Library Staff In and Beyond the Workplace

This is the final installment in the series about the impact of COVID-19 on library staff, based on results from PLA’s February 2021 survey of the public library field. In analyzing those results, my focus has been on workplace policies and practices that can better support staff and make libraries more welcoming spaces for staff and patrons alike.

Part 1 in the series addressed the challenges staff face – including burnout – and the particular health and safety concerns of the pandemic. To help libraries provide better support, Part 2 focused on how remote work in libraries has changed over the past year, and what it might look like in the future. This final installment focuses on how and why library policies can better serve people who are caregivers and why it matters.

Caregiving and Pandemic Challenges

Caregiving comes in many forms, including parenting, childcare, elder care, or looking after a sick partner or other relative. Caregivers can be parents, grandparents, relatives, or neighbors. On PLA’s survey, 9 percent of respondents felt access to family or sick leave at their library was inadequate, while 49 percent said it was exceptional. Accommodations for caregivers were rated inadequate by 14 percent of respondents, and exceptional by 30 percent.

The survey comments indicated that inadequate support has two main characteristics: lack of access to paid leave and caregiver accommodations, and lack of flexibility, especially for part-time staff. A lack of support can have serious consequences for individual staff members, libraries, and the profession as a whole. It is a particularly pressing issue within the library profession as it is predominantly female, and women are more likely to be caregivers.

During the pandemic, parenting and care-giving responsibilities have disproportionately impacted women, and nonwhite single mothers have been hardest hit. Leaving the workforce even temporarily has negative impacts on individuals’ careers and financial status. One survey respondent wrote, “I had to take a cut in my hours because I was not able to find childcare for my children and my library was not supportive of me working from home during off hours.” This is not only an issue for parents. A respondent shared, “I’m a caregiver and I would love to be able to work partially remote and partially in office. A colleague with a child can do that, but I can’t because I’m caring for an elder instead of a child.”

Supporting Caregivers

When libraries implement good policies that accommodate caregivers’ needs and provide flexibility, that makes a positive difference for staff. Amandeep Virk, Library Assistant at Chandler Public Library in Arizona, shared that early in the pandemic she was able to use vacation time to supervise her young daughter’s remote schooling. Later, she worked remotely on some days and her husband looked after their daughter on days when she had to be in the library. She reflects that this flexibility and the “safety measures and policies made a huge difference in my personal life,” and she feels “supported and important at the same time.”

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) enabled employees to take paid leave if they became ill with COVID-19, if they needed to quarantine, or to care for a child whose school or daycare closed. However, the rules expired on December 31, 2020 and not all employers maintained the same policies, despite the continuation of the pandemic. The Cleveland Heights-University Heights Public Library in Ohio did opt to continue to offer leave to employees through June 1, 2021. Kim DeNero-Ackroyd, Deputy Director, had several staff members take leaves of absence to care for children, and she says, “having the ability to alter a schedule was very important” for them. The library’s updated leave policies offer all employees paid sick leave under the same terms as the FFCRA. The policies also offer any employees who have worked at the library for more than 6 months the option to take a leave of absence for childcare and the option to request schedule adjustments because of childcare.

Where implemented, FFCRA policies made a difference: research suggests that increasing access to sick leave reduced the number of COVID cases. The pandemic will (hopefully) end and some of the associated pressures will relent as children go back to schools and daycares and vaccinations reduce the threat of illness. Yet even pre-pandemic, a survey found that 60 percent of working adults anticipated needing to take leave for elder care and/or parenting in future. The “sandwich generation” may have to provide both types of care at the same time. The pandemic has heightened awareness of caregiving needs and stresses, but the issue is not new, nor will it go away.

Why It Matters

The United States is unique among advanced economies in not guaranteeing paid family or medical leave, instead leaving it to employers to offer those benefits voluntarily. Unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leaves many workers in a position of choosing between their health and being able to pay their bills.

Libraries cannot fix this issue on their own. Nonetheless, there are things libraries can do to address inequities and better support their workers. ALA’s Committee on the Status of Women in Librarianship (COSWL) presented a free webinar in February 2021 on “How Employers Can Support Library Workers Who Are Caregivers During COVID-19.” The presenters emphasized that policies that benefit caregivers benefit everyone because they create a more welcoming and supportive environment. (COSWL has also compiled a Caregiver’s Toolkit with links to many resources.) The best policies include flexibility, autonomy, sick leave, clear communication and expectations, and a culture of transparency.

