Transforming Library Catalogs: The Promise and Challenges of Linked Data

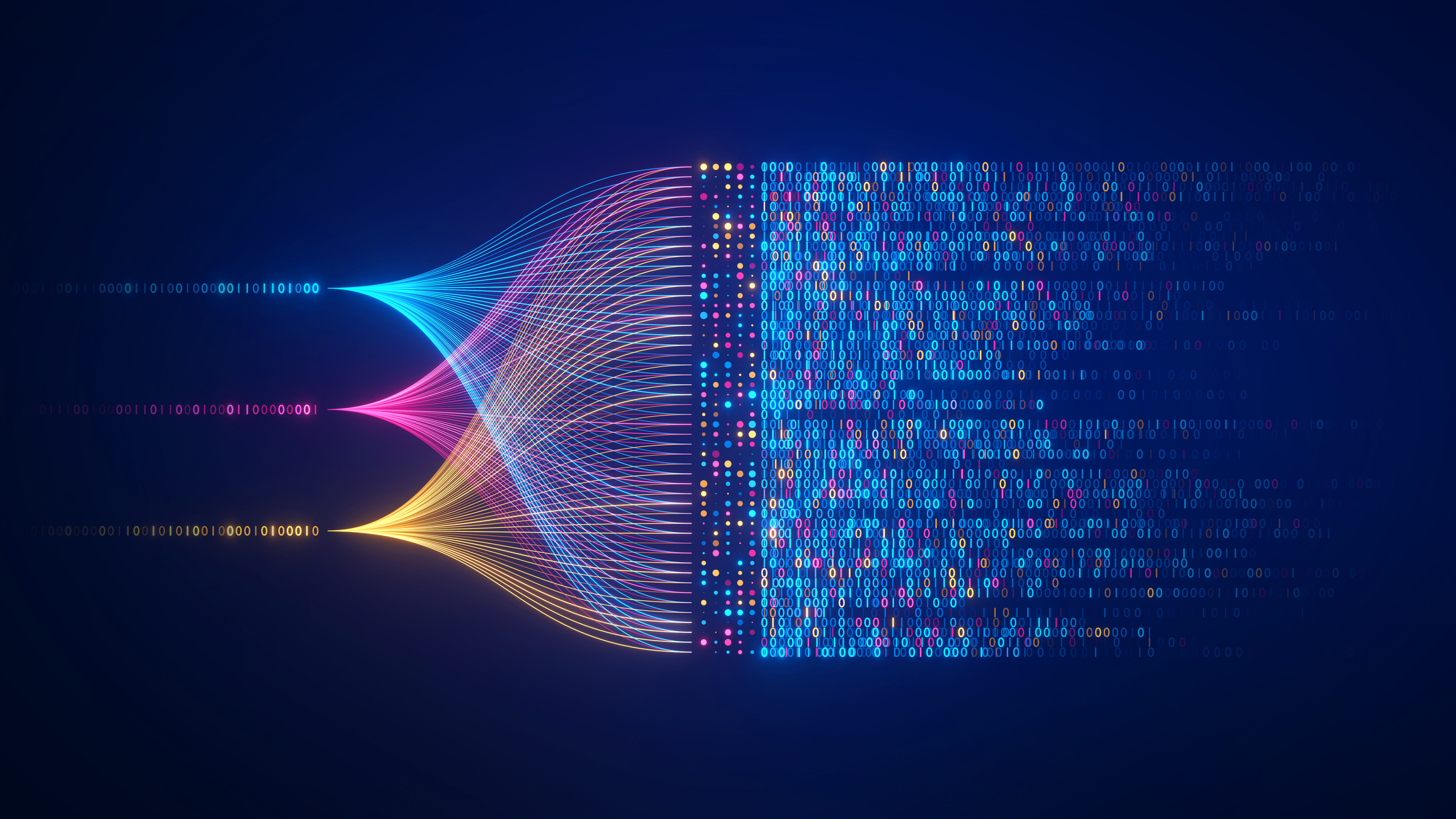

Originally conceptualized by Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world wide web, linked data is a system of organizing information with the goal of making it easier to share and find new information (1), something which is very appealing to libraries. While library users are changing rapidly, methodologies for cataloging library materials are very slow to change. After the development of Machine Readable Cataloging (MARC) in the 1960s, the only major update was the online catalog in the 1980s.(2) Catalogers have long been asking for change (see: “MARC Must Die” by Roy Tennant in 2002 (3)). Finally, in 2011, the Library of Congress (LOC) began the process of switching to a linked data model for bibliographic resource description. (4)

Linked Data and Patrons

Linked data models focus on relationships to describe materials rather than subject headings and authority records (5):

[Octavia E. Butler] <is the author of> [Parable of the Sower] …

[Pasadena, California, USA] <is the birthplace of> [Octavia E. Butler]

Databases of these relationships are connected by http links (URIs) in the bibliographic records (6):

100 1 Jemison, Mae, ǂd 1965- ǂe author ǂ1 http://id.loc.gov/rwo/agents/n95004729

The URI connects the person, Mae Jemison who was born in 1956, to data associated with NASA, being a woman, being an African-American, Alabama (where she was born), Cornell University, etc.

