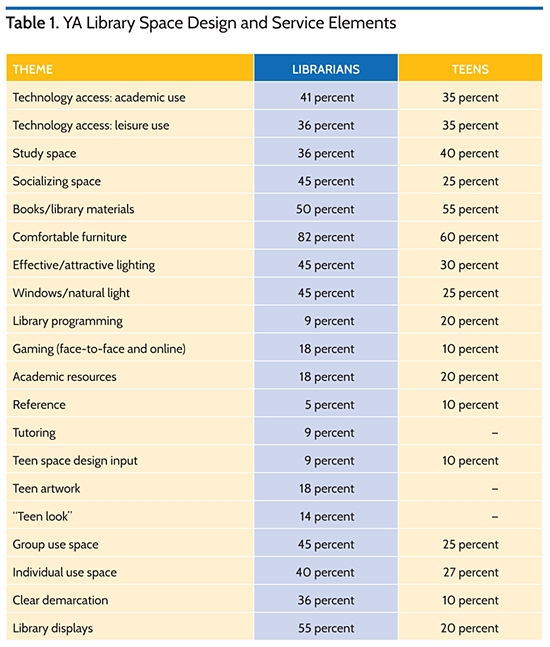

The full list of themes that resulted from analysis of the videos appears in table 1. Some of the themes appeared in a relatively large percentage of the videos, whereas other themes appeared less frequently. Themes that both librarians and teens mentioned frequently included the importance of access to technology; study and leisure spaces; leisure reading and media resources; and appealing furniture and lighting.

Access to Technology

Access to technology was one of the most frequently and enthusiastically mentioned themes, with a majority of the study participants identifying computer access as a major function of their YA library spaces. Forty-one percent of librarians and 35 percent of teens made comments regarding computers for academic use, such as writing research papers or completing other homework projects. Thirty-six percent of librarians and 35 percent of teens discussed library computer use for leisure activities, such as social networking.

It was evident in several of the videos that flexibility and mobility in computer use space design can enhance this blended usage of library technology for both academic and leisure use. As one librarian explained in her video, “We have eight computers total. Right now they’re all desktop computers, but we’re hoping in the near future to get laptop computers to offer us more flexibility with the space.”

Study and Leisure Spaces

In addition to technology access, librarians and teens also frequently discussed using YA library spaces for more general academic and leisure pursuits. Thirty-six percent of librarians and 40 percent of teens mentioned the importance of providing study spaces for teen library users, while spaces for socializing were mentioned by 45 percent of librarians and 25 percent of teens. Both librarians and teens indicated that spaces designed with flexibility for supporting multiple functions were more effective than separate spaces dedicated to either academic or leisure use.

For example, one librarian stated, “These study rooms can be used to study, for tutoring, or just to hang out with your friends, so they’re used almost every day. There [are] usually groups in each of them, whether it’s tutors or kids hanging out.” Similarly, a teen commented that, “Usually when people are in here they’re studying, they’re socializing, they’re having fun, and they’re just having a good time in here.” Even individual study rooms were sometimes used for group leisure activities.

Leisure Reading and Media Resources

As national surveys have shown for the past several years, within the U.S. population the most common perception of libraries continues to be the traditional image of libraries as book providers.5 This strong focus on books was echoed in the videos, with half of the librarians (50 percent) and a little more than half of the teens (55 percent) discussing books and other library resources in their video tours. Books, especially fiction, generated enthusiastic comments from several of the teens, and both librarians and teens stressed the current popularity of manga collections and other popular genre collections.

In addition to books, other library resources such as magazines and music also received attention, showing the importance of varied collections to meet teens’ varied tastes. As one teen stated, “Over here we have the graphic novels—very, very, very popular among the young people. Over here are the magazines and the CDs. With the CDs, there’s a wide range of genres. It ranges from rock to hip-hop to country, and just all the stuff young people like to listen to.”

Appealing Furniture and Lighting

Both librarians and teens emphasized the importance of comfort, flexibility, and fun in furniture and lighting. Eighty-two percent of librarians and 60 percent of teens discussed the importance of comfortable furniture in their teen spaces. Forty-five percent of librarians and 30 percent of teens discussed the importance of effective, attractive lighting. Librarians were more likely than teens to emphasize windows as important design considerations, with 45 percent of librarians and 25 percent of teens discussing a preference for windows that could bring plentiful natural light into the spaces.

Teens described furniture from the users’ perspective, while librarians tended to take an observers’ perspective, highlighting an advantage of soliciting teen input when studying YA library space design. Video commentary from both librarians and teens makes it clear that furniture and lighting directly influence teen users’ experience of the library and their desire to use the materials and services provided in YA spaces. For example, this quote from a librarian shows how unappealing lighting can have a negative impact on the use of the space: “We’ve got that track lighting, which we can’t have all of them on because [then] it looks like an interrogation room in here.”

