“I Was On A Treasure Hunt” – Ann B. Parson On Her Fascinating Debut Novel

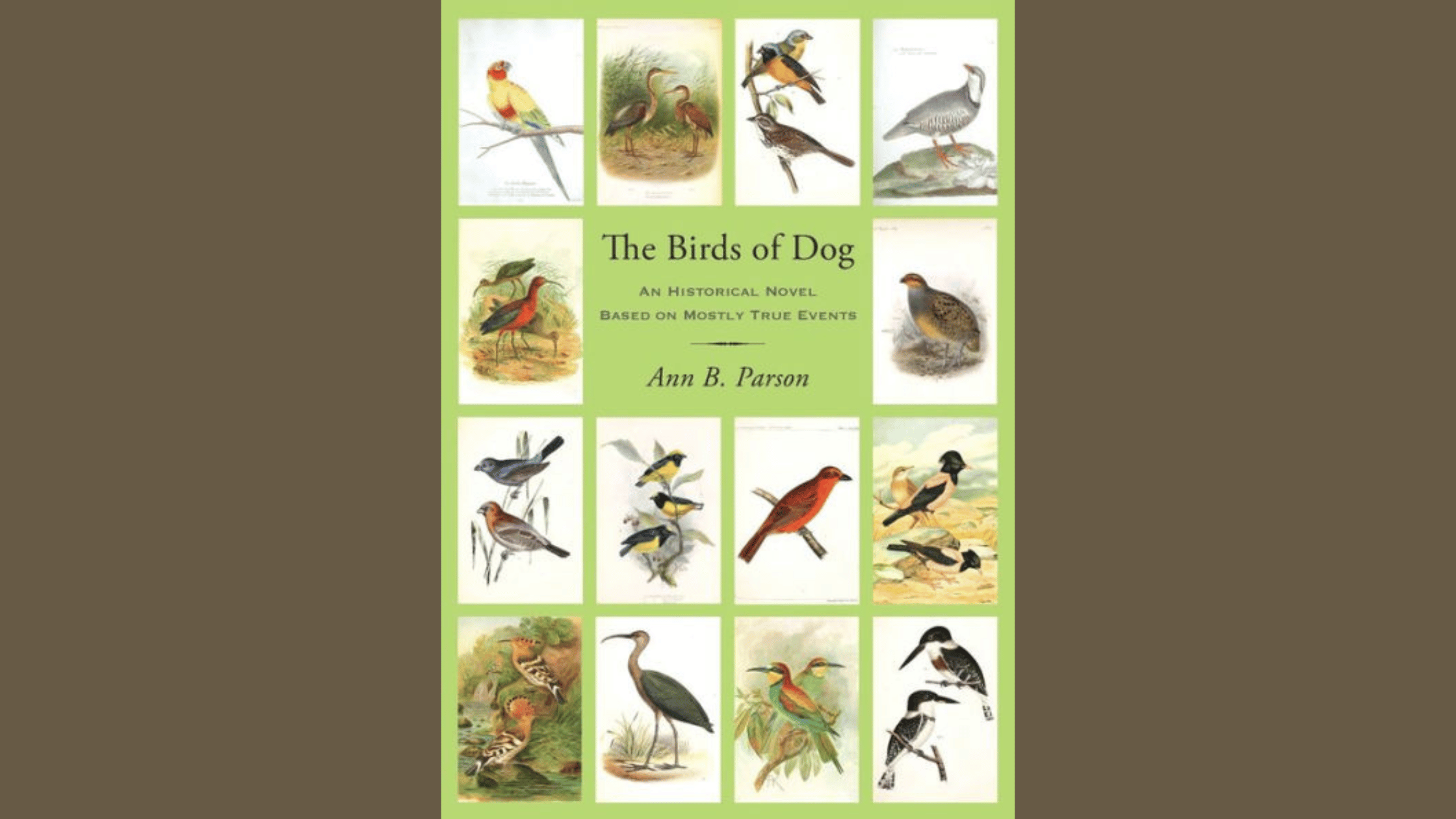

Readers hungry for historical fiction will find lots to savor in Ann B. Parson’s The Birds Of Dog. Parson, an accomplished science journalist and author of several nonfiction books, lends her journalistic acumen to this tale centered on Catherine Pickering, a curator’s assistant at Boston’s Society of Natural History. Catherine is a fictional member of Massachusetts’s very real Pickering family, whose members included many notable scientists. The Birds of Dog takes form in a series of letters written between Catherine and her cousin, Charles, an acclaimed zoologist who has been dispatched on an exploratory mission to the South Seas. Through their correspondence, Parson immerses the reader in the world of nineteenth century Boston, highlighting the rapid technological changes of the era, the complicated association between hunting and scientific research, and Catherine’s developing relationship with the famed inventor James Cutting. Readers will fall under the spell of Catherine, whose reverence for the natural world and innate curiosity to better understand it propels the novel. Parson spoke with us about her introduction to the Pickerings, delving into the nineteenth century scientific world, and how working on the book was like being on a treasure hunt.

