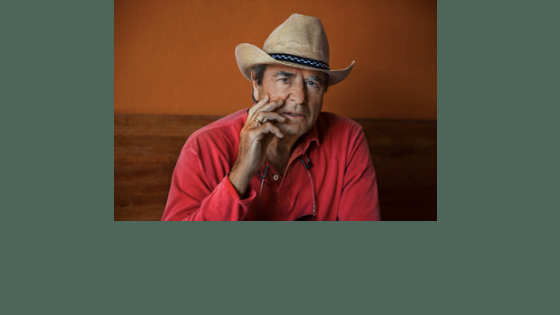

“The World Looks More Fragile Than It Did When I Was Younger”—A Conversation with Paul Theroux

For over fifty years, Paul Theroux has set the gold standard for travel writing. Now in his seventies, he remains as curious and fearless as ever, as evidenced in his new book, On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey. The book is an extraordinary chronicle of a hugely ambitious trip Theroux undertook, where he drove the entire length of the US-Mexican border, and then deeper into Oaxaca and Chiapas. Along the way, Theroux spends time with Zapotec mill workers, attends a Zapatista party meeting, and teaches a creative writing class in Mexico City. Through it all, Theroux lends his formidable powers of observation to these areas of Mexico rarely visited by its northern neighbors. The Washington Post raved, “Theroux extracts such life-affirming joy from the road that you hope it keeps unfurling before him,” while The Boston Globe said, “On the Plain of Snakes couldn’t be more vital, informed, inquiring or big-hearted.” Brendan Dowling spoke to Paul Theroux via telephone on September 24th, 2019.

What inspired you to tackle this project of traveling the Mexican border?

I would say that first, curiosity. When I saw the border for the first time I thought, “I’ve never seen anything like it.” I had never seen anything so dramatic. which was to be in Nogales, Arizona and see this big metal wall, walk through the door, and suddenly be in another country—just through a turnstile. The drama of that was like Alice down a rabbit hole. The other thing was Trump disparaging Mexicans and stereotyping them. I thought one of the reasons for writing about travel is to destroy the stereotypes, to see people for who they are in all their humanity and subtlety.

What were your family and friends’ reactions to this project?

You know, I’ve been traveling my whole life. I first broke it to my parents in 1963 that I was going to Africa for two years. This was a time with no cell phones. “I’ll write you a letter!” (laughs) Now, fifty-six years later, I’m doing the same thing. I just assume that people will accept that I’m a curious, restless person and it’s part of the job. My wife was very supportive of the trip, as she always has been. People were saying, “Don’t drive. Be careful.” All the things that cautious people would say. When people say, “Be careful,” of course I’m going to be careful! You have to assume that luck is on your side. You have to take precautions, which I did, and do the best you can, but you can’t listen to people. If a Mexican had said, “Don’t do it,” I probably would have abandoned the whole thing, but it was only people who hadn’t driven to Mexico.

You wrote about crossing the Mexican border in The Old Patagonian Express in 1979. What was different in your border crossings nearly forty years later?

Big differences. For one thing, in 1978 and 1979 when I first went across the border, the border was very stable. People went across all the time—as they do now—but there was no paranoia about coming or going. The border was much more casual, much more informal than it is now. Now it’s very rigid. I suppose the paranoia people have now is because so few people go across the border to have a good time. The border towns on the Mexican side have shriveled up in terms of entertainment, but they’re much more industrial, there’s much more manufacturing, They’re more thickly settled. They’re denser. They’re more business like. I should also say, though, that they’re also more dangerous.

What’s caused those changes?