Less Frequently Mentioned Themes

Themes that both librarians and teens mentioned less frequently in their videos included the importance of programming and gaming space; academic resources, reference services, and tutoring; and creating a teen atmosphere. Even though fewer study participants chose to discuss these themes, they still offer insight into some of the important aspects of YA space design and suggest ideas for making library spaces more appealing to teens.

Programming and Gaming Space

Within the professional literature, library programs and gaming are commonly accepted as popular library activities for teens, yet programming and gaming received less attention than some of the other reasons for teen library use. Just 9 percent of librarians and 20 percent of teens discussed library programming in their videos. Eighteen percent of librarians and 10 percent of teens commented on gaming in the library, including both face-to-face and online gaming. However, providing gaming opportunities in the library might lead teens to explore other available library programs and services. For example, one of the teens explained, “These different gaming systems really do bring in a lot of kids, and many times, as they go through [the library] they end up taking a look at the computers, the laptops, the fun treats that you can win by knowing the five vocabulary words.”

Academic Resources, Reference Services, and Tutoring

While more than a third of librarians and teens identified study spaces and academic computer resources as important aspects of their YA spaces, other materials and services addressing teens’ academic needs received less attention from both groups. About one-fifth of librarians (18 percent) and teens (20 percent) discussed physical materials to support academic needs, including college preparation and curriculum support materials. It is possible that insufficient marketing is at least partly to blame. As one teen suggested about the college preparation material: “A lot of kids either don’t know it’s here or don’t really feel comfortable coming in to use this stuff.”

Reference services, which have long been a major focus of public library services, were even less frequently mentioned than academic resources. Just 5 percent of librarians and 10 percent of teens discussed reference. Teens were more likely to mention positive social interactions with librarians than any kind of reference work. Tutoring, likewise, received mention from only 10 percent of librarians and, again, none of the teens.

Creating a Teen Atmosphere

A common theme in the YA library spaces literature has been the importance of creating a “teen atmosphere” and including teen input in YA library space design. It is suggested that these efforts will result in spaces likely to appeal to teens and to give them a sense of ownership of their library spaces.6 Considering that examples of public spaces that teens can call their own are rare in other sectors of society, it seems that public libraries could be an important place for fostering feelings of teen ownership.7 However, just 9 percent of librarians and 10 percent of teens mentioned including teen input in space design. Eighteen percent of librarians but none of the teens mentioned using artwork created by teens to decorate teen spaces as a method of promoting teen ownership of their library spaces, and just 14 percent of librarians (and none of the teens) emphasized the importance of creating a “teen look.” Librarians might talk to teens for ideas about additional ways to promote the feeling of YA space ownership among their teen communities.

Variance among Librarians and Teens

A few themes received different levels of responses from librarians and teens and revealed possible disagreement about the preferred uses and design of YA library spaces. These themes included group and individual space use; demarcation from other library areas; and library displays.

Group and Individual Space Use

There was a noticeable difference between the frequency of librarian and teen responses regarding spaces designed for group and individual use. Although nearly half (45 percent) of librarians made comments about the need for spaces where groups of teens could socialize and hang out in groups, just one-fourth (25 percent) of teens discussed using library spaces for group socializing. In contrast, 40 percent of teens mentioned a desire for lounging spaces designed for individual use and spaces designed for private study or reading, while only 27 percent of librarians identified this need for individual-use spaces.

The teens’ less frequent mention of the desire for library spaces to socialize is surprising, as previous literature has shown the opposite.8 In this study, however, teens expressed more desire for personal space and privacy in the library than for spaces that could support group social use. For example, one teen said, “I really like the comfy chairs in front of the flat screen, but I wish they were spread out more so you don’t feel on top of the other reader. I don’t always sit down at them if I’m going to be right next to the person in the next chair.” As a result, this study shows that balance between spaces for private individual use and for social group use is likely to appeal to the greatest numbers of teens, and that adults must be careful not to characterize teens as wanting constant social interaction.

Demarcation from Other Library Areas

Interestingly, slightly over one-third of the librarians (36 percent) emphasized the need for a clear demarcation of YA spaces from other parts of the library, whereas only 10 percent of the teens expressed a desire for visual or physical separation from adult and children’s library spaces. The teens who did discuss the separation of the YA section from the rest of the library explained that it made them feel more welcome in the YA spaces and that it improved the overall YA space atmosphere. For example, one teen said that: “Having the teen section on the third floor is really great because . . . the younger kids don’t make the trip up to the third floor . . . so we don’t have little kids running around, and it’s quieter.” Although it might not be possible physically to separate the YA space from the rest of the library, librarians can use bookshelves and pieces of furniture to create visual separations, or use different decor to achieve the same effect.

