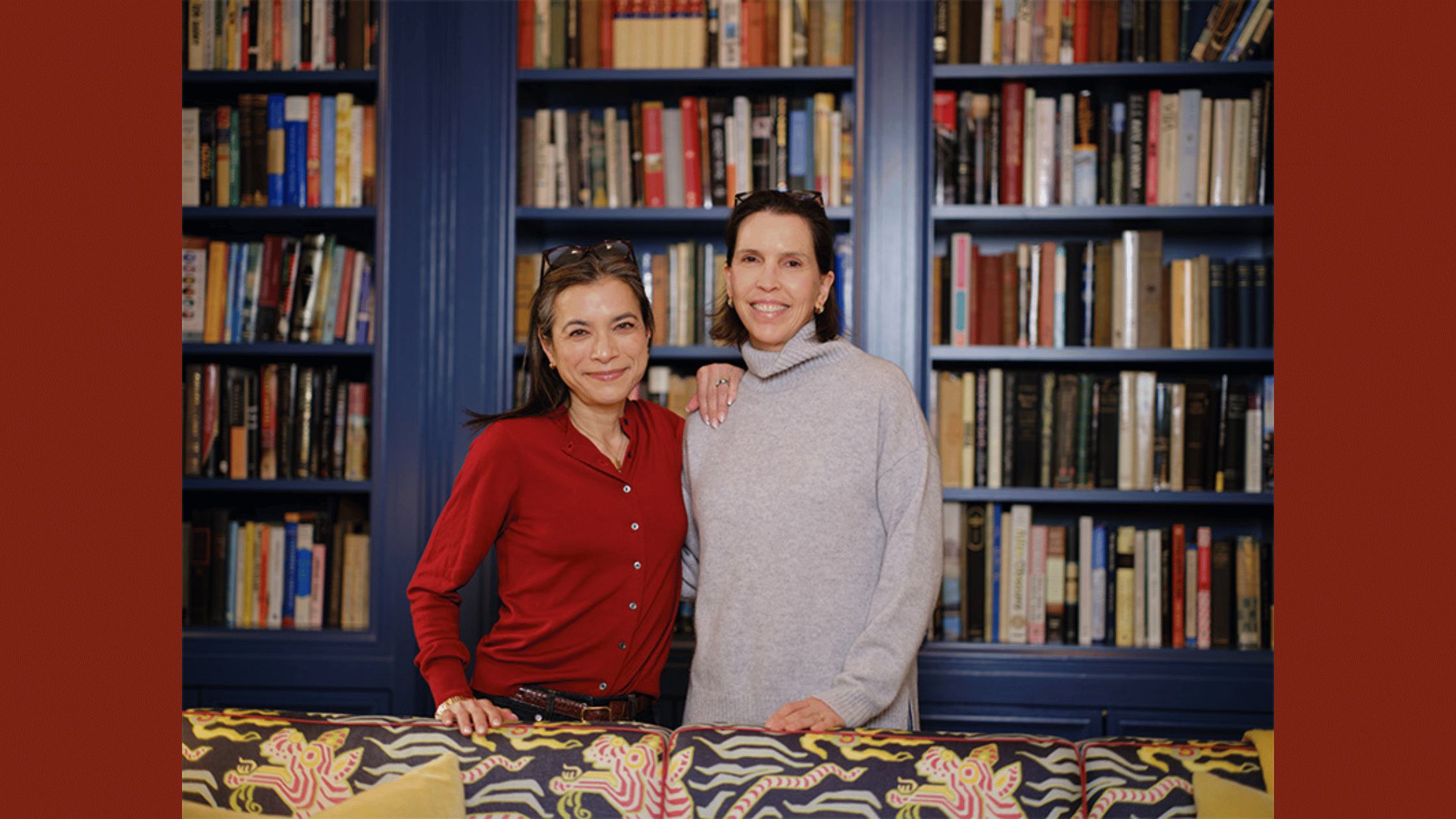

Lisa Cooper And Bremond Berry MacDougall On Influencing The Literary Canon With Quite Literally Books