The changes that have come are just the way the world has changed, which is there are more people in the world, there are more poor people in the world, and there are more people looking for work. All borders in general are getting tighter. I think Mexico developed in a different way. We began to see Mexico as a potential manufacturer, so a lot of people outsourced their manufacturing to Mexico that had not done it before. My previous travel book was called Deep South. When I was in Arkansas I went to a lot of places that made shoes, electronic television sets, radios, and whatnot, and I’d say, “What happened to your manufacturing?” And they always said, “It went to Mexico.” The story of American manufacturing is that a lot of it disappeared and went elsewhere—to Viet Nam, China, India, and off to Mexico. So the border is culturally different, it’s socially different. Commercially it’s a different place. It’s not funky cantinas and mariachi bands, it’s people working. They never stop. A lot of these manufacturing jobs have three shifts, and they work all day. It’s twenty-four seven manufacturing.

Some of them are only a hundred yards from the border. They work, make whatever they make, put it on a truck, truck it over the border, and come back in. It’s not like manufacturing is in the interior of Mexico—although there are a lot car plants, Chevies are made deeper in Mexico—but the border makes a lot of goods, big and small, and they just truck it that short distance. The reason why people make stuff in other countries is because workers are not unionized and they work for less money. Businesses are looking for cheap labor, and there’s plenty in Mexico.

You talk about your philosophy of visiting a country is “Stay longer, travel deeper.” Can you talk about what you’ve learned by doing so?

I think that the best thing that I ever did in my life was become a Peace Corps volunteer. I’ve been publishing books for over fifty years and I’ve published quite a few books. My attitude has always been rather than just skate on the surface, to go some place—ideally you work in a place, work with other people as partners and find out what their lives are like. Philosophically I’m much more attuned to the idea of living in a place, working in a place. In Mexico I was a teacher for a period and I was a student for a period. In other places I’ve been just a wanderer, I have to admit to that, just going from place to place as a traveler. As I’ve gotten older, I spend more time with people that I’ve traveled among; I take them more seriously. When I was younger I was sort of flippant. I saw travel in a very self-centered kind of way; I didn’t look too deeply into it. Ideally we spend more time in the place that we’re traveling in, get to know the people better, and speak the language.

I also discovered rather than wait for a bus or a train, driving is the perfect way of traveling. I have more freedom to travel if I have my own car. That was a revelation that happened when I was traveling in Africa writing The Last Train to Zona Verde. That was in 2007. After that I thought, “I’m going to travel in the States and I’m going to drive.” I drove around the south and I used the same method of driving across the border. It ended up being an amazing experience and also a very liberating way to travel. You wake up in the morning, get in your car, and go. You can stop anywhere you like. You’re somewhat vulnerable to cops or anyone who wants to take your car. I was traveling alone, but I still thought, “That’s my way of traveling.”

Over the years I’ve changed. My method of travel has changed. My attitude has changed. I’m an older traveler now and I see things slightly differently. I’m way past retirement age, but I’m still doing it. The world looks different to me now than it did when I was younger.

Can you talk about how your attitude toward travel has changed?

It’s changed because I’ve gotten older and, I think, more serious. The world looks more fragile than it did when I was younger. The world looked very big, complicated, and exotic to me when I set off in 1963 to go to Africa. I felt I was traveling into the unknown. Now it’s less and less unknown. Very distant places are more familiar. They’re linked to us. You go into a supermarket and there might be an Indian behind the counter and a Nigerian migrant buying something. They’re not distant people anymore; they’re our neighbors. The world has come to our shores. The developing world has set its sights to a large degree on finding some kind of economic salvation in the States. So I’m not going to a place that’s isolated. There are very few places in the world that are isolated. That changes your view. You suddenly see that most places in the world are accessible.

The Internet has changed a lot, so people are connected in a way they never were before. They’re also poorer than they were. I think the difference between the poorer parts of the world and the wealthy parts of the world are much greater. The disparities of incomes are much greater. All of these are factors you have to take into account. I’m less interested in sightseeing, but I was never interested in sightseeing to tell you the truth.

You thread works of literature set in Mexico and by Mexican writers throughout your book. What role have these books played in your understanding Mexico? How did you decide to include them in the book?