Library Displays

More than half (55 percent) of the librarians and just one-fifth (20 percent) of the teens discussed library displays (book displays, information boards, library policy postings, and signage) in their videos. It is perhaps unsurprising that librarians were more likely to discuss library displays since they are typically in charge of creating them. Still, this striking pattern of responses raises some significant questions, such as whether teens would place greater value on policies and displays if they had greater involvement with their content and creation. It could even be questioned how necessary or effective displays and policies are to begin with since so few teens mentioned them in their video tours.

Conclusion

The study of YA library space design is relatively new, and it lacks a foundation of evidence-based research. Accordingly, this study was exploratory in nature and the ideas presented here are preliminary. The explanations offered in this article need to be examined in more depth through deeper study, such as follow-up interviews, focus groups, and other conversations with librarians and teens.

However, some clear conclusions can be made from this study. First, as the public library’s role continues to shift in the modern information environment there is a need to focus on what happens in library spaces—not just what is contained in those spaces. While the librarians in this study often concentrated on discussing library materials and resources, the teens tended to emphasize their actions and experiences during library visits, indicating that they appreciate their libraries not just for the resources that they offer but also for the activities and experiences that take place there. To create spaces that can best support the changing needs of contemporary teens, it is beneficial to view YA spaces from an expanded perspective of the functions and interactions taking place within them rather than strictly evaluating the materials and services they provide.

Next, this study has shown that teens’ opinions about a space do not always match librarians’ perceptions. Librarians must perform periodic teen needs assessments to determine the specific needs and preferences of their user communities, rather than trying to guess what those needs and preferences might be. In all YA space design decisions, local teen voices should receive the highest possible respect and value. Teens may not always be highly vocal in expressing their opinions or understand what kind of feedback would be most helpful, and librarians have more experience evaluating their spaces and a greater vocabulary for describing them, making it easy to hear their voices the loudest. This means librarians must actively solicit teen input and provide environments supportive of meaningful evaluation activities. Above all, it is essential to remember that YA library spaces are intended to benefit teens in the ways they choose to interact with and within them.

Finally, both librarians and teens need to be properly prepared to make informed contributions to assessment. Both groups may not be fully aware of what to expect from public spaces in general or the full range of possible improvements their library could provide. In the future it could be useful to develop tools to help those involved give meaningful feedback and empower the voices of teens and all stakeholders in YA spaces to engage in designing library spaces that comfortably and effectively meet their own needs.

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank Jeremy Kemp, Mike Males, Mara Cabrera, Lori Harris, Yvette Khalafian, and Zemirah Lee for their comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this article.

References

- To learn about how some public libraries are evolving to meet users’ needs, see Tom Mullaney, “Libraries Reinvent Themselves for the 21st Century,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 12, 2013, accessed May 22, 2014.

- Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA), National Teen Space Guidelines (Chicago: ALA, 2012), accessed May 22, 2014; Anthony Bernier and Mike Males, “YA Spaces and the End of Postural Tyranny,” Public Libraries 53, no. 4 (July/Aug. 2014).

- Anthony Bernier, Mike Males, and Collin Rickman, “‘It Is Silly to Hide Your Most Active Patrons’: Exploring User Participation of Library Space Design for Young Adults in the United States,” The Library Quarterly 84, no. 2 (Apr. 2014).

- Denise E. Agosto, “Envisaging Young Adult Librarianship from a Teen-Centered Perspective,” in Transforming Young Adult Services, Anthony Bernier, ed. (Chicago: ALA Neal-Schuman, 2013): 33-52.

- Cathy De Rosa et al., Perceptions of Libraries, 2010: Context and Community—A Report to the OCLC Membership (Dublin, Ohio: OCLC, 2011).

- For example, see Ann Curry and Ursula Schwaiger, “The Balance Between Anarchy and Control: Planning Library Space for Teenagers,” School Libraries in Canada 19, no. 1 (1999): 9-12; and Kimberly B. Taney, Teen Spaces: The Step-by-Step Library Makeover, second ed. (Chicago: ALA Editions, 2009).

- Patsy Eubanks Owens, “No Teens Allowed: The Exclusion of Adolescents from Public Spaces,” Landscape Journal 21, no. 1 (Mar. 2002): 156-63.

- Vivian Howard, “What Do Young Teens Think about the Public Library?” The Library Quarterly 81, no. 3 (July 2011): 321-44.

Tags: YA Library Spaces