The Impact of COVID-19 on Library Staff: Supporting Health and Well-Being

In 2020 the Public Library Association (PLA) and the American Library Association (ALA) conducted two surveys about the impact of COVID-19 on libraries. Following on from that, PLA’s “Survey of the Public Library Field” in February 2021 asked library staff about the impact of the pandemic on them as individuals. The survey received 2,967 responses. This post – and two to follow – presents the results of these survey questions and suggestions for how library leaders can make improvements to better support staff now and in future.

Challenges

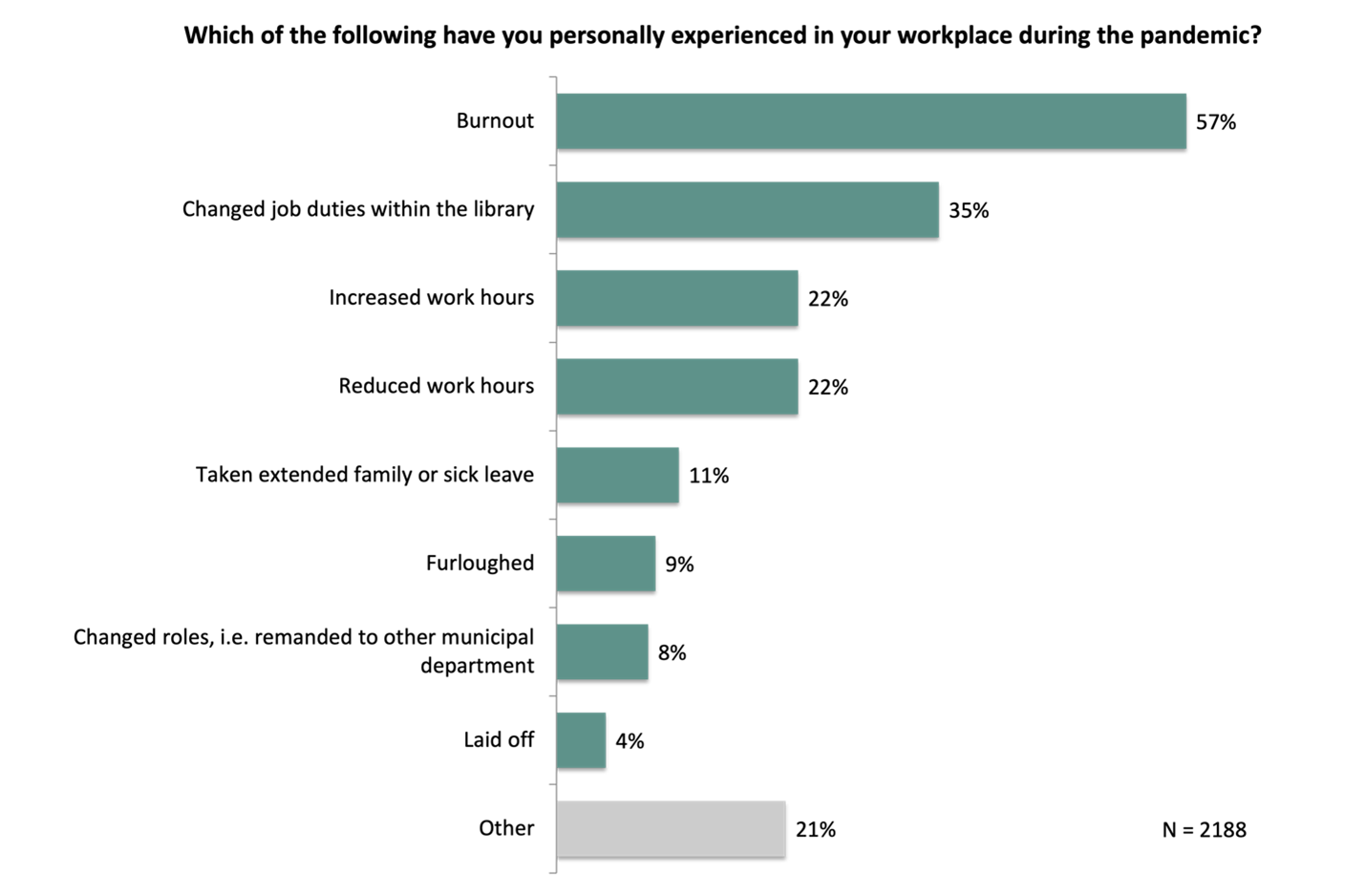

Library staff have faced a range of challenges in their work during the pandemic (chart below). As circumstances have changed and library buildings have closed and re-opened, 22 percent of survey respondents reported having reduced work hours, while the same percentage reported increased work hours; the two are not mutually exclusive. However, the numbers mask underlying differences based on roles within the library. Administrators were more likely to report increased work hours, while non-administrators were more likely to report reductions to their hours.

Overall, 9 percent of respondents reported having been furloughed and 4 percent laid off. Eleven percent have taken family or sick leave. Eight percent have changed jobs, such as moving to another municipal department, and 35 percent have had their roles change within the library.

