Revolting Librarians: Fifty Years Later

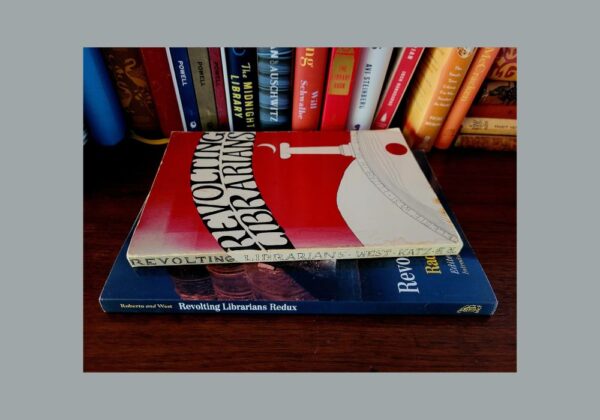

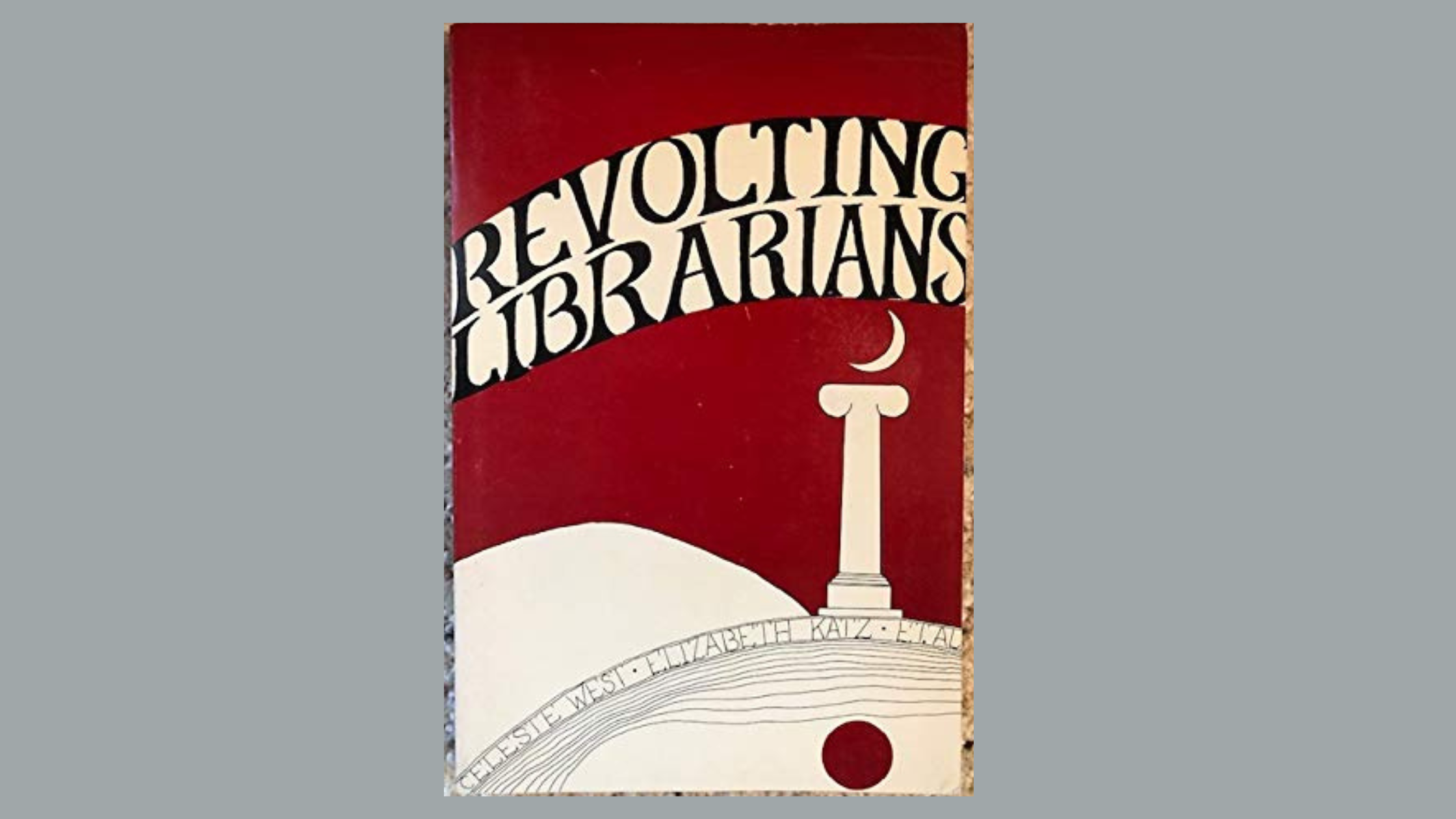

Fifty years ago, a group of self-described radical librarians published a manifesto: Revolting Librarians. Edited by Celeste West, Elizabeth Katz, and Anne Osborn, it’s described by the popular reader’s website Goodreads as “…one of the lasting monuments of the library underground.”