You wrote another book where you researched the Pickering family, and I’m curious to hear how that book led to this novel.

There are a couple of things that led me there. One is, as a science journalist, I’ve always had a strong interest in the history of science. After three commercial books, I went and did five commissioned books, one of which was about the Pickerings in Salem. I was working on that fifteen years ago. I realized that back in the early 1800s, as many as three, if not four, Pickerings were scientists. This was so far back that the word “scientist” wasn’t even in use yet; the term “scientific” was used. One of those Pickerings was Charles Pickering, a leading naturalist in America. He was born in 1805, and in 1838 he was asked to go out on this big US exploring expedition to explore the Southern Ocean, the South Seas. I’d just started coming across all these related stories with a Pickering scientist and with the Boston Society of Natural History—which they all belonged to—and I had more and more questions as a researcher. Why did the Boston Society of Natural History begin? It eventually became the Boston Science Museum today. One thing led to another. Mostly I wanted a way to save a lot of interesting stories under one roof. I found the story about how the early sciences in America started to be really interesting. No one’s really written that story, so I went leaping down that rabbit hole.

It’s remarkable to see how the field of science has changed. Today, research seems so specialized, while your characters seem to cover a wide range of interests.

That was huge. I mean, Charles Pickering is a perfect example. He was a naturalist and went in every direction. Back in those days, there were no subdisciplines, though they formed very quickly. He was a zoologist, he was a conchologist, as in shells. I can go on. He was about ten different things,

That leads me to Catherine, who’s such a captivating tour guide for the reader through this time period. All the other characters existed in history, and you invented Catherine. Can you talk about how you went about creating her and how she fits into this world?

That’s a good question. Some people don’t realize Catherine’s invented, so thank you for noticing. She’s sort of a vehicle. She sounds like me, in a way. Part of her is very much me, but I began forming the idea for this story in my mind of how a curator’s assistant would be corresponding with her cousin, who was on this great ocean voyage. She would be home at Boston and meeting all these naturalists and scientists coming through the door, though they weren’t called scientists yet. She’d be writing about them and other stories connected to science and technology that were happening in Boston. There were a ton of stories going on in those days. She’d write to Charles and say, “Guess what? Daguerre just announced his invention,” or “Samuel Morse just announced his invention.” All these inventions were happening back then. I saw that as a good structure.

Then I have a second narrative further out, speaking back from the year 1895, because if you’re writing a letter and you tell a story, you can’t tell the whole story in the letter. I realized I was coming up short with stories. But with this voice that looks backwards, he comes in, and it’s a braided narrative. He fills out each of these stories that I’m telling in the book.

Even though, as you say, she’s a vehicle, she really comes alive on the page, and she’s such a three-dimensional character in her own right. I think readers will really fall in love with her voice in terms of how she gets across her opinions about and how passionate she is about her pursuits. Can you talk about how that aspect of her character came to light?

It’s really nice to mention all that. I had her starting out kind of innocent and a little naive. She grows to understand that she doesn’t like what she’s seeing. That’s basically throughout the book. I try to do this overarching theme of technology versus nature. The more technology gets invented, the more it’s at odds with nature. She sees this more and more with guns and gets to quite dislike all the hunters who are going out and killing all these birds, including Audubon, who I might mention is in the book. She’s just her own free will person. She gets more and more involved with wildlife, so that’s interesting to me.

Through Catherine’s perspective, we see this tension between the scientists who are hunters and believe that the only way to study a bird is to kill it, and the scientists who envision a different way of researching birds. I was curious to hear you talk more about that tension between the two camps.