By far the most common experience respondents chose was burnout (57 percent). Exhaustion, depersonalization or negative attitudes to work, and reduced effectiveness at work all characterize burnout, which results from “chronic workplace stress.” According to a report from Gallup, the factors most likely to correlate with burnout are unfair treatment, an unmanageable workload, unclear communication, lack of manager support, and unreasonable time pressures. In North American public libraries specifically, LIS researcher Kaetrena Davis Kendrick has found that common stressors include overwork, budget or financial challenges, problems with coworkers or management, and job precarity, among others. These contribute to burnout and to low morale more broadly.

The pandemic has exacerbated many of the factors that can lead to burnout. Health and safety concerns add stress, while social distancing has taken away some of the fun and the support systems. Increased workloads or cuts in hours and pay have added both mental and financial pressures. Those in leadership positions reported added stress from bearing the responsibility of staff and patron well-being, while dealing with the unknowns and uncertainties of the past year. One respondent wrote, “It’s been an incredibly challenging year and I am weary of making hard decisions.”

Libraries – like other workplaces – can implement policies and practices to mitigate the causes of burnout. A few common suggestions emerge from the research: listen to employees, value their opinions, and make changes based on their input; ensure workloads are reasonable; give staff flexibility and control over their work; recognize good work; and support employees to do meaningful work. While it is important for individuals to engage in self-care for their own well-being, that alone is insufficient. Improving policies can help all staff, including leadership, to thrive.