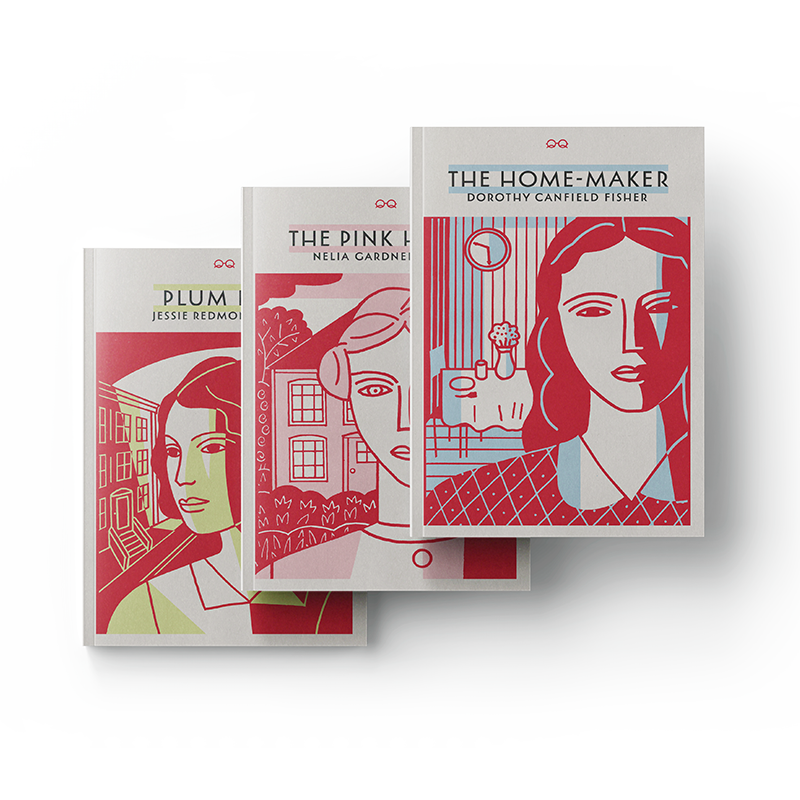

Lifelong friends Lisa Cooper and Bremond Berry MacDougall turned their shared passion of reading into Quite Literally Books, a publishing company designed to draw attention to critical works by authors who have not enjoyed the lasting critical attention they deserve. Their first three books—Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset, The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher, and The Pink House by Nelia Gardner White—are all terrifically engaging novels primed to be rediscovered by readers. With the reissuance of these books, Cooper and MacDougall hope to spark a conversation among readers about who gets included in the literary canon and who gets left out. We spoke to MacDougall and Cooper about how their company came about, plans for future books for the company, and how reading gives people permission to talk about difficult topics.

How did the two of you come together to found this company?

Lisa Cooper: The two of us came together in Austin, Texas, in like 1982 or something. We were twelve years old. I was the new kid in school, Bremond was kind enough to take me under her wing, and we became best friends. From the get-go, books were a really big part of our friendship. I had honestly never met anyone else who read as much as I did, except my dad. Bremond probably outreads me now. She’s shaking her head and saying no, but I actually believe she does. (laughs)

We’ve always loved to read, and we’ve always loved to talk about what we’ve read. There were many, many years when we were in different places, raising families, having jobs and not really in that much communication. Bremond’s a notoriously bad responder to texts. But I would be sitting in a bookstore across the country and text her, “What should I buy? What are you reading?” She’d always text me back if it was a question about books. So that has always been a big cement of our friendship.

Bremond Berry MacDougall: During the pandemic at the beginning, when everybody was at home and had too much to do and also not enough to do, and too many people, and also not enough people, Lisa and I were talking more often. We were talking about books and what we were reading, because that was top of mind at that point, and we just sort of talked and talked and talked ourselves into starting a publishing company.

LC: It started because we both turned fifty, and we were like, “Okay, what are we doing next?” It was a good time to reassess.

BBM: Our kids were getting older. What are we going to do?

LC: What do we want to focus on? Books seemed the obvious choice, right?

BBM: Books seemed the obvious choice, publishing probably less so. (laughs) But that’s where we landed.

LC: The notion that we could influence the American literary canon in some small way felt really interesting to us. We’ve always been big readers of old books, and oftentimes we’ll read something and ask, “Why doesn’t anyone know about this? Why isn’t this like part of the canon?” That’s come up over and over again.

So that was a big part of it, this idea of being able to have a say and to hopefully get other people talking about these things too. Obviously, there are academics out there who know way more than we do about all this stuff. And people do have these conversations, but I don’t know that they happen with regular people, regular readers—

BBM: —the person that you see at the coffee shop—

LC: —and we find that to be really interesting.

With all the books that could potentially fall under the rubric of what you’re looking for, how do you select the six books you’ll publish each year?