I wanted to understand Mexico through its writers, because writers have a particular vision of their country. What I found are Mexican writers are brilliant. They’re not translated into English, or very few of them are. They have a very keen eye for what’s happening in Mexico. They tend to write about the urban areas—they write about Monterey, they write about Mexico City, they write about Pueblo—but they don’t write about rural places. They tend to be urban or urbane writers. I thought, “What do you understand about Mexico by reading, particularly fiction and poetry?” You understand a lot, but you don’t understand everything, because there’s spaces where those writers don’t go. I wanted to familiarize myself with that writing. Mexican writing is an old tradition and a lot of it’s unknown in the states.

I also like talking to writers. In The Old Patagonia Express, I met Borges in Argentina. When I wrote about Africa, I met Naguib Mahfouz and Nadine Gordimer. In Turkey I met a man called Yaşar Kemal. I’ve always sought out writers because we have a common destiny. They tend to be observant and articulate. Spending time with writers for me is a lot of fun. All creative people are fun to talk to; they tend to be outward looking, they tend to look at what’s happening in the country. One of the most observant was a man called Francisco Toledo, a painter. I met him in Oaxaca, spent some time with him, and wrote about him. There’s a chapter about him. He died about three weeks ago I regret to say. He was a wonderful guy. Painters look very carefully at a place. That’s helpful to talk to people who are looking at the place they’re living in, the country they’re living in, at other people. They’re out and about. They’re concerned about what they see. The same is true with the writing. Creative people tend to be more alive, more alert, and it’s helpful if you’re writing about a place to connect with them and talk to them.

What advice would you have to people traveling to Mexico?

First I would say try to see the Mexico that’s away from the beach resort. I would also say look at Mexico’s history. Notice, for example, that Mexico used to be California, Nevada, Arizona, and Texas. A lot of what is now the United States was once Mexico. Be sensitive to the history of our intimidation of Mexico. You’ve got to tread carefully, because you can’t assume that we haven’t had a gigantic impact on them. I would say learn Spanish. Try to talk to people. Take your time. All travelers need to be patient. They need to be humble. They need to be listeners. They need to be well informed. I would say before you go to Mexico read about it. If you know a little bit more about where you’re going, you’re likely to come back with more information, more enlightenment.

And finally, what role has the public library played on your life?

A gigantic amount. I can say I did not go into a bookstore and buy a book until I was about twenty years old. All the books that I had were from the local library. I was born in Medford, Massachusetts, and the library was an old mansion on the main street of Medford called the Methune Mansion. It was nice and old and had comfortable chairs. I can say I spent my early youth in libraries. One thing you get from a library—particularly when you’re able to roam from shelf to shelf—is you discover books. You’re looking for a particular author, and then you see a book next to it, and a book next to that, and it’s yours.

All the great intellectual discoveries up until the time I graduated from college were in libraries. To me it was probably the most significant intellectual resource I had. There was a local library near where I lived in Medford, and then we had the main library. I used them all the time.Books were expensive. Even when I was growing up. I would think, “Why would you buy a book, because you’re only going to read it and put it on a shelf?” My notion was always you get books from the library, read the book, bring it back, and then get another book.

This idea of the connection between the reader and the writer, I felt very strongly. From a very early age, I idolized writers. I actually felt writers were magic. They were unapproachable. I had a very elevated notion of what a writer was like. I saw them as very heroic figures. I also saw them as outlaws, that they were people breaking the rules. When I was growing up in the forties and fifties, some books were banned. It was also this idea that I had that there were some books, some authors, that were unobtainable. DH Lawrence, Henry Miller, to name a few. It wasn’t really until the 1960s when Lady Chatterly was available. Before then, they were outlaw figures. They were dangerous people. Books had that sense of danger and rebelliousness in them. They were in the library. I can say that the library to me was an escape and a tremendous resource. I found everything in a library that I couldn’t find at home, including the comfort to sit in a chair and read uninterruptedly.

Tags: Paul Theroux