Supporting Staff

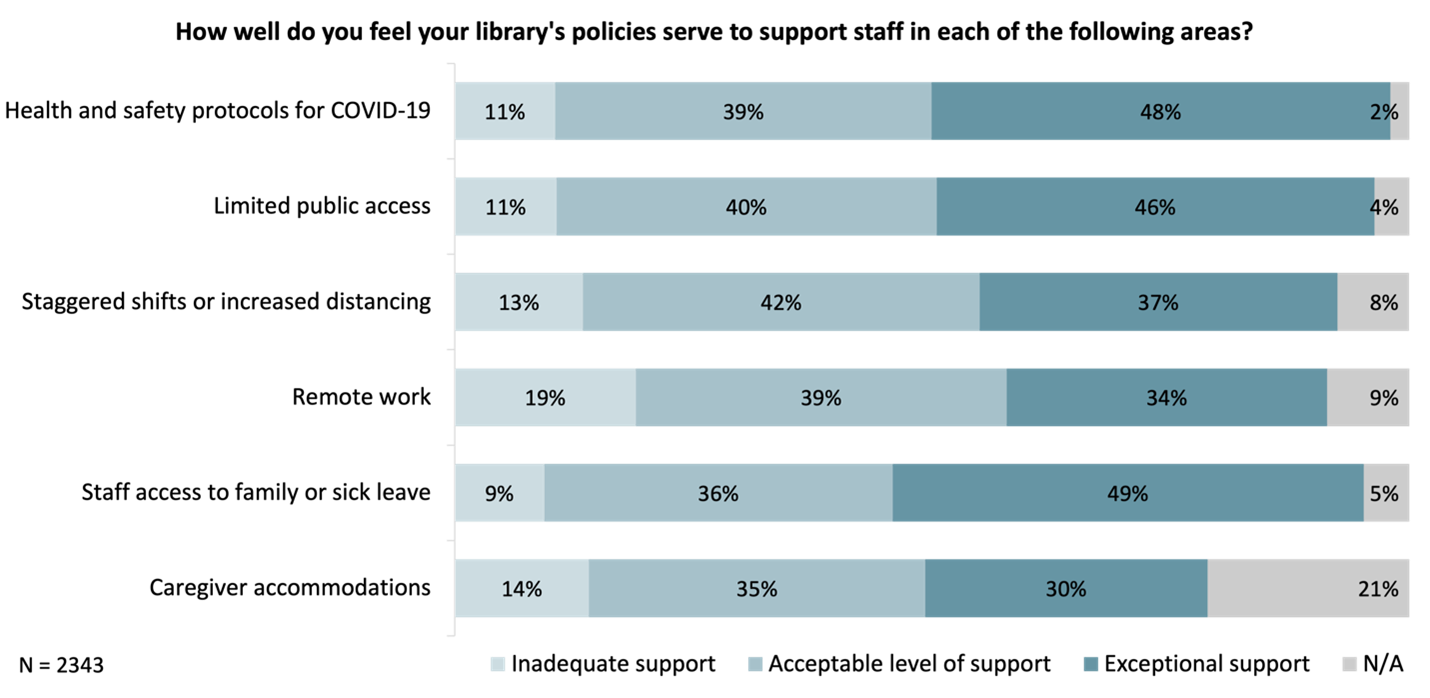

Another survey question asked how well current library policies support staff in six key areas (chart below): health and safety protocols for COVID-19; limited public access to the library for staff and patron safety; remote work; staggered shifts or increased distancing at staff work spaces; staff access to family or sick leave; and caregiver accommodations. Respondents could select inadequate support, acceptable support, or exceptional support.

The majority of respondents (eighty-seven percent) said their library’s COVID-19 health and safety protocols are either adequate or exceptional, while eleven percent said their library’s protocols are inadequate. Worst rated was remote work, with nineteen percent of respondents saying support is inadequate.

Libraries depend on people. For all staff to be the best they can be, they need support. What characterizes “inadequate” or “exceptional” support? And how can library leaders move to ensure that staff are exceptionally well supported?

The remainder of this article focuses on COVID-19-related protocols. Part 2 will focus on remote work, and part 3 will focus on access to family and sick leave and accommodations for parents and caregivers.

Health and Safety Policies

When it comes to health and safety, the best policies are the ones put into practice. Libraries need to not only establish policies that follow public health guidance to keep staff and patrons safe (as most have done), but they need to have mechanisms to communicate and enforce of those policies. Sometimes the library has the authority to set and enforce policies; in other instances, they are subject to mandates at the city, county, or state level, which themselves may not align with the best public health guidance.

This principle applies to interactions with the public as well as minimizing contact between staff working in the library. Many survey respondents reported limiting the number of staff in the building at a time, installing plexiglass shields between workstations, and ensuring masking and social distancing. The most creative solution reflected in the survey comments involved putting all staff into two or three small groups or cohorts. Each cohort works in the building for a few days at a time, and they do so in rotations, never coming into contact with other staff from outside their group. In the event of a COVID case, this would minimize the number of staff exposed.

From the survey comments, it is clear that staff feel scared and frustrated when policies and practices (or lack thereof) may needlessly expose them to the virus. The reverse is also true: respondents who said their libraries provide exceptional support felt all staff had a trusted role in decision-making and the resulting practices help both library staff and the community stay safe. While acknowledging the many challenges, respondents used words like “supportive,” “caring,” “flexible,” “accommodating,” and “proactive” to describe exceptional policies and practices in response to the pandemic.

Those terms should also apply to plans to resume regular services. With vaccinations increasing, we can see the light at the end of the tunnel. Hopefully soon libraries once again can welcome everyone, all the time, to browse, gather, and learn. It will take time to adjust. When it comes to supporting library workers – and thereby supporting libraries and each other – let’s ensure that we learn from the experiences of the past year and carry those lessons forward.