The book includes freewheeling essays by library staff from around the United States and Canada on progressive topics ranging from outreach to migrant worker communities to combating pay inequity. It’s fascinating to read in 2022 what radical librarianship looked like in 1972- when this book was self-published in typewriter font and sold for $2 a copy by mail order. A lot has changed, but even more has stayed the same.

Librarians 50 years ago called out the disconnect between library workers on the frontlines and those who call the shots (top-down administration), die-hard shushing stereotypes, and systemic inequities that thwart access for many users. Others complained of irrelevant library school curricula and the difficulty of introducing new ideas into bureaucracies. Many of these issues linger.

In “Doing it: Migrant Workers Library,” Martha Powers Williams writes as one of two librarians in New Jersey who spent their own time providing weekly outreach at a migrant workers’ marketplace. She describes how important it was to reach people who wouldn’t otherwise make it to the library and laments that this couldn’t be part of their regular jobs. This hasn’t changed much. Outreach beyond library walls to underserved communities, despite some laudable examples, remains sparse- and pandemic staff shortages haven’t helped.

Likewise, many of the issues raised in “Trails of a Paraprofessional” by Judy Hadley, still ring true. Paraprofessionals often feel unseen and undervalued and note that they do much of the same work as librarians without the title or compensation. Simultaneously, several of the essayists question the value of the MLS degree, as summarized in “Library School Lunacy” by Harleigh Kyson.

Improvements have occurred in the field, however: better understanding of the need for specialized teen service librarians and quality children’s services in general, progress in inclusivity when it comes to Library of Congress subject headings, and expanded publication and acquisition of works by diverse authors. “Homophobia in Library School” isn’t at the level as it was when Bianca Guttag wrote her essay by that title for the 1972 volume, fortunately.

Technology is the aspect of the field that has changed the most, unsurprisingly. The 70s era essays include some mention of computers, but when referring to the catalog, most are referencing drawers of hand-typed cards. Some of the writers complain of the tedium of typing and filing tasks- since replaced by digital vexations. However, most of the contributors skirt the issue of technology, or mention it in passing- perhaps anticipating rapid change would soon render analysis of those aspects of the field obsolete.

Revolting Librarians has historical value as a primary source of 70s era radical librarianship. Readers may grin at the quaint struggles with card catalogs and typewriters while relating with age-old frustrations such as the inadequacy of the library to serve as a Band-Aid for systemic inequities. Due to outdated slang and references to obsolete technology, this book will probably never be reprinted. It also has not been digitized.

It’s easier to get a hold of the 2003 sequel, Revolting Librarians Redux: Radical Librarians Speak Out, edited by K.R. Roberto and Jessamyn West. Ten of the 56 contributors are essayists from the original volume who are “still revolting after all these years.” While the sequel is not the same time travel experience as the original, it’s peppered with poetry, cartoons, and drawings like the first volume. This sets it apart visually as well content-wise from stodgier professional publications.

In the 1972 book, Art Plotkin wrote “The Liberation of Sweet Library Lips” about his campaign to fill libraries with “No Silence” signs in defiance of shushing stereotypes. For the sequel he writes: “Silences being imposed on libraries lately have less to do with sound than with content and privacy rights, and are much scarier.”[1]

Indeed, many challenges aren’t new, they have just shape shifted. And progress has occurred, however slow and incremental it may seem. Vintage library lit reveals how forward-thinking librarians contributed to making that happen.

References

[1] Roberto and West, eds. Revolting Librarians Redux, p. 19.

Further Reading

West, Celeste and Katz, Elizabeth, editors. Revolting Librarians, San Francisco, CA: Bootlegger Press, 1972.

Roberto, K.R. and West, Jessamyn, editors. Revolting Librarians Redux: Radical Librarians Speak Out. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2003.

*Opinions expressed by the author are her own and not meant to reflect those of her employer or any other individual or entity.