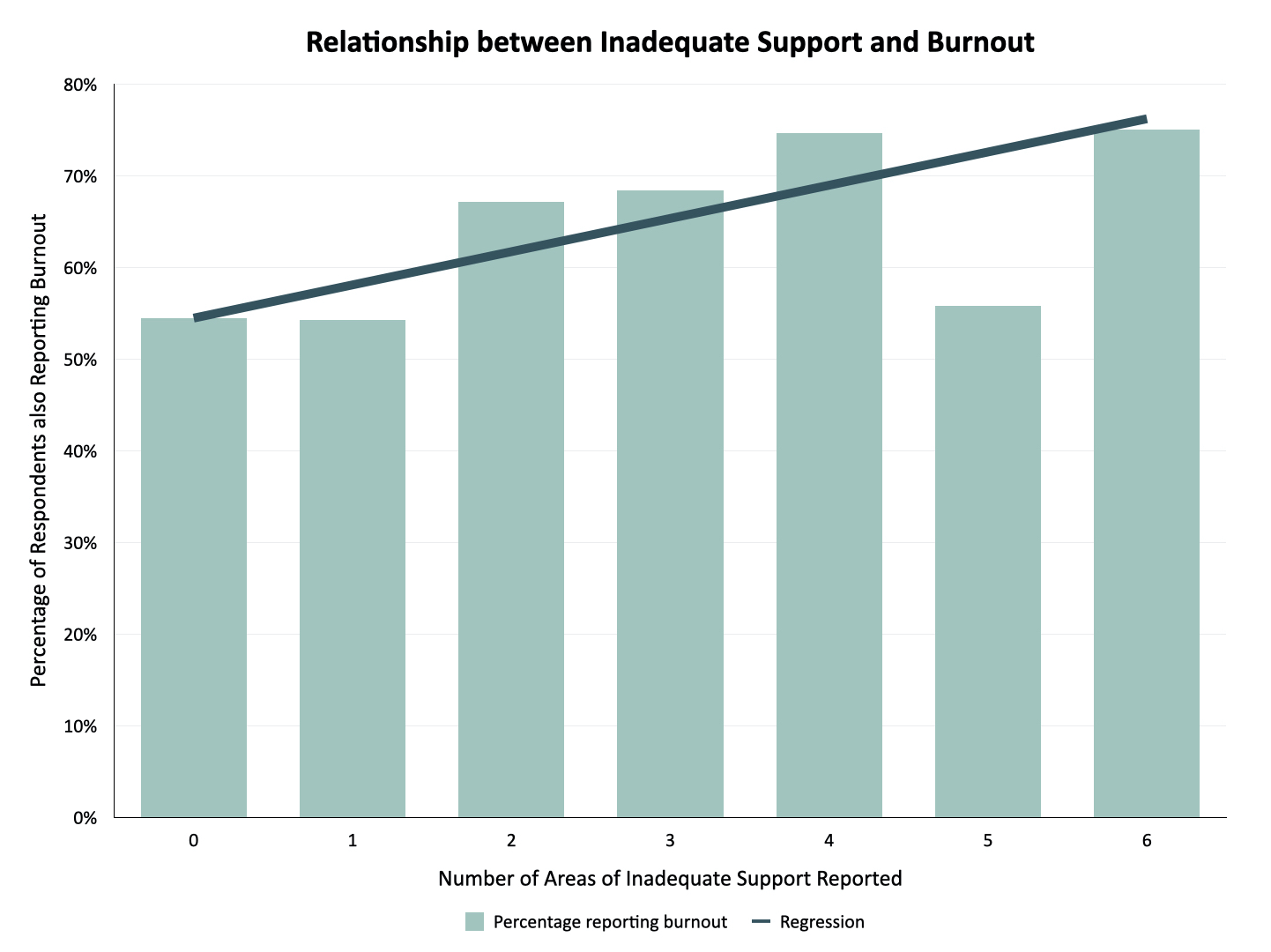

Not supporting staff has very real consequences. Further analysis of the relationship between staff support and burnout (discussed in part 1) shows that there is a statistically significant correlation (p<0.01) between the level of support library staff feel they have received and whether they reported experiencing burnout during the pandemic. Respondents who reported lower levels of support overall were more likely to report burnout (among the 2,179 respondents who answered both relevant survey questions).

Another way of looking at this is shown in the chart below. There were six key areas in which respondents evaluated the level of support they felt their library has provided during the pandemic. The chart shows the total number of areas out of six where respondents felt their library provided inadequate support, and the percentage of those respondents who reported burnout. The slope of the line is positive and statistically significant (p<0.01). This means that the more areas of inadequate support someone reported, the greater the likelihood of their experiencing burnout.

Good policies matter because, when put into practice, they support the people who make our libraries thrive. Creating safe work spaces and providing flexibility and access to paid leave and caregiver accommodations can reduce the likelihood of staff burnout, which in turn can reduce staff turnover and improve the library experience for all in the community. As we engage in the work of recovery, supporting staff means supporting libraries and communities.