BBM: It’s not a very scientific process at this point. Hopefully over time, it will become more so. We’re hoping that people will bring things to us, that people will say, “Gosh, I read this book when I was younger. I love it, it’s out of print, and I would love for people to be able to buy this book.” But from the start, for the past couple of years, we have looked at book reviews on the Times Machine, on The New York Times archive. We’ve looked at lists. There are a million lists online of “Forgotten Books.” We look at what the Book of the Month Club was publishing, things like that. We also spend a lot of time at The New York Society Library, which is a subscription library here in New York City, which we don’t think has thrown away much—

LC: —since 1754, we’re pretty sure they’ve kept almost everything. (laughs)

BBM: There are routinely books on the shelves that are from the early 1800s, and sometimes we just hang out in the stacks and find a book. It’s how we found The Pink House. Nelia Gardner White wrote about twenty-five novels in the 40s and 50s. She takes up the better part of a shelf in the library. We thought, “Oh, look, Nelia Gardner White. I wonder who that is.” You pick up a book and find out, “This is really good.” Sometimes that happens.

LC: That actually happens quite a lot. It’s interesting, because we do love just hanging out in the stacks. That’s part of it. There aren’t many other places we’d rather be. On a cold day or a hot day, the library is always the perfect temperature. We go to the library and we scour the shelves, and then pull out our handy dandy phones that actually don’t work very well in that particular library. (laughs) We look up these authors. It’s not scientific, but it actually works more often than you might think.

BBM: We also find stuff in used bookstores. I have a big personal library that includes things from lots of different sources, so I don’t really know some of what I have. We look at stuff that I have on my shelves that might be interesting. We’re trying to stick to American authors at this point. That’s sort of our focus, so that narrows things down a little bit.

Bremond, in the press release, it says you have a collection of over thousands of books, that you refer to as a “readers library.” Can you talk about what is a reader’s library?

BBM: Well, I say it’s a reader’s library, as opposed to a collector’s library. I don’t care about first editions; I don’t care about any of that sort of stuff. They’re not valuable books. They’re just books to read. People borrow them, and sometimes they come back, sometimes they don’t, and that’s not the end of the world. I probably have four copies of Huck Finn, and every now and then a kid, or a friend of a kid, wanders through and needs a copy of Huck Finn for their class right now, and I’ve got it. (laughs) I have both of my grandmothers’ books, I have the remnants of a used bookstore in Maine. Then I have just the stuff that I have collected.

LC: She’s like the New York society library, she doesn’t throw anything away. (laughs) And also one of your grandmothers was a librarian, right?

BBM: Yes, she worked as both a school librarian and a city librarian at the Austin Public Library.

Besides exploring The New York Society Library, how else do you discover your books and authors?

LC: Plum Bun came about because I was curious about the Harlem Renaissance time period. We were looking to see who was a contemporary of Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen. Once we started going down that research rabbit hole, Jessie Redmon Fauset would come up. It was very hard to find anything on her. There’s stuff on the internet, but I wasn’t finding a good biography or anything. It turns out that she was a really important figure as part of the literary scene of the Harlem Renaissance. I believe she wrote four books total. We found Plum Bun, which is out in the world, but it hasn’t been republished in a while. We were like, “How come we’ve never heard of this person and her books are so good?” It was some focused research. That’s one of the things that we do, we look to see who are the people that we know about and then who else was writing at the same time. That’s one of our research methods.

All of your books seem primed for reevaluation in a really exciting way. How were they received when they were first published?

LC: All three were well received at the time they were written. Jessie Redmon Fauset’s Plum Bun didn’t get as much attention, but I think it was well received. Nelia Gardner White wrote a bunch of books that were commercially successful. We read something where her editor grouped her with Saul Bellow and all these other titans.

BBM: We were like, “Where did she go?” The Homemaker also was one of the most successful books the year that it was published in 1924. Our idea is that these books have not lasted or gotten the attention they might have because they concern women’s inner lives.

LC: They’re about the home, they’re about relationships. They’re about the interior lives of women. Even though we’ve sort of moved away from this idea of “chick lit,” I think that sensibility still exists today. It’s not always considered serious literature. Also, I don’t think that men pick these books up to read. It’s women writing for women usually, whereas, when men write for men, that doesn’t stop me from picking it up, right? We read it all the time, and we don’t think about it. I don’t know why this is, I think this is a societal issue. Men don’t tend to be drawn to these books. You cut down on the readership by a lot when that happens.

Can you talk about what the the other books that are on tap for being published this year are?

LC: We’ll share one with you, only because it’s the only one that we’re absolutely positive about, which is Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. We know that that is also something you can find, but we love that book. We wanted to give it a fresh cover, a fresh look, and hopefully introduce it to a different audience.

BBM: I’d never heard of it. I’d never read it before we went to the library, specifically looking for that author.