Imagine a student researching Mae Jemison. Currently, the library catalog will return materials with “Mae Jemison” in an authority field, subject heading, or in a keyword-searchable MARC field. In a linked data-enabled catalog, the search would produce additional results based on the relationships listed above. The student could discover information about Alabama in the 1950s or African-American engineers or astronauts in general and, with access to external databases, could connect to sources like the National Archives. All of these results could, potentially, be returned with the single search.

In fact, linked data already helps patrons everyday. Search engines like Google use “schema.org structured data” (a specific linked data methodology) to create knowledge panels in search results. (7) A Microsoft Bing search for “suffragette” will produce images from the Buckingham Palace demonstration of 1914, snips from the Wikipedia page, articles about the 19th amendment, links to actors from the Suffragette film, and so on.

One of the challenges is getting online search results to include library information. Richard Wallis from Data Liberate presented at a 2015 SmartData conference about OCLC’s efforts to extend the benefits of Schema.org with bibliographic data (8) and, according to Jeff Mixter at OCLC, “OCLC works with organizations like Google to insert library linked data into their services.” (5)

Public Libraries and Linked Data

Converting libraries to a linked data system is complicated. These days catalogers typically don’t have the capacity, authority, or software to test out new cataloging methods. Additionally, not all ILS discovery platforms used by public libraries have incorporated linked data into their search results and it can be difficult to convince budget-strapped library leaders to spend money on training staff for something they can’t use yet.

Kyle Banerjee at OHSU argues that libraries don’t have the resources to maintain the metadata needed for linked data, that it is more “appropriate for limited domains that can be described using well-maintained vocabularies,” such as drug research. (9) Jeff Edmunds at PennState wrote that “the future lies elsewhere, with full-text indexing, big data, and increasingly impressive AI systems…” (10)

Nevertheless, libraries around the world are converting to linked data, especially archival repositories like the national libraries of Spain and Sweden and academic libraries like Stanford and Cornell. (11, 12) Interviews with library professionals at the National Library of Sweden – one of the first libraries to adopt the linked data model – suggested they see the benefits of the change and “while there are still many challenges and obstacles to tackle there is a strong belief that the advertised promises of linked data will come true in time.” (11)

According to Innovative (which owns Polaris and Sierra ILS) a few public libraries are starting the transition too, including Denver PL, Dallas PL, Multnomah County Libraries, and San Francisco PL. (13) Vendors for ILS and discovery platforms created software for converting MARC records to linked data in efforts stay competitive in the market. “This makes your library’s resources and location information readable by search engines… It takes your metadata and puts it on display in front of people searching for information. It’s minimal effort for staff, and big visibility for the library.” (13)

In other words, library staff may not be ready for the transition to linked data ontologies but library leaders and vendors are moving forward. Take a moment to browse some MARC21 bibliographic records and you will see URIs everywhere. Linked data cataloging (“catalinking” (14) is in progress and, like many things library-related, contentious.

References

References

- Berners-Lee, Tim. “Linked Data.” W3C Design Issues (accessed January 3, 2025). https://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html.

- Coyle, Karen. “The Evolving Catalog.” American Libraries Magazine (January 4, 2016). https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2016/01/04/cataloging-evolves/.

- Tennant, Roy. “MARC Must Die.” Library Journal (October 15, 2002). https://soiscompsfall2007.pbworks.com/f/marc%20must%20die.pdf.

- Frank, Paul. “BIBFRAME : Why? What? Who?” (May 1, 2014). https://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/bibframe/BIBFRAME%20paper%2020140501.docx.

- Mixter, Jeff. “Introduction to Library Linked Data.” OCLC Next Blog (accessed January 3, 2025). https://blog.oclc.org/next/intro-to-library-linked-data/.

- “Thing 20: Linked Data and MARC Records.” 23 Linked Data Things (accessed January 3, 2025). https://minitex.umn.edu/services/professional-development/23-linked-data-things/thing-20-linked-data-marc-records.

- Google Search Central Documentation (accessed January 3, 2025). “Introduction to structured data markup in Google Search.” https://developers.google.com/search/docs/appearance/structured-data/intro-structured-data#:~:text=In%20addition%20to%20the%20properties,if%20they%20are%20deemed%20useful.

- Wallis, Richard. “Schema.org — Extending Benefits.” Data Liberate (accessed January 3, 2025). https://dataliberate.com/2015/08/25/schema-org-extending-benefits/.

- Banerjee, Kyle. “The Linked Data Myth.” Library Journal (August 13, 2020). https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/the-linked-data-myth.

- Edmunds, Jeff. “BIBFRAME Must Die.” PennState University Libraries (October 15, 2023). https://scholarsphere.psu.edu/resources/fc19faee-70b9-44b3-9346-18e40a2cd990.

- Unterstrasser, Julia. “Linked Data and Libraries : How the Switch to Linked Data Has Affected Work Practices at the National Library of Sweden.” Uppsala Universitet (2023 Dissertation). https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1773893&dswid=-4742.

- Library of Congress (accessed January 3, 2025). “BIBFRAME 2.0 Implementation Register.” https://www.loc.gov/bibframe/implementation/register.html.

- Innovative Interfaces, Inc. (accessed January 3, 2025). “Linked Data.” https://polaris.iiidiscovery.com/?page_id=1203.

- Wallis, Richard. “Linked Data for Libraries: Great Progress, but what Is the benefit?” SWIB 2013, Hamburg. https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/linked-data-for-libraries-great-progress-but-what-is-the-benefit/28630987#1