I constantly felt when I was working on this book that I was on a treasure hunt, because I would go back to the past and find these stories. As I defined what I was up to, I looked for stories that had to do with technology versus nature. One of the stories that fascinated me was a story about this Reverend in Scotland. He had a goose, who he loved, that followed him to church every day. On the other hand, like all the men of his era, he loved to go out to hunt. He’d go out to hunt and he kept missing birds because he was using a flintlock gun mechanism, which made little puffs of smoke that scared the birds and made them fly away. He decided he was going to make a better gun mechanism. He invented the precision lock mechanism for guns, which didn’t create a puff of smoke from gun powder. It was a precision lock, I believe. It’s been a while since I’ve researched this, but it’s more friction creating a spark so there’s no puff of smoke. He was able to kill more birds that way. The awful part of this is that this precision lock weapon eventually landed on battlefields, both abroad and here. It’s innocent what happens with technology. You think you’re improving life, but it can backfire, pun intended. That was sort of the pivotal moment for me to find that story really confirmed that I don’t like guns, and I love nature like most people. It confirmed for me that I was at least on the right trail.

That story is so powerful and sets up so much of the ideas that the characters are all wrestling with. One thing that I was struck by was how a character like Audubon changes over the course of the book. I think readers might have one view of Audubon, but they get a more complete vision of him from your book. Can you talk about why he appealed to you and why you wanted to include him in the book?

Again, my starting point for a lot of this was the Boston Society of Natural History, and he was an early honorary member. Though he didn’t live in Boston, he came to Boston a lot and knew a lot of the families. Everything I read, it was so obvious that he was a pretty good looking, arrogant guy. I wish I could see him in person. You’ve seen his portrait on the front of many books. He had these long, dark locks, and dressed beautifully. Not to give things away, but the more I read, I was thrilled to realize that he changed as he got older. I’ll just leave it at that.

I ended up creating endnotes for this book, which is kind of unusual in fiction. I was scared I would forget where I found this information, and I wanted the reader to know. I’m not sure, I might have made endnotes for myself! (laughs) Anyway, he did change, and Catherine begins to like him better by the end.

It was so fun to see all these different historical figures, like Dickens and Thoreau, pop up in the novel. Was there a particular figure you were especially delighted to be able to work into the story?

They were all interesting. I devote part two towards the end of the book to James Cutting. He was an amazing person, and he’s been entirely forgotten, along with Charles Pickering and other scientists. He was an amazing person. He made a small fortune in business early in Boston, and then turned to inventing. I’ll just briefly say he actually started the first standalone aquarium in the world on Bromfield Street in downtown Boston. Nobody knows this. It was a street that I used to walk down a lot as a kid. It was almost a street out of Dickens. It was filled with little shops: watchmakers and pawn shops and all these things. Cutting actually brought aquariums into the modern age by inventing something called Cutting’s Aerator. He got into trouble at one point, his pools of water with fish began to sort of cloud over with a lot of debris, and he realized that the way of getting oxygen into the water didn’t work on a bigger scale. He invented an aerator, which really brought aquariums forward. That was in the 1840s, 50s. Before that he made a fortune off inventing ambrotypes, a type of photograph. He’s really a thrilling character.

There are so many little details that make the novel spring to life. I think readers will enjoy scouring your endnotes.

One way I found a lot of those stories was there was a period of time that Gail Research Database was free to researchers like me. I could sit at home and open up the database on 19th century newspapers and do a search of the Boston. There were a lot of newspapers back then—Boston easily had twenty to thirty. I could do search words like “Audubon” or “giraffe” or “birds” and up would come these little stories. That’s where some of my little stories come from. It was awesome to be able to research that way.

Without giving too much away, can you talk about how you came up with the title of the book, The Birds of Dog?

Going back to Charles Pickering’s voyage to the South Seas, he and others landed on this little dot of an island called Dog Island. Apparently it’s within a bigger chain called The Disappointments. Don’t you love that name? They knew from other travelers that no guns had been shot on this island. As soon as they got on, they noticed all the animals were really tame, especially the birds. They would land in your hand if you offered them bread. You could pick them off the nest for their eggs. Here all this wildlife was very tame because no guns had been shot on that island.

Finally, what role has the library played in your life?

Gosh, you’ll notice in the back of the book, that’s primarily who I thank, libraries and librarians. I’ll tell you, my great grandfather began a library with two other gentlemen in a little town in Maine, and that library has stayed very central in my life. It’s called Friends Library in Brooklin, Maine. I belong to the Boston Athenaeum in Boston. The library here in South Dartmouth is fantastic. Libraries are so cool in the way they’ve jumped over the digital hurdle and embraced the digital world. A lot of them have become richer resources than ever. I can’t think of another place I’d rather spend an hour than a library. Or a day, because how can you just go for an hour?

Tags: Ann B. Parson