LC: I think most people know Charlotte Perkins Gilman because of The Yellow Wallpaper. We thought, “Okay, that was a very interesting book to come from that time, and definitely about the interior life of a woman in an extreme way. What else did she write?” And that’s how we happened upon Herland. It’s about a feminist utopia. It’s a land that’s only populated by women, and then, of course, men discover it. What happens when that happens?

You just mentioned the book covers, which are so beautiful and striking. Can you talk about working with the artist to develop the aesthetic for the books?

BBM: Thank you for saying they’re beautiful because we think they are too.

LC: We’re kind of in love.

BBM: Our designer, Louise Fili, who designed our brand, connected us with Anthony Russo. He’s an illustrator who’s pretty well known. He does a lot of work for The New Yorker and The New York Times.

LC: Bremond and I get really nerdy over kind of random things. A book that we were reading referenced Rockwell Kent and then that made us go, “Who’s Rockwell Kent?” We looked him up, and his engravings are incredible. We completely fell in love with that aesthetic, and we happened to share that with our designer, who said, “Oh, I have the illustrator for you.” That’s how Anthony got involved.

Basically the process was we pulled images that we thought were strong in each of the books. It just so happened that in this set of three each had a strong female protagonist that stands out. It made sense to feature a portrait, and then in the background you see a key image from the book. In The Homemaker, you see a clock, because time is such a big factor in that book. Obviously The Pink House has a pink house in the background because the house is mysterious and full of secrets. Then Plum Bun has the brownstones.

This is a question I probably should have asked at the beginning, but how did you land on Quite Literally Books for the name of your company?

LC: Because that’s literally what we do. (laughs)

BBM: It wasn’t that easy.

LC: It wasn’t. We thought of so many random, strange names and then, quite literally, one night, in a flash of inspiration, it popped into our heads, and that was it. But I think it’s also because, to be perfectly honest, we both were a little bit annoyed by the way people throw the word “literally” around when they really mean “figuratively.” To be able to say we’re quite literally books felt super satisfying. That’s what we are.

We also have tote bags, but that’s it for swag. You have to carry books, and the bags were actually designed to carry books.

Is there anything that we haven’t covered that you would like to bring attention to about your books?

LC: I think one thing that we should mention is the fact that these books were written in another time. In many of the ones that we have read—and certainly this will be true in some of the ones that we choose to republish—there are social sensibilities and racial depictions that are rightly objectionable to the modern reader. We go through a process with each book of deciding whether or not the presence of that sensibility—because to a certain extent, it’s pretty unavoidable—is going to make that a book we still believe in enough that we’ll still bring it to light, or is it one that just needs to stay shelved? It’s a very difficult process to engage in. I think that the reason why we think it’s important to reprint books that may contain those things regardless, is because it’s an important part of our history that we’re doing a disservice to if we pretend like it doesn’t exist. We feel like these are conversations that we need to be engaging in. You need to sit in the discomfort of it. The fact that it’s jarring when you encounter the N-word in a text is a good thing. That tension point is a really great place to have a conversation—not to whitewash it and remove it, not to cancel an author completely. This is a part of our past, and it certainly influences where we are today. I would argue, and Bremond agrees, that we need to be having these conversations now more than ever, and a book is a good place to start.

There are a lot of people who feel like they don’t have standing in that conversation, but if you read a book about it, then you can have an opinion about it. You can voice a perspective. It maybe opens the door for more honest conversations. We trust that our readers are able to do that, that they’re able to understand the nuance and have conversations and engage with one another in a way that is thoughtful and intentional and respectful.

And finally, can you talk about what role the library has played in your life?

LC: Oh, yes, I would love to talk about that. (laughs) So the Austin Public Library in the 70s was the most glorious place to spend a Saturday morning. First of all, the building is beautiful. This is the old Austin Public Library I’m talking about. I used to go there every single Saturday. My dad would drop me off. I got my first library card there, and it was paper. You had to be able to write your name in order to get a card, and I had just learned how to do because I was in kindergarten. This notion that you could take books home for free was so mind blowing to me. My dad made this rule that I could only take home as many as I could carry. I devised all kinds of crazy ways to hold more and more books. The librarians there were amazing. They were so great. They would do things like set books aside for me that they thought I would like, or they would have a new book that I would read and tell them what I thought of it. I mean, those librarians made me feel so good about myself as a reader.

BBM: The children’s section was downstairs, and we’ve talked about how we both have a memory of that staircase and going down into the cool of the basement. It was also where the LPs were. You could check out albums, I think you can even check out art. It was an amazing place. And of course, my grandmother worked in the public library, and so that was really cool. She worked nights and weekends, so I didn’t usually see her, but when I did, it was like, “Wow. My grandmother has the run of this whole place.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tags: bremond berry macdougall, lisa cooper, quite literally books